Western canon

This article possibly contains original research. (December 2021) |

The Western canon is the embodiment of high-culture literature, music, philosophy, and works of art that are highly cherished across the Western hemisphere, such works having achieved the status of classics.

Recent discussions upon the matter emphasise cultural diversity within the canon.[1][2] The canons of music and visual arts have been broadened to encompass often overlooked periods, whilst recent media like cinema grapple with a precarious position. Criticism arises, with some viewing changes as prioritising activism over aesthetic values, often associated with critical theory, as well as postmodernism.[3] Another critique highlights a narrow interpretation of the West, dominated by British and American culture, at least under contemporary circumstances, prompting demands for a more diversified canon amongst the hemisphere.[3]

Literary canon

[edit]Classic book

[edit]

A classic is a book, or any other work of art, accepted as being exemplary or noteworthy. In the second-century Roman miscellany Attic Nights, Aulus Gellius refers to writers as "classicus... scriptor, non proletarius" ("A distinguished, not a commonplace writer").[4] Such classification were initiated with the Greeks' ranking their cultural works, with the word canon (ancient Greek κανών, kanṓn: "measuring rod, standard").[5] Similarly, early Christian Church Fathers declared as canon the authoritative texts of the New Testament, preserving them given the expense of vellum and papyrus and mechanical book reproduction. Thus, being included in a canon ensured a book's preservation as the best way to retain information about a civilization. In contemporary use, the Western canon defines the best of Western culture. In the ancient world, at the Alexandrian Library, scholars coined the Greek term Hoi enkrithentes ["the admitted", "the included"] to identify the writers in the canon. Although the term is often associated with the Western canon, it can be applied to works of literature, music and art, etc. from all traditions, such as the Chinese classics.

With regard to books, what makes a book "classic" has concerned various authors, from Mark Twain to Italo Calvino, and questions such as "Why Read the Classics?", and "What Is a Classic?" have been considered by others, including T. S. Eliot, Charles Augustin Sainte-Beuve, Michael Dirda, and Ezra Pound.

The terms "classic book" and Western canon are closely related concepts, but are not necessarily synonymous. A "canon" is a list of books considered to be "essential", and it can be published as a collection (such as Great Books of the Western World, Modern Library, Everyman's Library or Penguin Classics), presented as a list with an academic's imprimatur (such as Harold Bloom's[6]), or be the official reading list of a university. In The Western Canon Bloom lists "the major Western writers" as Dante Alighieri, Geoffrey Chaucer, Miguel de Cervantes, Michel de Montaigne, William Shakespeare, Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, William Wordsworth, Charles Dickens, Leo Tolstoy, James Joyce and Marcel Proust.

Great Books Program

[edit]

A university or college Great Books Program is a program inspired by the Great Books movement begun in the United States in the 1920s by John Erskine of Columbia University, which proposed to improve the higher education system by returning it to the western liberal arts tradition of broad cross-disciplinary learning. These academics and educators included Robert Hutchins, Mortimer Adler, Stringfellow Barr, Scott Buchanan, Jacques Barzun, and Alexander Meiklejohn. The view among them was that the emphasis on narrow specialization in American colleges had harmed the quality of higher education by failing to expose students to the important products of Western civilization and thought.

The essential component of such programs is a high degree of engagement with primary texts, called the Great Books. The curricula of Great Books programs often follow a canon of texts considered more or less essential to a student's education, such as Plato's Republic, or Dante's Divine Comedy. Such programs often focus exclusively on Western culture. Their employment of primary texts dictates an interdisciplinary approach, as most of the Great Books do not fall neatly under the prerogative of a single contemporary academic discipline. Great Books programs often include designated discussion groups as well as lectures, and have small class sizes. In general students in such programs receive an abnormally high degree of attention from their professors, as part of the overall aim of fostering a community of learning.

Over 100 institutions of higher learning, mostly in the United States, offer some version of a Great Books Program as an option for students.[7]

For much of the 20th century, the Modern Library provided a larger convenient list of the Western canon.[8] The list numbered more than 300 items by the 1950s, by authors from Aristotle to Albert Camus, and has continued to grow. When in the 1990s the concept of the Western canon was vehemently condemned, just as earlier Modern Library lists had been criticized as "too American," Modern Library responded by preparing new lists of "100 Best Novels" and "100 Best Nonfiction" compiled by famous writers, and later compiled lists nominated by book purchasers and readers.[9]

Debate

[edit]Some intellectuals have championed a "high conservative modernism" that insists that universal truths exist, and have opposed approaches that deny the existence of universal truths.[10] Yale University Professor of Humanities and famous literary critic Harold Bloom also argued strongly in favor of the canon, in his 1994 book The Western Canon: The Books and School of the Ages, and in general the canon remains as a represented idea in many institutions.[11] Allan Bloom (no relation), in his highly influential The Closing of the American Mind: How Higher Education Has Failed Democracy and Impoverished the Souls of Today's Students (1987), argues that moral degradation results from ignorance of the great classics that shaped Western culture. Bloom further comments: "But one thing is certain: wherever the Great Books make up a central part of the curriculum, the students are excited and satisfied."[12] His book was widely cited by some intellectuals for its argument that the classics contained universal truths and timeless values which were being ignored by cultural relativists.[13][14]

Classicist Bernard Knox made direct reference to this topic when he delivered his 1992 Jefferson Lecture (the U.S. federal government's highest honor for achievement in the humanities).[15] Knox used the intentionally "provocative" title "The Oldest Dead White European Males"[16] as the title of his lecture and his subsequent book of the same name, in both of which Knox defended the continuing relevance of classical culture to modern society.[17][18]

Defenders maintain that those who undermine the canon do so out of primarily political interests, and that such criticisms are misguided and/or disingenuous. As John Searle, Professor of Philosophy at the University of California, Berkeley, has written:

There is a certain irony in this [i.e., politicized objections to the canon] in that earlier student generations, my own for example, found the critical tradition that runs from Socrates through the Federalist Papers, through the writings of Mill and Marx, down to the twentieth century, to be liberating from the stuffy conventions of traditional American politics and pieties. Precisely by inculcating a critical attitude, the "canon" served to demythologize the conventional pieties of the American bourgeoisie and provided the student with a perspective from which to critically analyze American culture and institutions. Ironically, the same tradition is now regarded as oppressive. The texts once served an unmasking function; now we are told that it is the texts which must be unmasked.[11]

One of the main objections to a canon of literature is the question of authority; who should have the power to determine what works are worth reading?

