Columbus, Ohio

Columbus | |

|---|---|

|

| |

Interactive map of Columbus | |

| Coordinates: 39°57′44″N 83°00′02″W / 39.96222°N 83.00056°W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Ohio |

| Counties | |

| Settled | February 14, 1812 |

| Incorporated | February 10, 1816[1] |

| Named for | Christopher Columbus |

| Government | |

| • Type | Mayor–council |

| • Body | Columbus City Council |

| • Mayor | Andrew Ginther (D) |

| • Council members | List[2] |

| Area | |

| 226.26 sq mi (586.00 km2) | |

| • Land | 220.40 sq mi (570.82 km2) |

| • Water | 5.86 sq mi (15.18 km2) |

| Elevation | 791 ft (241 m) |

| Population (2020) | |

| 905,748 | |

• Estimate (2023)[5] | 913,175 |

| • Rank | 41st in North America 14th in the United States 1st in Ohio |

| • Density | 4,109.64/sq mi (1,586.74/km2) |

| • Urban | 1,567,254 (US: 35th) |

| • Urban density | 3,036.4/sq mi (1,172.3/km2) |

| • Metro | 2,138,926 (US: 32nd) |

| Demonym | Columbusite[7] |

| GDP | |

| • Columbus (MSA) | $169.1 billion (2022) |

| Time zone | UTC−5 (EST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−4 (EDT) |

| ZIP Codes | ZIP Codes[9] |

| Area codes | 614 and 380 |

| FIPS code | 39-18000 |

| GNIS feature ID | 1086101[4] |

| Website | www |

Columbus (/kəˈlʌmbəs/, kə-LUM-bəs) is the capital and most populous city of the U.S. state of Ohio. With a 2020 census population of 905,748,[10] it is the 14th-most populous city in the U.S., the second-most populous city in the Midwest (after Chicago), and the third-most populous U.S. state capital (after Phoenix, Arizona and Austin, Texas). Columbus is the county seat of Franklin County; it also extends into Delaware and Fairfield counties.[11] It is the core city of the Columbus metropolitan area, which encompasses ten counties in central Ohio.[12] It had a population of 2.139 million in 2020, making it the largest metropolitan area entirely in Ohio[a] and 32nd-largest metro area in the U.S.

Columbus originated as numerous Native American settlements on the banks of the Scioto River. Franklinton, now a city neighborhood, was the first European settlement, laid out in 1797. The city was founded in 1812 at the confluence of the Scioto and Olentangy rivers, and laid out to become the state capital. The city was named for Italian explorer Christopher Columbus.[14] The city assumed the function of state capital in 1816 and county seat in 1824. Amid steady years of growth and industrialization, the city has experienced numerous floods and recessions. Beginning in the 1950s, Columbus began to experience significant growth; it became the largest city in Ohio in land and population by the early 1990s. Growth has continued in the 21st century, with redevelopment occurring in numerous city neighborhoods, including Downtown.

The city has a diverse economy without reliance on any one sector. The metropolitan area is home to the Battelle Memorial Institute, the world's largest private research and development foundation; Chemical Abstracts Service, the world's largest clearinghouse of chemical information; and the Ohio State University, one of the largest universities in the United States. The Greater Columbus area is further home to the headquarters of six Fortune 500 companies, namely Cardinal Health, American Electric Power, Bath & Body Works, Inc., Nationwide, Bread Financial and Huntington Bancshares.

Name

The city of Columbus was named after 15th-century Italian explorer Christopher Columbus at the city's founding in 1812.[14] It is the largest city in the world named for the explorer, who sailed to and settled parts of the Americas on behalf of Isabella I of Castile and Spain.[15] Although no reliable history exists as to why Columbus, who had no connection to the city or state of Ohio before the city's founding, was chosen as the name for the city, the book Columbus: The Story of a City indicates a state lawmaker and local resident admired the explorer enough to persuade other lawmakers to name the settlement Columbus.[14][16]

Since the late 20th century, historians have criticized Columbus for initiating the European conquest of America and for abuse, enslavement, and subjugation of natives.[17][18] Efforts to remove symbols related to the explorer in the city date to the 1990s.[16] Amid the George Floyd protests in 2020, several petitions pushed for the city to be renamed.[19]

Nicknames for the city have included "the Discovery City",[20] "Arch City",[21][22][23] "Cap City",[24][25] "Cowtown", "The Biggest Small Town in America"[26][27][28] and "Cbus."[29]

History

Ancient and early history

Between 1000 B.C. and 1700 A.D., the Columbus metropolitan area was a center to indigenous cultures known as the Mound Builders, including the Adena, Hopewell and Fort Ancient peoples. Remaining physical evidence of the cultures are their burial mounds and what they contained. Most of Central Ohio's remaining mounds are located outside of Columbus city boundaries, though the Shrum Mound is maintained, now as part of a public park and historic site. The city's Mound Street derives its name from a mound that existed by the intersection of Mound and High Streets. The mound's clay was used in bricks for most of the city's initial brick buildings; many were subsequently used in the Ohio Statehouse. The city's Ohio History Center maintains a collection of artifacts from these cultures.[30]

18th century

The area including present-day Columbus once comprised the Ohio Country,[31] under the nominal control of the French colonial empire through the Viceroyalty of New France from 1663 until 1763.

In the 18th century, European traders flocked to the area, attracted by the fur trade.[32] The area was often caught between warring factions, including American Indian and European interests. In the 1740s, Pennsylvania traders overran the territory until the French forcibly evicted them.[33] Fighting for control of the territory in the French and Indian War (1754–1763) became part of the international Seven Years' War (1756–1763). During this period, the region routinely suffered turmoil, massacres and battles. The 1763 Treaty of Paris ceded the Ohio Country to the British Empire.

Up until the American Revolution, Central Ohio had continuously been the home of numerous indigenous villages. A Mingo village was located at the forks of the Scioto and Olentangy rivers, with Shawnee villages to the south and Wyandot and Delaware villages to the north. Colonial militiamen burned down the Mingo village in 1774 during a raid.[34]

Virginia Military District

After the American Revolution, the Virginia Military District became part of the Ohio Country as a territory of Virginia. Colonists from the East Coast moved in, but rather than finding an empty frontier, they encountered people of the Miami, Delaware, Wyandot, Shawnee and Mingo nations, as well as European traders. The tribes resisted expansion by the fledgling United States, leading to years of bitter conflict. The decisive Battle of Fallen Timbers resulted in the Treaty of Greenville in 1795, which finally opened the way for new settlements. By 1797, a young surveyor from Virginia named Lucas Sullivant had founded a permanent settlement on the west bank of the forks of the Scioto and Olentangy rivers. An admirer of Benjamin Franklin, Sullivant chose to name his frontier village "Franklinton."[35] The location was desirable for its proximity to the navigable rivers – but Sullivant was initially foiled when, in 1798, a large flood wiped out the new settlement.[36] He persevered, and the village was rebuilt, though somewhat more inland.