Charles Altieri, of the University of California, Berkeley, states that canons are "an institutional form for exposing people to a range of idealized attitudes." It is according to this notion that work may be removed from the canon over time to reflect the contextual relevance and thoughts of society.[19] American historian Todd M. Compton argues that canons are always communal in nature; that there are limited canons for, say a literature survey class, or an English department reading list, but there is no such thing as one absolute canon of literature. Instead, there are many conflicting canons. He regards Bloom's "Western Canon" as a personal canon only.[20]

The process of defining the boundaries of the canon is endless. The philosopher John Searle has said, "In my experience there never was, in fact, a fixed 'canon'; there was rather a certain set of tentative judgments about what had importance and quality. Such judgments are always subject to revision, and in fact they were constantly being revised."[11] One of the notable attempts at compiling an authoritative canon for literature in the English-speaking world was the Great Books of the Western World program. This program, developed in the middle third of the 20th century, grew out of the curriculum at the University of Chicago. University president Robert Maynard Hutchins and his collaborator Mortimer Adler developed a program that offered reading lists, books, and organizational strategies for reading clubs to the general public.[21][22][23] An earlier attempt had been made in 1909 by Harvard University president Charles W. Eliot, with the Harvard Classics, a 51-volume anthology of classic works from world literature. Eliot's view was the same as that of Scottish philosopher and historian Thomas Carlyle: "The true University of these days is a Collection of Books". ("The Hero as Man of Letters", 1840)

In the English-speaking world

[edit]British renaissance poetry

[edit]The canon of Renaissance English poetry of the 16th and early 17th century has always been in some form of flux and towards the end of the 20th century the established canon was criticised, especially by those who wished to expand it to include, for example, more women writers.[24] However, the central figures of the British renaissance canon remain, Edmund Spenser, Sir Philip Sidney, Christopher Marlowe, William Shakespeare, Ben Jonson, and John Donne.[25] Spenser, Donne, and Jonson were major influences on 17th-century poetry. However, poet John Dryden condemned aspects of the metaphysical poets in his criticism. In the 18th century Metaphysical poetry fell into further disrepute,[26] while the interest in Elizabethan poetry was rekindled through the scholarship of Thomas Warton and others. However, the canon of Renaissance poetry was formed in the Victorian period with anthologies like Palgrave's Golden Treasury.[27]

In the twentieth century T. S. Eliot and Yvor Winters were two literary critics who were especially concerned with revising the canon of renaissance English literature. Eliot, for example, championed poet Sir John Davies in an article in The Times Literary Supplement in 1926. During the course of the 1920s, Eliot did much to establish the importance of the metaphysical school, both through his critical writing and by applying their method in his own work. However, by 1961 A. Alvarez was commenting that "it may perhaps be a little late in the day to be writing about the Metaphysicals. The great vogue for Donne passed with the passing of the Anglo-American experimental movement in modern poetry."[28] Two decades later, a hostile view was expressed that emphasis on their importance had been an attempt by Eliot and his followers to impose a 'high Anglican and royalist literary history' on 17th-century English poetry.[29]

The American critic Yvor Winters suggested in 1939 an alternative canon of Elizabethan poetry,[30] which would exclude the famous representatives of the Petrarchan school of poetry, represented by Sir Philip Sidney and Edmund Spenser. Winters claimed that the Native or Plain Style anti-Petrarchan movement had been undervalued and argued that George Gascoigne (1525–1577) "deserves to be ranked […] among the six or seven greatest lyric poets of the century, and perhaps higher".[31]

Towards the end of the 20th century the established canon was increasingly disputed.[24]

Expansion of the literary canon in the 20th century

[edit]In the twentieth century there was a general reassessment of the literary canon, including women's writing, post-colonial literatures, gay and lesbian literature, writing by racialized minorities, working people's writing, and the cultural productions of historically marginalized groups. This reassessment has resulted in a whole scale expansion of what is considered "literature", and genres hitherto not regarded as "literary", such as children's writing, journals, letters, travel writing, and many others are now the subjects of scholarly interest.[32][33][34]

The Western literary canon has also expanded to include the literature of Asia, Africa, the Middle East, and South America. Writers from Africa, Turkey, China, Egypt, Peru, and Colombia, Japan, etc., have received Nobel prizes since the late 1960s. Writers from Asia and Africa have also been nominated for, and also won, the Booker prize in recent years.

Feminism and the literary canon

[edit]

Susan Hardy Aitken argues that the Western canon has maintained itself by excluding and marginalising women, whilst idealising the works of European men.[35] Where women's work is introduced it can be considered inappropriately rather than recognising the importance of their work; a work's greatness is judged against socially situated factors which exclude women, whilst being portrayed as an intellectual approach.[36]

The feminist movement produced both feminist fiction and non-fiction and created new interest in women's writing. It also prompted a general reevaluation of women's historical and academic contributions in response to the belief that women's lives and contributions have been underrepresented as areas of scholarly interest.[32]

However, in Britain and America at least women achieved major literary success from the late eighteenth century, and many major nineteenth-century British novelists were women, including Jane Austen, the Brontë family, Elizabeth Gaskell, and George Eliot. There were also three major female poets, Elizabeth Barrett Browning,[37] Christina Rossetti and Emily Dickinson.[38][39] In the twentieth century there were also many major female writers, including Katherine Mansfield, Dorothy Richardson, Virginia Woolf, Eudora Welty, and Marianne Moore. Notable female writers in France include Colette, Simone de Beauvoir, Marguerite Yourcenar, Nathalie Sarraute, Marguerite Duras and Françoise Sagan.

Much of the early period of feminist literary scholarship was given over to the rediscovery and reclamation of texts written by women. Virago Press began to publish its large list of 19th and early 20th-century novels in 1975 and became one of the first commercial presses to join in the project of reclamation.

African and Afro-American authors

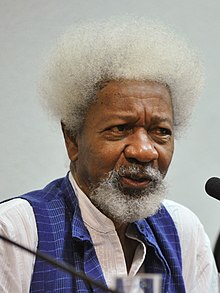

[edit]In the twentieth century, the Western literary canon started to include African writers not only from African-American writers, but also from the wider African diaspora of writers in Britain, France, Latin America, and Africa. This correlated largely with the shift in social and political views during the civil rights movement in the United States. The first global recognition came in 1950 when Gwendolyn Brooks was the first African American to win a Pulitzer Prize for Literature. Chinua Achebe's novel Things Fall Apart helped draw attention to African literature. Nigerian Wole Soyinka was the first African to win the Nobel Prize in Literature, in 1986, and American Toni Morrison was the first African-American woman to win, in 1993.

Some early Afro-American writers were inspired to defy ubiquitous racial prejudice by proving themselves equal to European American authors. As Henry Louis Gates Jr., has said, "it is fair to describe the subtext of the history of black letters as this urge to refute the claim that because blacks had no written traditions they were bearers of an inferior culture."[40]

African-American writers were also attempting to subvert the literary and power traditions of the United States. Some scholars assert that writing has traditionally been seen as "something defined by the dominant culture as a white male activity."[40] This means that, in American society, literary acceptance has traditionally been intimately tied in with the very power dynamics which perpetrated such evils as racial discrimination. By borrowing from and incorporating the non-written oral traditions and folk life of the African diaspora, African-American literature broke "the mystique of connection between literary authority and patriarchal power."[41] In producing their own literature, African Americans were able to establish their own literary traditions devoid of the European intellectual filter. This view of African-American literature as a tool in the struggle for African-American political and cultural liberation has been stated for decades, most famously by W. E. B. Du Bois.[42]

Asia and North Africa

[edit]Since the 1960s the Western literary canon has been expanded to include writers from Asia, Africa, and the Middle East.[43] This is reflected in the Nobel Prizes awarded in literature.[44]

Yasunari Kawabata (1899–1972)[45] was a Japanese novelist and short story writer whose spare, lyrical, subtly-shaded prose works won him the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1968, the first Japanese author to receive the award. His works have enjoyed broad international appeal and are still widely read.