After the Revolution, land comprising parts of Franklin and adjacent counties was set aside by the United States Congress for settlement by Canadians and Nova Scotians who were sympathetic to the colonial cause and had their land and possessions seized by the British government. The Refugee Tract, consisting of 103,000 acres (42,000 ha), was 42 miles (68 km) long and 3–4.5 miles (4.8–7.2 km) wide, and was claimed by 67 eligible men. The Ohio Statehouse sits on land once contained in the Refugee Tract.[37]

19th century

After Ohio achieved statehood in 1803, political infighting among prominent Ohio leaders led to the state capital moving from Chillicothe to Zanesville and back again. Desiring to settle on a location, the state legislature considered Franklinton, Dublin, Worthington and Delaware before compromising on a plan to build a new city in the state's center, near major transportation routes, primarily rivers. As well, Franklinton landowners had donated two 10-acre (4.0 ha) plots in an effort to convince the state to move its capital there.[38] The two spaces were set to become Capitol Square, including for the Ohio Statehouse and the Ohio Penitentiary. Named in honor of Christopher Columbus, the city was founded on February 14, 1812, on the "High Banks opposite Franklinton at the Forks of the Scioto most known as Wolf's Ridge."[39] At the time, this area was a dense forestland, used only as a hunting ground.[40]

The city was incorporated as a borough on February 10, 1816.[1] Between 1816 and 1817, Jarvis W. Pike served as the first appointed mayor. Although the recent War of 1812 had brought prosperity to the area, the subsequent recession and conflicting claims to the land threatened the new town's success. Early conditions were abysmal, with frequent bouts of fevers, attributed to malaria from the flooding rivers, and an outbreak of cholera in 1833. It led Columbus to create the Board of Health, now part of the Columbus Public Health department. The outbreak, which remained in the city from July to September 1833, killed 100 people.[41]

Columbus was without direct river or trail connections to other Ohio cities, leading to slow initial growth. The National Road reached Columbus from Baltimore in 1831, which complemented the city's new link to the Ohio and Erie Canal, both of which facilitated a population boom.[42][41] A wave of European immigrants led to the creation of two ethnic enclaves on the city's outskirts. A large Irish population settled in the north along Naghten Street (presently Nationwide Boulevard), while the Germans took advantage of the cheap land to the south, creating a community that came to be known as the Das Alte Südende (The Old South End). Columbus's German population constructed numerous breweries, Trinity Lutheran Seminary and Capital University.[43]

With a population of 3,500, Columbus was officially chartered as a city on March 3, 1834. On that day, the legislature carried out a special act, which granted legislative authority to the city council and judicial authority to the mayor. Elections were held in April of that year, with voters choosing John Brooks as the first popularly elected mayor.[44] Columbus annexed the then-separate city of Franklinton in 1837.[45]

In 1850, the Columbus and Xenia Railroad became the first railroad into the city, followed by the Cleveland, Columbus and Cincinnati Railroad in 1851. The two railroads built a joint Union Station on the east side of High Street just north of Naghten (then called North Public Lane). Rail traffic into Columbus increased: by 1875, eight railroads served Columbus, and the rail companies built a new, more elaborate station.[46] Another cholera outbreak hit Columbus in 1849, prompting the opening of the city's Green Lawn Cemetery.[47] On January 7, 1857, the Ohio Statehouse finally opened after 18 years of construction.[48]

Before the abolition of slavery in the Southern United States in 1863, the Underground Railroad was active in Columbus and was led, in part, by James Preston Poindexter.[49] Poindexter arrived in Columbus in the 1830s and became a Baptist preacher and leader in the city's African-American community until the turn of the century.[50]

During the Civil War, Columbus was a major base for the volunteer Union Army. It housed 26,000 troops and held up to 9,000 Confederate prisoners of war at Camp Chase, at what is now the Hilltop neighborhood of west Columbus. Over 2,000 Confederate soldiers remain buried at the site, making it one of the North's largest Confederate cemeteries.[51]

By virtue of the Morrill Act of 1862, the Ohio Agricultural and Mechanical College – which eventually became the Ohio State University – was founded in 1870 on the former estate of William and Hannah Neil.[52]

By the end of the 19th century, Columbus was home to several major manufacturing businesses. The Jeffrey Manufacturing Company was a major supplier of coal mining equipment.[53] The city became known as the "Buggy Capital of the World," thanks to the two dozen buggy factories – notably the Columbus Buggy Company, founded in 1875 by C.D. Firestone.[54] The Columbus Consolidated Brewing Company also rose to prominence during this time and might have achieved even greater success were it not for the Anti-Saloon League in neighboring Westerville.[55]

In the steel industry, a forward-thinking man named Samuel P. Bush presided over the Buckeye Steel Castings Company. Columbus was also a popular location for labor organizations. In 1886, Samuel Gompers founded the American Federation of Labor in Druid's Hall on South Fourth Street, and in 1890, the United Mine Workers of America was founded at the old City Hall.[56]

20th century

Columbus earned one of its nicknames, "The Arch City," because of the dozens of wooden arches that spanned High Street at the turn of the 20th century. The arches illuminated the thoroughfare and eventually became the means by which electric power was provided to the new streetcars. The city tore down the arches and replaced them with cluster lights in 1914 but reconstructed them from metal in the Short North neighborhood in 2002 for their unique historical interest.[57]

On March 25, 1913, the Great Flood of 1913 devastated the neighborhood of Franklinton, leaving over 90 people dead and thousands of West Side residents homeless. To prevent flooding, the Army Corps of Engineers recommended widening the Scioto River through downtown, constructing new bridges and building a retaining wall along its banks. With the strength of the post-World War I economy, a construction boom occurred in the 1920s, resulting in a new civic center, the Ohio Theatre, the American Insurance Union Citadel and to the north, a massive new Ohio Stadium.[58] Although the American Professional Football Association was founded in Canton in 1920, its head offices moved to Columbus in 1921 to the New Hayden Building and remained in the city until 1941.

In 1922, the association's name was changed to the National Football League.[59] Nearly a decade later, in 1931, at a convention in the city, the Jehovah's Witnesses took that name by which they are known today.

The effects of the Great Depression were less severe in Columbus, as the city's diversified economy helped it fare better than its Rust Belt neighbors. World War II brought many new jobs and another population surge. This time, most new arrivals were migrants from the "extraordinarily depressed rural areas" of Appalachia, who would soon account for more than a third of Columbus's growing population.[60] In 1948, the Town and Country Shopping Center opened in suburban Whitehall, and it is now regarded as one of the first modern shopping centers in the United States.[61]

The construction of the Interstate Highway System signaled the arrival of rapid suburb development in central Ohio. To protect the city's tax base from this suburbanization, Columbus adopted a policy of linking sewer and water hookups to annexation to the city.[62] By the early 1990s, Columbus had grown to become Ohio's largest city in land area and in population.

Efforts to revitalize downtown Columbus have had some success in recent decades,[63] though like most major American cities, some architectural heritage was lost in the process. In the 1970s, landmarks such as Union Station and the Neil House hotel were razed to construct high-rise offices and big retail space. The PNC Bank building was constructed in 1977, as well as the Nationwide Plaza buildings and other towers that sprouted during this period. The construction of the Greater Columbus Convention Center has brought major conventions and trade shows to the city.

21st century

The Scioto Mile began development along the riverfront, an area that already had the Miranova Corporate Center and The Condominiums at North Bank Park.

The 2010 United States foreclosure crisis forced the city to purchase numerous foreclosed, vacant properties to renovate or demolish them – at a cost of tens of millions of dollars. In February 2011, Columbus had 6,117 vacant properties, according to city officials.[64]

Since 2010, Columbus has been growing in population and economy; from 2010 to 2017, the city added 164,000 jobs, which ranked second in the United States.[citation needed] In February and March 2020, Columbus reported its first official cases of COVID-19 and declared a state of emergency, with all nonessential businesses closed statewide. There were 69,244 cases of the disease across the city, as of March 11, 2021[update].[65] Later in 2020, protests over the murder of George Floyd took place in the city from May 28 into August.[66] Columbus and its metro area have experienced growth in the high-tech manufacturing sector, with Intel announcing plans to construct a $20 billion factory and Honda expanding its presence along with LG Energy Solutions with a $4.4 billion battery manufactory facility in Fayette County.[67][68]

The COVID-19 pandemic muted activity in Columbus, especially in its downtown core, from 2020 to 2022. By late 2022, foot traffic in Downtown Columbus began to exceed pre-pandemic rates; one of the quickest downtown areas to recover in the United States.[69]

On June 23, 2023, ten people were injured in a mass shooting in the city's Short North district.

Ransomware attack

In July 2024, Columbus was subject to a ransomware attack, for which the hacker group Rhysidia took credit.[70] In August 2024, Columbus Mayor Andrew Ginther claimed that the files obtained by Rhysidia were "unusable" to the thieves due to being either encrypted or corrupted.[71] Ginther's assertion was subsequently shown to be false by security researcher David Leroy Ross (who goes by the alias Connor Goodwolf), who revealed that the files were intact and contained data including names from domestic violence cases and Social Security numbers of crime victims.[72] Columbus then sued Ross for alleged criminal acts, negligence, and civil conversion, as well as taking out a restraining order against Ross, both of which actions were later defended by City Attorney Zach Klein.[73] In response, a number of prominent cybersecurity researchers called on the city to drop the lawsuit.[74]

Neo-Nazi march

On Saturday November 19 2024 about a dozen men dressed in black and masked carried red swastika flags in Columbus making racist slurs and using pepper speech. The group identified themselves as "Hate Club". Oren Segal, ADL vice-president, said that this might related to the hate group Blood Tribe "Blood Tribe views itself as the main white supremacist group in Ohio, so ... (the) 'Hate Club' march appears to have been an intentional effort to antagonize them."[75][76]

Geography

The confluence of the Scioto and Olentangy rivers is just northwest of Downtown Columbus. Several smaller tributaries course through the Columbus metropolitan area, including Alum Creek, Big Walnut Creek and Darby Creek. Columbus is considered to have relatively flat topography thanks to a large glacier that covered most of Ohio during the Wisconsin Ice Age. However, there are sizable differences in elevation through the area, with the high point of Franklin County being 1,132 ft (345 m) above sea level near New Albany, and the low point being 670 ft (200 m) where the Scioto River leaves the county near Lockbourne.[77]

Several ravines near the rivers and creeks also add variety to the landscape. Tributaries to Alum Creek and the Olentangy River cut through shale, while tributaries to the Scioto River cut through limestone. The numerous rivers and streams beside low-lying areas in Central Ohio contribute to a history of flooding in the region; the most significant was the Great Flood of 1913 in Columbus, Ohio.[78]

The city has a total area of 223.11 square miles (577.85 km2), of which 217.17 square miles (562.47 km2) is land and 5.94 square miles (15.38 km2) is water.[79] Columbus currently has the largest land area of any Ohio city; this is due to Jim Rhodes's tactic to annex suburbs while serving as mayor. As surrounding communities grew or were constructed, they came to require access to waterlines, which was under the sole control of the municipal water system. Rhodes told these communities that if they wanted water, they would have to submit to assimilation into Columbus.[80]

Neighborhoods

Columbus has a wide diversity of neighborhoods with different characters,[81] and is thus sometimes known as a "city of neighborhoods."[82][83] Some of the most prominent neighborhoods include the Arena District, the Brewery District, Clintonville, Franklinton, German Village, The Short North and Victorian Village.[81]

Climate

The city's climate is humid continental (Köppen climate classification Dfa) transitional with the humid subtropical (Köppen climate classification Cfa) to the south characterized by warm, muggy summers and cold, dry winters. Columbus is within USDA hardiness zone 6b, bordering on 7a. Winter snowfall is relatively light, since the city is not in the typical path of strong winter lows, such as the Nor'easters that strike cities farther east. It is also too far south and west for lake-effect snow from Lake Erie to have much effect, although the lakes to the north contribute to long stretches of cloudy spells in winter.

The highest temperature recorded in Columbus is 106 °F (41 °C), which occurred twice during the Dust Bowl of the 1930s: once on July 21, 1934, and again on July 14, 1936.[84] The lowest recorded temperature was −22 °F (−30 °C), occurring on January 19, 1994.[84]

Columbus is subject to severe weather typical to the Midwestern United States. Severe thunderstorms can bring lightning, large hail and on rare occasions tornadoes, especially during the spring and sometimes through fall. A tornado that occurred on October 11, 2006, caused F2 damage.[85] Floods, blizzards and ice storms can also occur from time to time.

| Climate data for Columbus, Ohio (John Glenn Int'l), 1991–2020 normals,[b] extremes 1878–present[c] | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 74 (23) |