Naguib Mahfouz (1911–2006) was an Egyptian writer who won the 1988 Nobel Prize for Literature. He is regarded as one of the first contemporary writers of Arabic literature, along with Tawfiq el-Hakim, to explore themes of existentialism.[46] He published 34 novels, over 350 short stories, dozens of movie scripts, and five plays over a 70-year career. Many of his works have been made into Egyptian and foreign films.

Kenzaburō Ōe (1935–2023) was a Japanese writer and a major figure in contemporary Japanese literature. His novels, short stories, and essays, strongly influenced by French and American literature and literary theory, deal with political, social, and philosophical issues, including nuclear weapons, nuclear power, social non-conformism, and existentialism. Ōe was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1994 for creating "an imagined world, where life and myth condense to form a disconcerting picture of the human predicament today".[47]

Guan Moye (b. 1955), better known by the pen name "Mo Yan", is a Chinese novelist and short story writer. Donald Morrison of the U.S. news magazine TIME referred to him as "one of the most famous, oft-banned and widely pirated of all Chinese writers",[48] and Jim Leach called him the Chinese answer to Franz Kafka or Joseph Heller.[49] He is best known to Western readers for his 1987 novel Red Sorghum Clan, of which the Red Sorghum and Sorghum Wine volumes were later adapted for the film Red Sorghum. In 2012, Mo was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature for his work as a writer "who with hallucinatory realism merges folk tales, history and the contemporary".[50][51]

Orhan Pamuk (b. 1952) is a Turkish novelist, screenwriter, academic, and recipient of the 2006 Nobel Prize in Literature. One of Turkey's most prominent novelists,[52] his books have sold over thirteen million copies in sixty-three languages,[53] making him the country's best-selling writer.[54] Pamuk is the author of novels including The White Castle, The Black Book, The New Life, My Name Is Red, Snow, The Museum of Innocence, and A Strangeness in My Mind. He is the Robert Yik-Fong Tam Professor in the Humanities at Columbia University, where he teaches writing and comparative literature. Born in Istanbul,[55] Pamuk is the first Turkish Nobel laureate. He is also the recipient of numerous other literary awards. My Name Is Red won the 2002 Prix du Meilleur Livre Étranger, 2002 Premio Grinzane Cavour, and 2003 International Dublin Literary Award.

Latin America

[edit]

Octavio Paz Lozano (1914–1998) was a Mexican poet and diplomat. For his body of work, he was awarded the 1981 Miguel de Cervantes Prize, the 1982 Neustadt International Prize for Literature, and the 1990 Nobel Prize in Literature.

Gabriel García Márquez[56] (1927–2014) was a Colombian novelist, short-story writer, screenwriter, and journalist. Considered one of the most significant authors of the 20th century and one of the best in the Spanish language, he was awarded the 1972 Neustadt International Prize for Literature and the 1982 Nobel Prize in Literature.[57]

García Márquez started as a journalist, and wrote many acclaimed non-fiction works and short stories, but is best known for his novels, such as One Hundred Years of Solitude (1967), The Autumn of the Patriarch (1975), and Love in the Time of Cholera (1985). His works have achieved significant critical acclaim and widespread commercial success, most notably for popularizing a literary style labeled as magic realism, which uses magical elements and events in otherwise ordinary and realistic situations. Some of his works are set in a fictional village called Macondo (the town mainly inspired by his birthplace Aracataca), and most of them explore the theme of solitude. On his death in April 2014, Juan Manuel Santos, the President of Colombia, described him as "the greatest Colombian who ever lived."[58]

Mario Vargas Llosa, (b. 1936)[59] is a Peruvian writer, politician, journalist, essayist, college professor, and recipient of the 2010 Nobel Prize in Literature.[60] Vargas Llosa is one of Latin America's most significant novelists and essayists, and one of the leading writers of his generation. Some critics consider him to have had a larger international impact and worldwide audience than any other writer of the Latin American Boom.[61] Upon announcing the 2010 Nobel Prize in Literature, the Swedish Academy said it had been given to Vargas Llosa "for his cartography of structures of power and his trenchant images of the individual's resistance, revolt, and defeat".[62]

Canon of philosophers

[edit]This article's factual accuracy is disputed. (December 2021) |

Many philosophers today agree that Greek philosophy has influenced much of Western culture since its inception. Alfred North Whitehead once noted: "The safest general characterization of the European philosophical tradition is that it consists of a series of footnotes to Plato."[63] Clear, unbroken lines of influence lead from ancient Greek and Hellenistic philosophers to Early Islamic philosophy, the European Renaissance, and the Age of Enlightenment.[64]

Plato was a philosopher in Classical Greece and the founder of the Academy in Athens. He is widely considered the most pivotal figure in the development of philosophy, especially the Western tradition.[65][66]

Aristotle was an ancient Greek philosopher. His writings cover many subjects – including physics, biology, zoology, metaphysics, logic, ethics, aesthetics, rhetoric, linguistics, politics and government—and constitute the first comprehensive system of Western philosophy.[67] Aristotle's views on physical science had a profound influence on medieval scholarship. Their influence extended from Late Antiquity into the Renaissance, and his views were not replaced systematically until the Enlightenment and theories such as classical mechanics. In metaphysics, Aristotelianism profoundly influenced Judeo-Islamic philosophical and theological thought during the Middle Ages and continues to influence Christian theology, especially the Neoplatonism of the Early Church and the scholastic tradition of the Roman Catholic Church. Aristotle was well known among medieval Muslim intellectuals and revered as "The First Teacher" (Arabic: المعلم الأول). His ethics, though always influential, gained renewed interest with the modern advent of virtue ethics.

Boethius' On the Consolation of Philosophy (Latin: De consolatione philosophiae) is often acclaimed as a central work from Late Antiquity, at the cusp of the early medieval period, that remained influential throughout the Middle Ages. Of Boethius, it has been said that "[along] with Augustine and Aristotle, he is the fundamental philosophical and theological author in the Latin tradition";[68] Edward Gibbon wrote of the Consolatione that it is "a golden volume not unworthy of the leisure of Plato or Tully",[69] and Bertrand Russell wrote that, by merit of the same, Boethius "would have been remarkable in any age; in the age in which he lived he is utterly amazing."[70]

The vast body of Christian philosophy is typically represented on reading lists mainly by Augustine of Hippo and Thomas Aquinas. The academic canon of early modern philosophy generally includes Descartes, Spinoza, Leibniz, Locke, Berkeley, Hume, and Kant.[71]

Renaissance philosophy

[edit]Major philosophers of the Renaissance include Niccolò Machiavelli, Michel de Montaigne, Pico della Mirandola, Nicholas of Cusa and Giordano Bruno, Marsilio Ficino[72] and Gemistos Plethon.[73]

Seventeenth-century philosophers

[edit]

The seventeenth century was important for philosophy, and the major figures were Francis Bacon, Thomas Hobbes, René Descartes, Blaise Pascal, Baruch Spinoza, John Locke and Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz.[74]

Eighteenth-century philosophers

[edit]Major philosophers of the eighteenth century include George Berkeley, Montesquieu, Voltaire, David Hume, Giambattista Vico,[75] Jean-Jacques Rousseau, Denis Diderot, Immanuel Kant, Edmund Burke and Jeremy Bentham.[74]

Nineteenth-century philosophers

[edit]Important nineteenth century philosophers include Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel (1770–1831),Giuseppe Mazzini,[76] Arthur Schopenhauer, Auguste Comte, Søren Kierkegaard, Karl Marx, Friedrich Engels and Friedrich Nietzsche.