78 (26) |

85 (29) |

90 (32) |

96 (36) |

102 (39) |

106 (41) |

103 (39) |

100 (38) |

94 (34) |

80 (27) |

76 (24) |

106 (41) |

| Mean maximum °F (°C) | 60.7 (15.9) |

64.1 (17.8) |

73.6 (23.1) |

81.6 (27.6) |

88.3 (31.3) |

93.1 (33.9) |

93.7 (34.3) |

92.8 (33.8) |

90.2 (32.3) |

83.2 (28.4) |

70.5 (21.4) |

62.5 (16.9) |

95.0 (35.0) |

| Mean daily maximum °F (°C) | 37.1 (2.8) |

40.8 (4.9) |

51.1 (10.6) |

64.1 (17.8) |

74.1 (23.4) |

82.2 (27.9) |

85.4 (29.7) |

84.1 (28.9) |

77.8 (25.4) |

65.5 (18.6) |

52.3 (11.3) |

41.5 (5.3) |

63.0 (17.2) |

| Daily mean °F (°C) | 29.6 (−1.3) |

32.5 (0.3) |

41.6 (5.3) |

53.2 (11.8) |

63.3 (17.4) |

71.9 (22.2) |

75.4 (24.1) |

74.0 (23.3) |

67.2 (19.6) |

55.2 (12.9) |

43.6 (6.4) |

34.5 (1.4) |

53.5 (11.9) |

| Mean daily minimum °F (°C) | 22.0 (−5.6) |

24.2 (−4.3) |

32.0 (0.0) |

42.2 (5.7) |

52.4 (11.3) |

61.6 (16.4) |

65.4 (18.6) |

63.9 (17.7) |

56.5 (13.6) |

44.8 (7.1) |

35.0 (1.7) |

27.4 (−2.6) |

43.9 (6.6) |

| Mean minimum °F (°C) | 1.7 (−16.8) |

6.3 (−14.3) |

14.5 (−9.7) |

27.1 (−2.7) |

37.8 (3.2) |

48.6 (9.2) |

55.7 (13.2) |

54.3 (12.4) |

43.2 (6.2) |

31.1 (−0.5) |

20.6 (−6.3) |

11.0 (−11.7) |

−0.9 (−18.3) |

| Record low °F (°C) | −22 (−30) |

−20 (−29) |

−6 (−21) |

14 (−10) |

25 (−4) |

35 (2) |

43 (6) |

39 (4) |

31 (−1) |

17 (−8) |

−5 (−21) |

−17 (−27) |

−22 (−30) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 3.00 (76) |

2.41 (61) |

3.62 (92) |

3.85 (98) |

3.99 (101) |

4.33 (110) |

4.67 (119) |

3.74 (95) |

3.14 (80) |

2.90 (74) |

2.79 (71) |

3.13 (80) |

41.57 (1,056) |

| Average snowfall inches (cm) | 9.5 (24) |

7.6 (19) |

4.1 (10) |

0.5 (1.3) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.2 (0.51) |

1.2 (3.0) |

5.1 (13) |

28.2 (72) |

| Average extreme snow depth inches (cm) | 4.4 (11) |

3.7 (9.4) |

2.4 (6.1) |

0.1 (0.25) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.4 (1.0) |

2.3 (5.8) |

6.6 (17) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.01 in) | 14.7 | 11.8 | 12.5 | 13.7 | 14.0 | 11.7 | 10.9 | 9.5 | 8.7 | 10.0 | 10.5 | 12.7 | 140.7 |

| Average snowy days (≥ 0.1 in) | 9.0 | 6.7 | 4.0 | 1.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 1.9 | 5.6 | 28.3 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 71.4 | 69.5 | 64.5 | 62.5 | 66.5 | 68.5 | 70.6 | 72.8 | 72.8 | 69.3 | 71.8 | 74.1 | 69.5 |

| Average dew point °F (°C) | 18.1 (−7.7) |

20.5 (−6.4) |

28.6 (−1.9) |

37.4 (3.0) |

48.9 (9.4) |

58.3 (14.6) |

62.8 (17.1) |

61.7 (16.5) |

55.2 (12.9) |

42.6 (5.9) |

33.6 (0.9) |

24.3 (−4.3) |

41.0 (5.0) |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 110.6 | 126.3 | 162.0 | 201.8 | 243.4 | 258.1 | 260.9 | 235.9 | 212.0 | 183.1 | 104.2 | 84.3 | 2,182.6 |

| Percent possible sunshine | 37 | 42 | 44 | 51 | 55 | 57 | 57 | 56 | 57 | 53 | 35 | 29 | 49 |

| Average ultraviolet index | 2 | 3 | 4 | 6 | 8 | 9 | 9 | 8 | 6 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 5 |

| Source: NOAA (sun, relative humidity, and dew point 1961–1990)[86][87][88][89] and Weather Atlas[90] | |||||||||||||

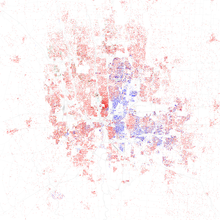

Demographics

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1812 | 300 | — |

| 1820 | 1,450 | +383.3% |

| 1830 | 2,435 | +67.9% |

| 1840 | 6,048 | +148.4% |

| 1850 | 17,882 | +195.7% |

| 1860 | 18,554 | +3.8% |

| 1870 | 31,274 | +68.6% |

| 1880 | 51,647 | +65.1% |

| 1890 | 88,150 | +70.7% |

| 1900 | 125,560 | +42.4% |

| 1910 | 181,511 | +44.6% |

| 1920 | 237,031 | +30.6% |

| 1930 | 290,564 | +22.6% |

| 1940 | 306,087 | +5.3% |

| 1950 | 375,901 | +22.8% |

| 1960 | 471,316 | +25.4% |

| 1970 | 539,677 | +14.5% |

| 1980 | 564,871 | +4.7% |

| 1990 | 632,910 | +12.0% |

| 2000 | 711,470 | +12.4% |

| 2010 | 787,033 | +10.6% |

| 2020 | 905,748 | +15.1% |

| 2023 est. | 913,175 | +0.8% |

| 1812,[91] 1820-2019: U.S. Census[92][93] Source: U.S. Decennial Census[94] | ||

| Historical racial composition | 2020[95] | 2010[96] | 1990[97] | 1970[97] | 1950[97] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| White | 57.4% | 61.5% | 74.4% | 81.0% | 87.5% |

| —Non-Hispanic | 54.3% | 59.3% | 73.8% | 80.4%[d] | n/a |

| Black or African American | 29.2% | 28.0% | 22.6% | 18.5% | 12.4% |

| Hispanic or Latino (of any race) | 6.3% | 5.6% | 1.1% | 0.6%[d] | n/a |

| Asian | 5.9% | 4.1% | 2.4% | 0.2% | 0.1% |

2020 census

In the 2020 United States census, there were 905,748 people living in the city, for a population density of 4,109.64 people per square mile (1,586.74/km2). There were 415,456 housing units. The racial makeup of the city was 57.4% White, 29.2% Black or African American, 0.2% Native American or Alaska Native, and 5.9% Asian. Hispanic or Latino of any race made up 6.3% of the population.[98][99]

There were 392,041 households, out of which 25.5% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 30.8% were married couples living together, 25.1% had a male householder with no spouse present, and 33.7% had a female householder with no spouse present. 37.1% of all households were made up of individuals, and 9.7% were someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.26, and the average family size was 3.03.[99]

21.0% of the city's population were under the age of 18, 67.5% were 18 to 64, and 11.5% were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 33.3. For every 100 females, there were 97.3 males.[99]

According to the U.S. Census American Community Survey, for the period 2016-2020 the estimated median annual income for a household in the city was $61,727, and the median income for a family was $76,383. About 18.1% of the population were living below the poverty line, including 26.1% of those under age 18 and 12.0% of those age 65 or over. About 67.2% of the population were employed, and 38.5% had a bachelor's degree or higher.[99]

| Race / Ethnicity (NH = Non-Hispanic) | Pop 2000[100] | Pop 2010[101] | Pop 2020[102] | % 2000 | % 2010 | 2020 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| White alone (NH) | 475,897 | 466,615 | 470,705 | 66.89% | 59.29% | 51.97% |

| Black or African American alone (NH) | 172,750 | 217,694 | 256,509 | 24.28% | 27.66% | 28.32% |

| Native American or Alaska Native alone (NH) | 1,858 | 1,643 | 1,632 | 0.26% | 0.21% | 0.18% |

| Asian alone (NH) | 24,386 | 31,734 | 55,932 | 3.43% | 4.03% | 6.18% |

| Pacific Islander alone (NH) | 326 | 462 | 325 | 0.05% | 0.06% | 0.04% |

| Other race alone (NH) | 1,824 | 2,032 | 5,369 | 0.26% | 0.26% | 0.59% |

| Mixed race or Multiracial (NH) | 16,958 | 22,494 | 45,097 | 2.38% | 2.86% | 4.98% |

| Hispanic or Latino (any race) | 17,471 | 44,359 | 70,179 | 2.46% | 5.64% | 7.75% |

| Total | 711,470 | 787,033 | 905,748 | 100.00% | 100.00% | 100.00% |

2010 census

In the 2010 United States census, there were 787,033 people, 331,602 households and 176,037 families residing in the city. The population density was 3,624 inhabitants per square mile (1,399.2/km2). There were 370,965 housing units at an average density of 1,708.2 per square mile (659.5/km2).

The racial makeup of the city included 815,985 races tallied, as some residents recognized multiple races. The racial makeup was 61.9% White, 29.1% Black or African American, 1% Native American or Alaska Native, 4.6% Asian, 0.2% Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander, and 3.2% from other races.[103] Hispanic or Latino of any race were 5.9% of the population.[104]

Population makeup

Columbus historically had a significant population of white people. In 1900, whites made up 93.4% of the population.[97] Although European immigration has declined, the Columbus metropolitan area has recently experienced increases in African, Asian and Latin American immigration, including groups from Mexico, India, Nepal, Bhutan, Somalia and China. While the Asian population is diverse, the city's Hispanic community is mainly made up of Mexican Americans, although there is a notable Puerto Rican population.[105] Many other countries of origin are represented in lesser numbers, largely due to the international draw of Ohio State University. 2008 estimates indicate that roughly 116,000 of the city's residents are foreign-born, accounting for 82% of the new residents between 2000 and 2006 at a rate of 105 per week.[106] 40% of the immigrants came from Asia, 23% from Africa, 22% from Latin America and 13% from Europe.[106] The city had the second-largest Somali and Somali American population in the country, as of 2004, as well as the largest expatriate Bhutanese-Nepali population in the world, as of 2018.[107][108]

Due to its demographics, which include a mix of races and a wide range of incomes, as well as urban, suburban and nearby rural areas, Columbus is considered a "typical" American city, leading retail and restaurant chains to use it as a test market for new products.[109] For similar reasons, the city was chosen as the launch city for the QUBE cable television service.

Columbus has maintained a steady population growth since its establishment. Its slowest growth, from 1850 to 1860, is primarily attributed to the city's cholera epidemic in the 1850s.[110]

According to the 2017 Japanese Direct Investment Survey by the Consulate-General of Japan, Detroit, 838 Japanese nationals lived in Columbus, making it the municipality with the state's second-largest Japanese national population, after Dublin.[111]

Columbus is home to a proportional LGBT community, with an estimated 34,952 gay, lesbian or bisexual residents.[112] The 2018 American Community Survey (ACS) reported an estimated 366,034 households, 32,276 of which were held by unmarried partners. 1,395 of these were female householder and female-partner households, and 1,456 were male householder and male-partner households.[113] Columbus has been rated as one of the best cities in the country for gays and lesbians to live, and also as the most underrated gay city in the country.[114] In July 2012, three years prior to legal same-sex marriage in the United States, the Columbus City Council unanimously passed a domestic partnership registry.[115]

Italian-American community and symbols

Columbus has numerous Italian Americans, with groups including the Columbus Italian Club, Columbus Piave Club and the Abruzzi Club.[116] Italian Village, a neighborhood near Downtown Columbus, has had a prominent Italian American community since the 1890s.[117]

The community has helped promote the influence Christopher Columbus had in drawing European attention to the Americas. The Italian explorer, erroneously credited with the lands' discovery, has been posthumously criticized by historians for initiating colonization and for abuse, enslavement and subjugation of natives.[18][17] In addition to the city being named for the explorer, its seal and flag depict a ship he used for his first voyage to the Americas, the Santa María. A similar-size replica of the ship, the Santa Maria Ship & Museum, was displayed downtown from 1991 to 2014.[118] The city's Discovery District and Discovery Bridge are named in reference to Columbus's "discovery" of the Americas; the bridge includes artistic bronze medallions featuring symbols of the explorer.[119][120] Genoa Park, downtown, is named after Genoa, the birthplace of Christopher Columbus and one of Columbus's sister cities.[121]

The Christopher Columbus Quincentennial Jubilee, celebrating the 500th anniversary of Columbus's first voyage, was held in the city in 1992. Its organizers spent $95 million on it, creating the horticultural exhibition AmeriFlora '92. The organizers also planned to create a replica Native American village, among other attractions. Local and national native leaders protested the event with a day of mourning, followed by protests and fasts at City Hall. The protests prevented the native village from being exhibited, and annual fasts continued until 1997. A protest also took place during the dedication of the Santa Maria replica, an event held in late 1991 on the day before Columbus Day and in time for the jubilee.[16][14]

The city has three outdoor statues of the explorer; the statue at City Hall was acquired, delivered and dedicated with the assistance of the Italian American community. Protests in 2017 aimed for this statue to be removed,[122] followed by the city in 2018 ceasing to recognize Columbus Day as a city holiday.[123] During the 2020 George Floyd protests, petitions were created to remove all three statues and rename the city of Columbus.[19]

The city was one of eight cities to be offered the 360 ft (110 m) Birth of the New World statue, in 1993. The statue, also of Christopher Columbus, was completed in Puerto Rico in 2016 and is the tallest in the United States – 45 ft (14 m) taller than the Statue of Liberty, including its pedestal. At least six U.S. cities, including Columbus, rejected it based on its height and design.[124]

Religion

According to the 2019 American Values Atlas, 26% of Columbus metropolitan area residents are unaffiliated with a religious tradition. 17% of area residents identify as White evangelical Protestants, 14% as White mainline Protestants, 11% as Black Protestants, 11% as White Catholics, 5% as Hispanic Catholics, 3% as other nonwhite Catholics, 2% as other nonwhite Protestants and 2% as Mormons. Hindus, Buddhists, Jews and Latino Protestants each made up 1% of the population, while Jehovah's Witnesses, Orthodox Christians, Muslims, Unitarians, and members of New Age or other religions each made up under 0.5% of the population.[125]

Places of worship include Baptist, Evangelical, Greek Orthodox, Latter-day Saints, Lutheran, Presbyterian, Quaker, Roman Catholic, and Unitarian Universalist churches. Columbus also hosts several Islamic mosques, Jewish synagogues, Buddhist centers, Hindu temples and a branch of the International Society for Krishna Consciousness. Religious teaching institutions include the Pontifical College Josephinum and several private schools led by Christian organizations.