Twentieth-century philosophers

[edit]Major twentieth century figures include Henri Bergson, Edmund Husserl, Bertrand Russell, Martin Heidegger, Ludwig Wittgenstein and Jean-Paul Sartre, Simone de Beauvoir, and Simone Weil, Michel Foucault, Pierre Bourdieu, Jacques Derrida and Jürgen Habermas. A porous distinction between analytic and continental approaches emerged during this period.

Music

[edit]

Classical music forms the core of canon music and remains mostly unchanged to our days. It integrates a huge body of works starting from the 17th century and are reproduced on an ensemble of all acoustic musical instruments that were common in that century's Europe.

The term "classical music" did not appear until the early 19th century, in an attempt to distinctly canonize the period from Johann Sebastian Bach to Ludwig van Beethoven as a golden age. In addition to Bach and Beethoven, the other major figures from this period were George Frideric Handel, Joseph Haydn and Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart.[77] The earliest reference to "classical music" recorded by the Oxford English Dictionary is from about 1836.[78]

In classical music, during the nineteenth century a "canon" developed which focused on what was felt to be the most important works written since 1600, with a great concentration on the later part of this period, termed the Classical period, which is generally taken to begin around 1750. After Beethoven, the major nineteenth-century composers include Franz Schubert, Robert Schumann, Frédéric Chopin, Hector Berlioz, Franz Liszt, Richard Wagner, Johannes Brahms, Anton Bruckner, Giuseppe Verdi, Gustav Mahler, and Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky.[79]

In the 2000s, the standard concert repertoire of professional orchestras, chamber music groups, and choirs tends to focus on works by a relatively small number of mainly 18th- and 19th-century male composers. Many of the works deemed to be part of the musical canon are from genres regarded as the most serious, such as the symphony, concerto, string quartet, and opera. Folk music was already giving art music melodies, and from the late 19th century, in an atmosphere of increasing nationalism, folk music began to influence composers in formal and other ways, before being admitted to some sort of status in the canon itself.

Since the early twentieth century non-Western music has begun to influence Western composers. In particular, direct homages to Javanese gamelan music are found in works for western instruments by Claude Debussy, Béla Bartók, Francis Poulenc, Olivier Messiaen, Pierre Boulez, Benjamin Britten, John Cage, Steve Reich, and Philip Glass.[80] Debussy was immensely interested in non-Western music and its approaches to composition. Specifically, he was drawn to the Javanese gamelan,[81] which he first heard at the 1889 Paris Exposition. He was not interested in directly quoting his non-Western influences, but instead allowed this non-Western aesthetic to generally influence his own musical work, for example, by frequently using quiet, unresolved dissonances, coupled with the damper pedal, to emulate the "shimmering" effect created by a gamelan ensemble. American composer Philip Glass was not only influenced by the eminent French composition teacher Nadia Boulanger,[82] but also by the Indian musicians Ravi Shankar and Alla Rakha, His distinctive style arose from his work with Shankar and Rakha and their perception of rhythm in Indian music as being entirely additive.[83]

In the latter half of the 20th century the canon expanded to cover the so-called Early music of the pre-classical period, and Baroque music by composers other than Bach and George Frideric Handel, including Antonio Vivaldi, Claudio Monteverdi, Domenico Scarlatti, Alessandro Scarlatti, Henry Purcell, Georg Philipp Telemann, Jean-Baptiste Lully, Jean-Philippe Rameau, Marc-Antoine Charpentier, Arcangelo Corelli, François Couperin, Heinrich Schütz, and Dieterich Buxtehude. Earlier composers, such as Giovanni Pierluigi da Palestrina, Orlande de Lassus and William Byrd, have also received more attention in the last hundred years.[84]

The absence of women composers from the classical canon was brought to the forefront of musicological literature in the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries. Even though many women composers have written music in the common practice period and beyond, their works remain extremely underrepresented in concert programs, music history curriculums, and music anthologies. In particular, musicologist Marcia J Citron has examined "the practices and attitudes that have led to the exclusion of women composers from the received 'canon' of performed musical works."[85] Since around 1980 the music of Hildegard von Bingen (1098–1179), a German Benedictine abbess, and Finnish composer Kaija Saariaho (born 1952) has begun to enter the canon. Saariaho's opera L'amour de loin has been staged in some of the world's major opera houses, including The English National Opera (2009)[86] and in 2016 the Metropolitan Opera in New York.

The classical ensemble canon very rarely integrates musical instruments that are not acoustic and of western origins, it stayed apart from the wide use of electric, electronic and digital instruments that are common in today's popular music.

Visual arts

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (June 2018) |

The backbone of traditional Western art history are artworks commissioned by wealthy patrons for private or public enjoyment. Much of this was religious art, mostly Roman Catholic art. The classical art of Greece and Rome has, since the Renaissance, been the fount of the Western tradition.

Giorgio Vasari (1511–1574) is the originator of the artistic canon and the originator of many of the concepts it embodies. His Lives of the Most Excellent Painters, Sculptors, and Architects covers only artists working in Italy,[87] with a strong pro-Florentine prejudice, and has cast a long shadow over succeeding centuries. Northern European art has arguably never quite caught up to Italy in terms of prestige, and Vasari's placing of Giotto as the founding father of "modern" painting has largely been retained. In painting, the rather vague term of Old master covers painters up to about the time of Goya.

This "canon" remains prominent, as indicated by the selection present in art history textbooks, as well as the prices obtained in the art trade. But there have been considerable swings in what is valued. In the 19th century the Baroque fell into great disfavour, but it was revived from around the 1920s, by which time the art of the 18th and 19th century was largely disregarded. The High Renaissance, which Vasari regarded as the greatest period, has always retained its prestige, including works by Leonardo da Vinci, Michelangelo, and Raphael, but the succeeding period of Mannerism has fallen in and out of favour.

In the 19th century the beginnings of academic art history, led by German universities, led to much better understanding and appreciation of medieval art, and a more nuanced understanding of classical art, including the realization that many if not most treasured masterpieces of sculpture were late Roman copies rather than Greek originals. The European tradition of art was expanded to include Byzantine art and the new discoveries of archaeology, notably Etruscan art, Celtic art and Upper Paleolithic art.

Since the 20th century there has been an effort to re-define the discipline to be more inclusive of art made by women; vernacular creativity, especially in printed media; and an expansion to include works in the Western tradition produced outside Europe. At the same time there has been a much greater appreciation of non-Western traditions, including their place with Western art in wider global or Eurasian traditions. The decorative arts have traditionally had a much lower critical status than fine art, although often highly valued by collectors, and still tend to be given little prominence in undergraduate studies or popular coverage on television and in print.

Women and art

[edit]

English artist and sculptor Barbara Hepworth DBE (1903 – 1975), whose work exemplifies Modernism, and in particular modern sculpture, is one of the few female artists to achieve international prominence.[88] In 2016 the art of American modernist Georgia O'Keeffe has been staged at the Tate Modern, in London, and is then moving in December 2016 to Vienna, Austria, before visiting the Art Gallery of Ontario, Canada in 2017.[89]

Historical exclusion of women

[edit]Women were discriminated against in terms of obtaining the training necessary to be an artist in the mainstream Western traditions. In addition, since the Renaissance the nude, more often than not female,[citation needed] has had a special position as subject matter. In her 1971 essay, "Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists?", Linda Nochlin analyzes what she sees as the embedded privilege in the predominantly male Western art world and argues that women's outsider status allowed them a unique viewpoint to not only critique women's position in art, but to additionally examine the discipline's underlying assumptions about gender and ability.[90] Nochlin's essay develops the argument that both formal and social education restricted artistic development to men, preventing women (with rare exception) from honing their talents and gaining entry into the art world.[90]

In the 1970s, feminist art criticism continued this critique of the institutionalized sexism of art history, art museums, and galleries, and questioned which genres of art were deemed museum-worthy.[91] This position is articulated by artist Judy Chicago: "[I]t is crucial to understand that one of the ways in which the importance of male experience is conveyed is through the art objects that are exhibited and preserved in our museums. Whereas men experience presence in our art institutions, women experience primarily absence, except in images that do not necessarily reflect women's own sense of themselves."[92]

Sources containing canonical lists

[edit]

Top row: Antonio Vivaldi, Johann Sebastian Bach, George Frideric Handel, Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, Ludwig van Beethoven

second row: Gioachino Rossini, Felix Mendelssohn, Frédéric Chopin, Richard Wagner, Giuseppe Verdi

third row: Johann Strauss II, Johannes Brahms, Georges Bizet, Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky, Antonín Dvořák

bottom row: Edvard Grieg, Edward Elgar, Sergei Rachmaninoff, George Gershwin, Aram Khachaturian

English literature

[edit]- Modern Library 100 Best Novels – English-language novels of the 20th century

- Library of America, classic American literature

International literature

[edit]- Bibliothèque de la Pléiade[93]

- Everyman's Library (Modern works)

- Great Books of the Western World

- História da Literatura Ocidental (in Portuguese) by Otto Maria Carpeaux

- Le Monde's 100 Books of the Century – books of the 20th century

- Modern Library

- Oxford World's Classics

- Penguin Classics

- John Cowper Powys: One Hundred Best Books (1916)[94]

- Verso Books' Radical Thinkers

- ZEIT-Bibliothek der 100 Bücher – Die Zeit list of 100 books

American and Canadian university reading lists

[edit]- Brigham Young University's Honors Program's Great Works List[95]

- Bard College's Language & Thinking program, a series of seminars on great books taken on by all incoming freshmen[96]

- St. John's College Great Books reading list (established by Scott Buchanan and Stringfellow Barr)

- Baylor University's Great Texts Reading List[97]

- The Harvard Classics

Contemporary anthologies of renaissance literature

[edit]The preface to the Blackwell anthology of Renaissance Literature from 2003 acknowledges the importance of online access to literary texts on the selection of what to include, meaning that the selection can be made on basis of functionality rather than representativity".[98] This anthology has made its selection based on three principles. One is "unabashedly canonical", meaning that Sidney, Spenser, Marlowe, Shakespeare, and Jonson have been given the space prospective users would expect. A second principle is "non-canonical", giving female writers such as Anne Askew, Elizabeth Cary, Emilia Lanier, Martha Moulsworth, and Lady Mary Wroth a representative selection. It also includes texts that may not be representative of the qualitatively best efforts of Renaissance literature, but of the quantitatively most numerous texts, such as homilies and erotica. A third principle has been thematic, so that the anthology aims to include texts that shed light on issues of special interest to contemporary scholars.

The Blackwell anthology is still firmly organised around authors, however. A different strategy has been observed by The Penguin Book of Renaissance Verse from 1992.[99] Here the texts are organised according to topic, under the headings The Public World, Images of Love, Topographies, Friends, Patrons and the Good Life, Church, State and Belief, Elegy and Epitaph, Translation, Writer, Language and Public. It is arguable that such an approach is more suitable for the interested reader than for the student. While the two anthologies are not directly comparable, since the Blackwell anthology also includes prose and the Penguin anthology goes up to 1659, it is telling that while the larger Blackwell anthology contains work by 48 poets, seven of which are women, the Penguin anthology contains 374 poems by 109 poets, including 13 women and one poet each in Welsh, Siôn Phylip, and Irish, Eochaidh Ó Heóghusa.

German literature

[edit]Best German Novels of the Twentieth Century

[edit]The Best German Novels of the Twentieth Century is a list of books compiled in 1999 by Literaturhaus München and Bertelsmann, in which 99 prominent German authors, literary critics, and scholars of German ranked the most significant German-language novels of the twentieth century.[100] The group brought together 23 experts from each of the three categories.[101] Each was allowed to name three books as having been the most important of the century. Cited by the group were five titles by both Franz Kafka and Arno Schmidt, four by Robert Walser, and three by Thomas Mann, Hermann Broch, Anna Seghers, and Joseph Roth.[100]

Der Kanon, edited by Marcel Reich-Ranicki, is a large anthology of exemplary works of German literature.[102]

French literature

[edit]See key texts of French literature

Canon of Dutch Literature

[edit]The Canon of Dutch Literature comprises a list of 1000 works of Dutch-language literature important to the cultural heritage of the Low Countries, and is published on the DBNL. Several of these works are lists themselves; such as early dictionaries, lists of songs, recipes, biographies, or encyclopedic compilations of information such as mathematical, scientific, medical, or plant reference books. Other items include early translations of literature from other countries, history books, first-hand diaries, and published correspondence. Notable original works can be found by author name.

Scandinavia

[edit]Danish Culture Canon

[edit]The Danish Culture Canon consists of 108 works of cultural excellence in eight categories: architecture, visual arts, design and crafts, film, literature, music, performing arts, and children's culture. An initiative of Brian Mikkelsen in 2004, it was developed by a series of committees under the auspices of the Danish Ministry of Culture in 2006–2007 as "a collection and presentation of the greatest, most important works of Denmark's cultural heritage." Each category contains 12 works, although music contains 12 works of score music and 12 of popular music, and the literature section's 12th item is an anthology of 24 works.[103][104]

Sweden

[edit]Världsbiblioteket (The World Library) was a Swedish list of the 100 best books in the world, created in 1991 by the Swedish literary magazine Tidningen Boken. The list was compiled through votes from members of the Svenska Akademien, Swedish Crime Writers' Academy, librarians, authors, and others. Approximately 30 of the books were Swedish.