Economy

Columbus has a generally strong and diverse economy based on education, insurance, banking, fashion, defense, aviation, food, logistics, steel, energy, medical research, health care, hospitality, retail and technology. In 2010, it was one of the 10 best big cities in the country, according to Relocate America, a real estate research firm.[126]

According to the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, the GDP of Columbus in 2019 was $134 billion (~$158 billion in 2023).[127]

During the Great Recession between 2007 and 2009, Columbus's economy was not impacted as much as the rest of the country, due to decades of diversification work by long-time corporate residents, business leaders and political leaders. The administration of former mayor Michael B. Coleman continued this work, although the city faced financial turmoil and had to increase taxes, allegedly due in part to fiscal mismanagement.[128][129] Because Columbus is the state capital, there is a large government presence in the city. Including city, county, state and federal employers, government jobs provide the largest single source of employment within Columbus.

In 2019, the city had six corporations named to the U.S. Fortune 500 list: Alliance Data, Nationwide Mutual Insurance Company, American Electric Power, L Brands, Huntington Bancshares and Cardinal Health in suburban Dublin.[130][131] Other major employers include schools (e.g., Ohio State University) and hospitals (among others, Wexner Medical Center and Nationwide Children's Hospital, which are among the teaching hospitals of the Ohio State University College of Medicine), high-tech research and development such as the Battelle Memorial Institute, information/library companies such as OCLC and Chemical Abstracts Service, steel processing and pressure cylinder manufacturer Worthington Industries, financial institutions such as JPMorgan Chase and Huntington Bancshares, as well as Owens Corning. Fast-food chains Wendy's and White Castle are also headquartered in the Columbus area. Major foreign corporations operating or with divisions in the city include Germany-based Siemens and Roxane Laboratories, Finland-based Vaisala, Tomasco Mulciber Inc., A Y Manufacturing, as well as Switzerland-based ABB and Mettler Toledo. The city also has a significant fashion and retail presence, home to companies such as Big Lots, L Brands, Abercrombie & Fitch, DSW and Express.

Food and beverage industry

North Market, a public market and food hall, is located downtown near the Short North. It is the only remaining public market of Columbus's original four marketplaces.

Numerous restaurant chains are based in the Columbus area, including Charleys Philly Steaks, Bibibop Asian Grill, Steak Escape, White Castle, Cameron Mitchell Restaurants, Bob Evans Restaurants, Max & Erma's, Damon's Grill, Donatos Pizza and Wendy's. Wendy's, the world's third-largest hamburger fast-food chain, operated its first store downtown as both a museum and a restaurant until March 2007, when the establishment was closed due to low revenue. The company is presently headquartered outside the city in nearby Dublin. Budweiser has a major brewery located on the north side, just south of I-270 and Worthington. Columbus is also home to many local micro breweries and pubs. Asian frozen food manufacturer Kahiki Foods was located on the east side of Columbus, created during the operation of the Kahiki Supper Club restaurant in Columbus. The food company now operates in the suburb of Gahanna and has been owned by the South Korean-based company CJ CheilJedang since 2018.[132] Wasserstrom Company, a major supplier of equipment and supplies for restaurants, is located on the north side.

Arts and culture

Landmarks

Columbus has over 170 notable buildings listed on the National Register of Historic Places; it also maintains its own register, the Columbus Register of Historic Properties, with 82 entries.[133] The city also maintains four historic districts not listed on its register: German Village, Italian Village, Victorian Village, and the Brewery District.[134]

Construction of the Ohio Statehouse began in 1839 on a 10-acre (4 ha) plot of land donated by four prominent Columbus landowners. This plot formed Capitol Square, which was not part of the city's original layout. Built of Columbus limestone from the Marble Cliff Quarry Co., the Statehouse stands on foundations 18 feet (5.5 m) deep that were laid by prison labor gangs rumored to have been composed largely of masons jailed for minor infractions.[38] It features a central recessed porch with a colonnade of a forthright and primitive Greek Doric mode. A broad and low central pediment supports the windowed astylar drum under an invisibly low saucer dome that lights the interior rotunda. There are several artworks within and outside the building, including the William McKinley Monument dedicated in 1907. Unlike many U.S. state capitol buildings, the Ohio State Capitol owes little to the architecture of the national Capitol. During the Statehouse's 22-year construction, seven architects were employed. The Statehouse was opened to the legislature and the public in 1857 and completed in 1861, and is located at the intersection of Broad and High streets in downtown Columbus.

Within the Driving Park heritage district lies the original home of Eddie Rickenbacker, a World War I fighter pilot ace. Built in 1895, the house was designated a National Historic Landmark in 1976.[135]

Demolitions and redevelopment

Demolition has been a common trend in Columbus for a long period of time, and continues into the present day. Preservationists and the public have sometimes run into conflict with developers hoping to revitalize an area, and historically with the city and state government, which led programs of urban renewal in the 20th century.[136]

Museums and public art

Columbus has a wide variety of museums and galleries. Its primary art museum is the Columbus Museum of Art, which operates its main location as well as the Pizzuti Collection, featuring contemporary art. The museum, founded in 1878, focuses on European and American art up to early modernism that includes extraordinary examples of Impressionism, German Expressionism and Cubism.[137] Another prominent art museum in the city is the Wexner Center for the Arts, a contemporary art gallery and research facility operated by the Ohio State University.

The Ohio History Connection is headquartered in Columbus, with its flagship museum, the 250,000-square-foot (23,000 m2) Ohio History Center, 4 mi (6.4 km) north of downtown. Adjacent to the museum is Ohio Village, a replica of a village around the time of the American Civil War. The Columbus Historical Society also features historical exhibits, which focus more closely on life in Columbus.

COSI is a large science and children's museum in downtown Columbus. The present building, the former Central High School, was completed in November 1999, opposite downtown on the west bank of the Scioto River. In 2009, Parents magazine named COSI one of the 10 best science centers for families in the country.[138] Other science museums include the Orton Geological Museum and the Museum of Biological Diversity, which are both part of Ohio State University.

The Franklin Park Conservatory is the city's botanical garden, which opened in 1895. It features over 400 species of plants in a large Victorian-style glass greenhouse building that includes rain forest, desert and Himalayan mountain biomes. The conservatory is located just east of Downtown in Franklin Park[139]

Biographical museums include the Thurber House (documenting the life of cartoonist James Thurber), the Jack Nicklaus Museum (documenting the golfer's career, located on the OSU campus) and the Kelton House Museum and Garden, the latter of which being a historic house museum memorializing three generations of the Kelton family, the house's use as a documented station on the Underground Railroad, and overall Victorian life.

The National Veterans Memorial and Museum, which opened in 2018, focuses on the personal stories of military veterans throughout U.S. history. The museum replaced the Franklin County Veterans Memorial, which opened in 1955.[140]

Other notable museums in the city include the Central Ohio Fire Museum, Billy Ireland Cartoon Library & Museum and the Ohio Craft Museum.

Performing arts

Columbus is the home of many performing arts institutions including the Columbus Symphony Orchestra, Opera Columbus, BalletMet Columbus, the ProMusica Chamber Orchestra, CATCO, Columbus Children's Theatre, Shadowbox Live, and the Columbus Jazz Orchestra. Throughout the summer, the Actors' Theatre of Columbus offers free performances of Shakespearean plays in an open-air amphitheater in Schiller Park in historic German Village.

The Columbus Youth Ballet Academy was founded in the 1980s by ballerina and artistic director Shir Lee Wu, a discovery of Martha Graham. Wu is now the artistic director of the Columbus City Ballet School.[141]

Columbus has several large concert venues, including the Nationwide Arena, Value City Arena, Express Live!, Mershon Auditorium and the Newport Music Hall.

In May 2009, the Lincoln Theatre, formerly a center for Black culture in Columbus, reopened after an extensive restoration.[142][143] Not far from the Lincoln Theatre is the King Arts Complex, which hosts a variety of cultural events. The city also has several theaters downtown, including the historic Palace Theatre, the Ohio Theatre and the Southern Theatre. Broadway Across America often presents touring Broadway musicals in these larger venues.[144] The Vern Riffe Center for Government and the Arts houses the Capitol Theatre and three smaller studio theaters, providing a home for resident performing arts companies.

Film

Movies filmed in the Columbus metropolitan area include Teachers in 1984, Tango & Cash in 1989, Little Man Tate in 1991, Air Force One in 1997, Traffic in 2000, Speak in 2004, Bubble in 2005, Liberal Arts in 2012, Parker in 2013, and I Am Wrath in 2016, Aftermath in 2017, They/Them/Us in 2021, and Bones and All in 2022.[145][146] The 2018 film Ready Player One is set in Columbus, though not filmed in the city.[147]

Sports

| Club | League | Sport | Venue (capacity) | Founded | Titles | Average Attendance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ohio State Buckeyes | NCAA | Football | Ohio Stadium (104,851) | 1890 | 8 | 105,261 |

| Columbus Crew | MLS | Soccer | Lower.com Field (20,371) | 1996 | 3 | 20,646 |

| Ohio State Buckeyes | NCAA | Basketball | Value City Arena (19,000) | 1892 | 1 | 16,511 |

| Columbus Blue Jackets | NHL | Ice hockey | Nationwide Arena (18,500) | 2000 | 0 | 16,659 |

| Columbus Clippers | IL | Baseball | Huntington Park (10,100) | 1977 | 11 | 9,212 |

| Columbus Crew 2 | MLS Next Pro | Soccer | Historic Crew Stadium (19,968) | 2022 | 1 | N/A |

Professional teams

Columbus hosts two major league professional sports teams: the Columbus Blue Jackets of the National Hockey League (NHL), which play at Nationwide Arena, and the Columbus Crew of Major League Soccer (MLS), which play at Lower.com Field. The Crew previously played at Historic Crew Stadium, the first soccer-specific stadium built in the United States for a Major League Soccer team. The Crew were one of the original members of MLS and won their first MLS Cup in 2008, a second title in 2020, and a third title in 2023. The Columbus Crew moved into Lower.com Field in the summer of 2021, which will also feature a mixed-use development site named Confluence Village.[149]

The Columbus Clippers, the International League affiliate of the Cleveland Guardians, play in Huntington Park, which opened in 2009.

The city was home to the Panhandles/Tigers football team from 1901 to 1926; they are credited with playing in the first NFL game against another NFL opponent.[150] In the late 1990s, the Columbus Quest won the only two championships during American Basketball League's two-and-a-half season existence.

The Ohio Aviators were based in Obetz, Ohio, and began play in the only PRO Rugby season before the league folded.[151]

Since 2023, Columbus has been home to the Columbus Fury women's professional volleyball team, one of seven teams to launch with the Pro Volleyball Federation.[152][153] The team plays home games at Nationwide Arena.[154]

Ohio State Buckeyes

Columbus is home to one of the nation's most competitive intercollegiate programs, the Ohio State Buckeyes of Ohio State University. The program has placed in the top 10 final standings of the Director's Cup five times since 2000–2001, including No. 3 for the 2002–2003 season and No. 4 for the 2003–2004 season.[155] The university funds 36 varsity teams, consisting of 17 male, 16 female and three co-educational teams.[156] In 2007–2008 and 2008–2009, the program generated the second-most revenue for college programs behind the Texas Longhorns of The University of Texas at Austin.[157][158]

The Ohio State Buckeyes are a member of the NCAA's Big Ten Conference, and their football team plays home games at Ohio Stadium. The Ohio State–Michigan football game (known colloquially as "The Game") is the final game of the regular season and is played in November each year, alternating between Columbus and Ann Arbor, Michigan. In 2000, ESPN ranked the Ohio State–Michigan game as the greatest rivalry in North American sports.[159] Moreover, "Buckeye fever" permeates Columbus culture year-round and forms a major part of Columbus's cultural identity. Former New York Yankees owner George Steinbrenner, an Ohio native who received a master's degree from Ohio State and coached in Columbus, was an Ohio State football fan and major donor to the university who contributed to the construction of the band facility at the renovated Ohio Stadium, which bears his family's name.[160] During the winter months, the Buckeyes basketball and hockey teams are also major sporting attractions.

Other sports

Columbus has a long history in motorsports, hosting the world's first 24-hour car race at the Columbus Driving Park in 1905, which was organized by the Columbus Auto Club.[161] The Columbus Motor Speedway was built in 1945 and held its first motorcycle race in 1946. In 2010, the Ohio State University student-built Buckeye Bullet 2, a fuel-cell vehicle, set an FIA world speed record for electric vehicles in reaching 303.025 mph, eclipsing the previous record of 302.877 mph.[162]

The annual All American Quarter Horse Congress, the world's largest single-breed horse show,[163] attracts approximately 500,000 visitors to the Ohio Expo Center each October.