Norway

[edit]Spain

[edit]For the Spanish culture, specially for the Spanish literature, during the 19th and the first third of the 20th century similar lists were created trying to define the literary canon. This canon was established mainly through teaching programs, and literary critics like Pedro Estala, Antonio Gil y Zárate, Marcelino Menéndez Pelayo, Ramón Menéndez Pidal, or Juan Bautista Bergua. In the last decades, other important critics have been contributing to the topic, among them, Fernando Lázaro Carreter, José Manuel Blecua Perdices, Francisco Rico, and José Carlos Mainer.

Other Spanish languages have also their own literary canons. A good introduction to the Catalan literary canon is La invenció de la tradició literària by Manel Ollé, from the Open University of Catalonia.[105]

- Biblioteca de Autores Españoles, BAE (Manuel Rivadeneyra, Buenaventura Carlos Aribau, 1846–1888)

- Nueva Biblioteca de Autores Españoles (Marcelino Menéndez y Pelayo, ed. Bailly-Baillière, 1905–1918); the same author selected Las cien mejores poesías de la lengua castellana, Victoriano Suárez, 1908[106]

- Clásicos Castellanos (Ramón Menéndez Pidal, Centro de Estudios Históricos, eds. La Lectura, and Espasa Calpe, 1910–1935)[107]

- Las mil mejores poesías de la lengua castellana (Juan Bautista Bergua)

- Mil libros (Luis Nueda, Antonio Espina, since 1940 —not limited to the books in Spanish—)

- Floresta de la lírica española (José Manuel Blecua Teijeiro, Antología Hispánica, Gredos, 1957)

- Centro Virtual Cervantes (Instituto Cervantes, online, since 1997)

- Biblioteca Clásica (Francisco Rico, Real Academia Española, Círculo de Lectores, 2011)

- Les millors obres de la literatura catalana (Joaquim Molas, Edicions 62, and La Caixa)

See also

[edit]- Africana philosophy – Area of study within Africana studies

- Artistic canons of body proportions – Criteria used in formal figurative art

- Atlantic Canada's 100 Greatest Books

- Catalogue raisonné – Comprehensive, annotated listing of all the known artworks by an artist

- Censorship – Suppression of speech or other information

- Chinese classics – Classic texts of Chinese literature

- Chinese philosophy – Type of philosophy

- Great Conversation – Concept in the philosophy of literature

- Indian literature

- Indian philosophy

- List of Nobel laureates in Literature

- Literary fiction – Well-written, non-genre, fiction

- Postcolonial Literature – Literature by people from formerly colonized countries

- Western culture – Norms, values, customs and political systems of the Western world

- Western education – Education from the Western world

- Women's writing in English – Academic discipline

- World literature – Circulation of literature beyond its country of origin

References

[edit]- ^ "SLE challenges the boundaries of the Western canon". www.stanforddaily.com. 26 January 2024. Retrieved 2024-07-24.

- ^ "Review: Foundational Myths of Multiculturalism and Strategies of Canon Formation". www.jstor.org. JSTOR 44029759. Retrieved 2024-07-24.

- ^ a b Wilczek, Piotr (2006). "Czy istnieje kanon literatury polskiej?". In Cudak, Romuald (ed.). Literatura polska w świecie (in Polish). Wydawnictwo Gnome. pp. 13–23. ISBN 978-83-87819-05-7.

- ^ Gellius, Aulus. Noctes Atticae (in Latin). pp. Book 19, Par. 8, Line 15. Archived from the original on March 25, 2008. Retrieved 5 November 2018.

- ^ Kennedy, George A. (2016). "The Origin of the Concept of a Canon and Its Application to the Greek and Latin Classics". In Gorek, Jan (ed.). Canon Vs. Culture | Reflections on the Current Debate. Routledge. ISBN 9781138988064.

- ^ Bloom, Harold (1994). The Western Canon: The Books and School of the Ages. New York: Harcourt Brace & Company. ISBN 9780151957477.

- ^ Casement, William. "College Great Books Programs". The Association for Core Texts and Courses (ACTC). Archived from the original on November 16, 2012. Retrieved May 29, 2012.

- ^ Giddins, Gary (1992-12-06). "Why I Carry a Torch For the Modern Library". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2024-07-22.

- ^ "Top 100 « Modern Library". www.modernlibrary.com.

- ^ Gerald J. Russello, The Postmodern Imagination of Russell Kirk (2007) p. 14

- ^ a b c Searle, John. (1990) "The Storm Over the University", The New York Review of Books, December 6, 1990.

- ^ Allan Bloom (2008), p. 344.

- ^ M. Keith Booker (2005). Encyclopedia of Literature and Politics: A–G. Greenwood. pp. 180–181. ISBN 9780313329395.

- ^ Jeffrey Williams, ed. PC wars: Politics and theory in the academy (Routledge, 2013)

- ^ Jefferson Lecturers Archived 2011-10-20 at the Wayback Machine at NEH Website (retrieved May 25, 2009).

- ^ Nadine Drozan, "Chronicle", The New York Times, May 6, 1992.

- ^ Bernard Knox, The Oldest Dead White European Males and Other Reflections on the Classics (1993) (reprint, W. W. Norton & Company, 1994), ISBN 978-0-393-31233-1.

- ^ Christopher Lehmann-Haupt, "Books of The Times; Putting In a Word for Homer, Herodotus, Plato, Etc.", The New York Times, April 29, 1993.

- ^ Pryor, Devon (2007). "What is a Literary Canon? (with pictures)". wisegeek.org. Archived from the original on 2007-12-26.

- ^ Compton, Todd M. (2015-04-19). "INFINITE CANONS: A FEW AXIOMS AND QUESTIONS, AND IN ADDITION, A PROPOSED DEFINITION". toddmcompton.com. Archived from the original on 2015-04-27.

- ^ Adler, Mortimer Jerome (1988). Reforming Education, Geraldine Van Doren, ed. (New York: MacMillan), p. xx.

- ^ "Great Books of Robert Maynard Hutchins and Mortimer Adler". Oxford Reference. Retrieved June 13, 2024.

- ^ "History of the Great Books Foundation". Great Books. Retrieved June 13, 2024.

- ^ a b Waller, Gary F. (2013). English Poetry of the Sixteenth Century. London: Routledge. pp. 263–270. ISBN 978-0582090965. Retrieved 30 March 2016.

- ^ Bednarz, James P. "English Poetry". Oxford Bibliographies. Archived from the original on 2014-10-18. Retrieved 2020-10-12.

- ^ "Life of Cowley", in Samuel Johnson's Lives of the Poets

- ^ Gary F. Waller, (2013). English Poetry of the Sixteenth Century. London: Routledge. p. 262

- ^ Alvarez, p. 11

- ^ Brown & Taylor (2004), ODNB

- ^ Poetry, LII (1939), pp. 258–272, excerpted in Paul. J. Alpers (ed): Elizabethan Poetry. Modern Essays in Criticism. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1967.

- ^ Poetry, LII (1939), pp. 258–272, excerpted in Paul. J. Alpers (ed): Elizabethan Poetry. Modern Essays in Criticism. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1967: 98

- ^ a b Blain, Virginia; Clements, Patricia; Grundy, Isobel (1990). The feminist companion to literature in English: women writers from the Middle Ages to the present. New Haven: Yale University Press. pp. vii–x. ISBN 0-300-04854-8.

- ^ Buck, Claire, ed. (1992). The Bloomsbury Guide to Women's Literature. Prentice Hall. p. vix.

- ^ Salzman, Paul (2000). "Introduction". Early Modern Women's Writing. Oxford UP. pp. ix–x.

- ^ Hardy Aiken, Susan (1986). "Women and the Question of Canonicity". College English. 48 (3): 289–292.

- ^ Hardy Aiken, Susan (1986). "Women and the Question of Canonicity". College English. 48 (3): 290–293.

- ^ Angela Leighton (1986). Elizabeth Barrett Browning. Indiana University Press. pp. 8–18. ISBN 978-0-253-25451-1. Retrieved 22 October 2011.

- ^ Bloom (1999), 9

- ^ Ford (1966), 122

- ^ a b "The Other Ghost in Beloved: The Specter of the Scarlet Letter" by Jan Stryz from The New Romanticism: a collection of critical essays by Eberhard Alsen, p. 140, ISBN 0-8153-3547-4.

- ^ Quote from Marjorie Pryse in "The Other Ghost in Beloved: The Specter of the Scarlet Letter" by Jan Stryz, from The New Romanticism: a collection of critical essays by Eberhard Alsen, p. 140, ISBN 0-8153-3547-4.

- ^ Mason, Theodore O. Jr. (1997). "African-American Theory and Criticism". The Johns Hopkins Guide to Literary Theory and Criticism. Archived from the original on 2000-01-15. Retrieved 2005-07-06.

- ^ Kinder, Emily (30 August 2018). "The 'literary canon' throughout the years". The Boar.

- ^ "All Nobel Prizes in Literature". NobelPrize.org. Retrieved 2023-11-06.

- ^ "Yasunari Kawabata – Facts". NobelPrize.org. Archived from the original on 2018-08-21. Retrieved June 11, 2014.

- ^ Haim Gordon (1990). Naguib Mahfouz's Egypt: Existential Themes in His Writings. Bloomsbury Academic. ISBN 0313268762.

- ^ "Oe, Pamuk: World needs imagination" Archived 2008-05-31 at the Wayback Machine, Yomiuri.co.jp; May 18, 2008.

- ^ Morrison, Donald (2005-02-14). "Holding Up Half the Sky". Time. Retrieved 2017-08-30.

- ^ Leach, Jim (Jan–Feb 2011). "The Real Mo Yan". Humanities. 32 (1): 11–13.

- ^ "Mo Yan får Nobelpriset i litteratur 2012". DN. 11 October 2012. Archived from the original on 15 February 2013. Retrieved 11 October 2012.

- ^ "The Nobel Prize in Literature 2012 Mo Yan". Nobelprize.org. 11 October 2012. Retrieved 11 October 2012.

- ^ Kinzer, Stephen (1998-12-15). "A Novelist Sees Dishonor in an Honor From the State". The New York Times. Retrieved 2008-08-30.

- ^ "Müzemi bitirdim mutluyum artık". Hürriyet. 2011-09-08. Retrieved 2011-10-11.

Altmış dile varmamıza şaşırdım. Bu yüksek bir rakam...

- ^ "En çok kazanan yazar kim?". Sabah (in Turkish). 2008-09-01. Retrieved 2008-09-02.

- ^ "Radikal-çevrimiçi / Türkiye / Orhan Pamuk: Aleyhimde kampanya var". Archived from the original on 2015-11-18. Retrieved 2015-11-03.

- ^ "García Márquez". Random House Webster's Unabridged Dictionary.

- ^ "The Nobel Prize in Literature 1982". Retrieved 18 April 2014.

- ^ Vulliamy, Ed (19 April 2014). "Gabriel García Márquez: 'The greatest Colombian who ever lived'". The Observer – via www.theguardian.com.

- ^ "Vargas Llosa" Archived December 31, 2014, at the Wayback Machine. Random House Webster's Unabridged Dictionary.

- ^ "Peru's Mario Vargas Llosa wins Nobel Literature Prize". The Independent. London. October 7, 2010.

- ^ Library of Congress to Honor Mario Vargas Llosa

- ^ "The Nobel Prize in Literature 2010". Nobelprize. October 7, 2010. Retrieved October 7, 2010.

- ^ Alfred North Whitehead (1929), Process and Reality, Part II, Chap. I, Sect. I.

- ^ Kevin Scharp (Department of Philosophy, Ohio State University) – Diagrams.

- ^ "...the subject of philosophy, as it is often conceived—a rigorous and systematic examination of ethical, political, metaphysical, and epistemological issues, armed with a distinctive method—can be called his invention" (Kraut, Richard (11 September 2013). Zalta, Edward N. (ed.). "Plato". The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Stanford University. Retrieved 3 April 2014.)

- ^ Cooper, John M.; Hutchinson, D. S., eds. (1997): "Introduction".

- ^ Bertrand Russell, A History of Western Philosophy, Simon & Schuster, 1972.

- ^ Marenbon, John (2021), Zalta, Edward N. (ed.), "Anicius Manlius Severinus Boethius", The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Winter 2021 ed.), Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University, retrieved 2024-12-17

- ^ Gibbon, Edward (1782). "Chapter XXXIX: Gothic Kingdom Of Italy, Part III". The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire. Vol. 4 (2nd ed.) (published 1845).

- ^ Russell, Bertrand (1961). History of Western Philosophy. London, England. p. 366.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Aloysius Martinich, Fritz Allhoff, Anand Vaidya, Early modern philosophy: essential readings with commentary. Oxford : Blackwell, 2007

- ^ Steadman, Ian. "Should We Forget the Thinker in the Text? Marsilio Ficino and the Challenges of Canon Formation." PhilArchive (2020). Accessed October 24, 2024. https://philarchive.org/archive/STESFT-4.

- ^ The following work discusses the importance of Neoplatonism as an essential part of the western canon: Hermes in the Academy: Ten Years’ Study of Western Esotericism at the University of Amsterdam. Accessed October 24, 2024. https://www.amsterdamhermetica.nl/wp-content/uploads/2013/05/Hermes-in-the-Academy.pdf.

- ^ a b "Western philosophy". Encyclopedia Britannica. 22 March 2024.

- ^ Bloom, Harold. The Western Canon: The Books and School of the Ages. Appendixes. New York: Harcourt Brace & Company, 1994. © 1994 by Harold Bloom

- ^ Körner, Axel (July 2009). "The Risorgimento's literary canon and the aesthetics of reception: some methodological considerations." Nations & Nationalism, 15(3), 410-418.

- ^ Rushton, Julian, Classical Music, (London, 1994), 10

- ^ "Classical", The Oxford Concise Dictionary of Music, ed. Michael Kennedy, (Oxford, 2007), Oxford Reference Online. Retrieved July 23, 2007.

- ^ "Ten Top Romantic Composers".Gramapne [1].

- ^ "Western Artists and Gamelan", CoastOnline.org. Archived 2014-03-07 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Ross, Alex (2008). The Rest Is Noise. London: Fourth Estate. p. 41. ISBN 978-1-84115-475-6.

- ^ Kostelanetz, Richard (1989), "Philip Glass", in Kostelanetz, Richard (ed.), Writings on Glass, Berkeley, Los Angeles; London: University of California Press, p. 109, ISBN 0-520-21491-9

- ^ La Barbara, Joan (1989), "Philip Glass and Steve Reich: Two from the Steady State School", in Kostelanetz, Richard (ed.), Writings on Glass, Berkeley, Los Angeles; London: University of California Press, pp. 40–41, ISBN 0-520-21491-9

- ^ "Overview of Baroque Instrumental Music | Music Appreciation 1". courses.lumenlearning.com. Retrieved 2023-07-04.

- ^ Citron, Marcia J. "Gender and the Musical Canon." CUP Archive, 1993.

- ^ Fiona Maddocks (2009-07-11). "Singin' through the pain". The Guardian. Retrieved 2016-12-26.

- ^ With nods in the text to Jan van Eyck and Albrecht Dürer, but not lives.

- ^ Gale, Matthew "Artist Biography: Barbara Hepworth 1903–75" Retrieved 31 January 2014.

- ^ "Art Gallery of Ontario partners with Tate Modern to present Georgia O'Keeffe retrospective in summer 2017 – AGO Art Gallery of Ontario". www.ago.net. Archived from the original on 2020-09-24. Retrieved 2016-11-29.

- ^ a b Nochlin, Linda (1971). "Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists?". Women, Art and Power and Other Essays. Westview Press.

- ^ Atkins, Robert (2013). Artspeak: A Guide to Contemporary Ideas, Movements, and Buzzwords, 1945 to the Present (3rd ed.). New York: Abbeville Press. ISBN 9780789211507. OCLC 855858296.

- ^ Chicago, Judy; Lucie-Smith, Edward (1999). Women and Art: Contested Territory. New York: Watson-Guptill Publications. p. 10. ISBN 0-8230-5852-2.

- ^ "La Pléiade". www.la-pleiade.fr.

- ^

- ^ "Revised Great Works Requirement Program" (PDF). 7 October 2013. pp. 1–25. Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 October 2013. Retrieved 14 March 2023.

- ^ "Language and Thinking Anthology". Bard College. Archived from the original on January 23, 2013. Retrieved July 11, 2012.

- ^ "University Scholars". University Scholars | Baylor University. 19 April 2023.

- ^ Michael Payne & John Hunter (eds). Renaissance Literature: an anthology. Oxford: Blackell, 2003, ISBN 0-631-19897-0, p. xix

- ^ David Norbrook & H. R. Woudhuysen (eds.): The Penguin Book of Renaissance Verse. London: Penguin Books, 1992, ISBN 0-14-042346-X

- ^ a b "Musils Mann ohne Eigenschaften ist 'wichtigster Roman des Jahrhunderts'" (in German). LiteraturHaus. 1999. Archived from the original on June 7, 2001. Retrieved August 21, 2012.

- ^ Wolfgang Riedel, "Robert Musil: Der Mann ohne Eigenschaften" in Lektüren für das 21. Jahrhundert: Schlüsseltexte der deutschen Literatur von 1200 bis 1900, ed. Dorothea Klein and Sabine M. Schneider, Würzburg: Königshausen & Neumann, 2000, ISBN 3-8260-1948-2, p. 265 (in German)

- ^ "Interviews". 18 May 2009. Archived from the original on 18 May 2009.

- ^ "Denmark/ 4. Current issues in cultural policy development and debate" Archived 2015-04-07 at the Wayback Machine, Compendium: Cultural Policies and Trends in Europe. Retrieved 11 January 2013.

- ^ "Kulturkanon", Den Store Danske. (in Danish) Retrieved 11 January 2013.

- ^ Ollé, Manel. La invenció de latradició literària (PDF) (in Catalan). Universitat Oberta de Catalunya.

- ^ "Las Cien Mejores Poesías (Líricas) de la Lengua Castellana – Marcelino Menéndez y Pelayo". www.camagueycuba.org.

- ^ Antonio Marco García, Propósitos filológicos de la colección «Clásicos Castellanos» de la editorial La Lectura (1910–1935), AIH, Actas, 1989.

Further reading

[edit]- Hirsch, E. D.; Trefil, James; Kett, Joseph F. (1988). The dictionary of cultural literacy. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 9780395437483.

- Guillory, John (1993). Cultural capital the problem of literary canon formation. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 9780226310442.

- Knox, Bernard (1994). The oldest dead white European males and other reflections on the classics. New York: W.W. Norton. ISBN 9780393312331.

- Bloom, Harold (1995). The Western canon: the books and school of the ages. New York: Riverhead Books. ISBN 9781573225144.

- Owens, W. R. (1996). Shakespeare, Aphra Behn, and the Canon. New York: Routledge in association with the Open University. ISBN 9780415135757.

- Bloom, Harold (1998). Shakespeare: The Invention of the Human. New York: Riverhead Books. ISBN 9781573227513.

- Ross, Trevor (1998). The making of the English literary canon from the Middle Ages to the late eighteenth century. Montreal Que: McGill-Queen's University Press. ISBN 9780773520806.

- Kolbas, E. Dean (2001). Critical Theory and the Literary Canon, Boulder: Westview Press. ISBN 0813398134

- Morrissey, Lee (2005). Debating the Canon: A Reader from Addison to Nafisii. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 9781403968203.

- Brzyski, Anna, ed. (2007). Partisan Canons. Duke University Press. ISBN 9780822341062.

- Owens, W. R. (2009), "The Canon and the curriculum", in Gupta, Suman; Katsarska, Milena (eds.), English studies on this side: post-2007 reckonings, Plovdiv, Bulgaria: Plovdiv University Press, pp. 47–59, ISBN 9789544235680

- Gorak, Jan (2013). The making of the modern canon: genesis and crisis of a literary idea. London: Bloomsbury Academic. ISBN 9781472513274.

- Carpeaux, Otto Maria (2014). Historia da literatura ocidental [The History of Western Literature] (in Portuguese). Rio de Janeiro: LeYa. ISBN 9788544101179. OCLC 889331083.

- Aston, Robert J. (2020). The role of the literary canon in the teaching of literature. New York: Routledge. ISBN 9780367432621.

External links

[edit]- "Great Books Lists: Lists of Classics, Eastern and Western": this has numerous lists, including Harold Bloom's

- Compton, "Infinite Canons: A Few Axioms and Questions, and in Addition, a Proposed Definition. A response to Harold Bloom"

- John Searle, "The Storm Over the University," The New York Review of Books, December 6, 1990