Columbus hosts the annual Arnold Sports Festival. Hosted by Arnold Schwarzenegger, the event has grown to eight Olympic sports and 22,000 athletes competing in 80 events.[164]

Westside Barbell, a world-renowned powerlifting gym, is located in Columbus. Its founder, Louie Simmons, is known for his popularization of the "Conjugate Method," while he is also credited with inventing training machines for reverse hyper-extensions and belt squats. Westside Barbell is known for producing multiple world record holders in powerlifting.[165]

The Columbus Bullies were two-time champions of the American Football League (1940–1941). The Columbus Thunderbolts were formed in 1991 for the Arena Football League, and then relocated to Cleveland as the Cleveland Thunderbolts; the Columbus Destroyers were the next team of the AFL, playing from 2004 until the league's demise in 2008 and returned for single season in 2019 until the league folded a second time.

Ohio Roller Derby (formerly Ohio Roller Girls) was founded in Columbus in 2005 and still competes internationally in Women's Flat Track Derby Association play. The team is regularly ranked in the top 60 internationally.

Parks and attractions

Columbus's Recreation and Parks Department oversees about 370 city parks.[166] Also in the area are 19 regional parks and the Metro Parks, which are part of the Columbus and Franklin County Metropolitan Park District.

These parks include Clintonville's Whetstone Park and the Columbus Park of Roses, a 13-acre (5.3 ha) rose garden. The Chadwick Arboretum on Ohio State's campus features a large and varied collection of plants, while its Olentangy River Wetland Research Park is an experimental wetland open to the public. Downtown, the painting A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte is represented in topiary at Columbus's Topiary Park. Also near downtown, the Scioto Audubon Metro Park on the Whittier Peninsula opened in 2009 and includes a large Audubon nature center focused on the birdwatching the area is known for.[167]

The Columbus Zoo and Aquarium's collections include lowland gorillas, polar bears, manatees, Siberian tigers, cheetahs and kangaroos.[168] Also in the zoo complex is the Zoombezi Bay water park and amusement park.

Fairs and festivals

Annual festivities in Columbus include the Ohio State Fair – one of the largest state fairs in the country – as well as the Columbus Arts Festival and the Jazz & Rib Fest, both of which occur on the downtown riverfront.

In mid-May from 2007 to 2018, Columbus was home to Rock on the Range, which was held at Historic Crew Stadium and marketed as America's biggest rock festival. The festival, which took place on a Friday, Saturday and Sunday, has hosted Metallica, Red Hot Chili Peppers, Slipknot and other notable bands. In May 2019, it was officially replaced by the Sonic Temple Art & Music Festival.[169]

During the first weekend in June, the bars of Columbus's North Market District host the Park Street Festival, which attracts thousands of visitors to a massive party in bars and on the street. June's second-to-last weekend sees one of the Midwest's largest gay pride parades, Columbus Pride, reflecting the city's sizable gay population. During the last weekend of June, Goodale Park hosts ComFest (short for "Community Festival"), an immense three-day music festival marketed as the largest non-commercial festival in the U.S., with art vendors, live music on multiple stages, hundreds of local social and political organizations, body painting and beer.

The city's largest dining event, Restaurant Week Columbus, is held twice a year in mid-January and mid-July. In 2010, more than 40,000 diners went to 40 participating restaurants, and $5,000 (~$6,986 in 2023) was donated the Mid-Ohio Foodbank on behalf of sponsors and participating restaurants.[170]

Around the Fourth of July, Columbus hosts Red, White & Boom! on the Scioto riverfront downtown, attracting crowds of over 500,000 people and featuring the largest fireworks display in Ohio.[171]

The Short North is host to the monthly Gallery Hop, which attracts hundreds to the neighborhood's art galleries (which all open their doors to the public until late at night) and street musicians. The Hilltop Bean Dinner is an annual event held on Columbus's West Side that celebrates the city's Civil War heritage near the historic Camp Chase Cemetery. At the end of September, German Village throws an annual Oktoberfest celebration that features German food, beer, music and crafts.

Columbus also hosts many conventions in the Greater Columbus Convention Center, a large convention center on the north edge of downtown. Completed in 1993, the 1.8-million-square-foot (170,000 m2) convention center was designed by architect Peter Eisenman, who also designed the Wexner Center.[172]

Shopping

Both of the metropolitan area's major shopping centers are located in Columbus: Easton Town Center and Polaris Fashion Place.

Developer Richard E. Jacobs built the area's first three major shopping malls in the 1960s: Westland, Northland and Eastland.[173] Near Northland Mall was The Continent, an open-air mall in the Northland area, mostly vacant and pending redevelopment. Columbus City Center was built downtown in 1988, alongside the first location of Lazarus; this mall closed in 2009 and was demolished in 2011. Easton Town Center was built in 1999 and Polaris Fashion Place in 2001.

Environment

The City of Columbus has focused on reducing its environmental impact and carbon footprint. In 2020, a citywide ballot measure was approved, giving Columbus an electricity aggregation plan which will supply it with 100% renewable energy by the start of 2023. Its vendor, AEP Energy, plans to construct new wind and solar farms in Ohio to help supply the electricity.[174]

The largest sources of pollution in the county, as of 2019, are Ohio State University's McCracken Power Plant, the landfill operated by the Solid Waste Authority of Central Ohio (SWACO) and the Anheuser-Busch Columbus Brewery. Anheuser-Busch has a company-wide goal of reducing emissions by 25% by 2025. Ohio State plans to construct a new heat and power plant, also powered by fossil fuels, but set to reduce emissions by about 30%. SWACO manages to capture 75% of its methane emissions to use in producing energy, and is looking to reduce emissions further.[175]

Government

Mayor and city council

The city is administered by a mayor and a nine-member unicameral council elected in two classes every two years to four-year terms at large. Columbus is the largest city in the United States that elects its city council at large as opposed to districts. The mayor appoints the director of safety and the director of public service. The people elect the auditor, municipal court clerk, municipal court judges and city attorney. A charter commission, elected in 1913, submitted a new charter in May 1914, offering a modified federal form, with a number of progressive features, such as nonpartisan ballot, preferential voting, recall of elected officials, the referendum and a small council elected at large. The charter was adopted, effective January 1, 1916. Andrew Ginther has been the mayor of Columbus since 2016.[176]

Government offices

As Ohio's capital and the county seat, Columbus hosts numerous federal, state, county and city government offices and courts.

Federal offices include the Joseph P. Kinneary U.S. Courthouse,[177] one of several courts for the District Court for the Southern District of Ohio, after moving from 121 E. State St. in 1934. Another federal office, the John W. Bricker Federal Building, has offices for U.S. Senator Sherrod Brown, as well as for the Internal Revenue Service, the Social Security Administration and the Departments of Housing & Urban Development and Agriculture.[178]

The State of Ohio's capitol building, the Ohio Statehouse, is located in the center of downtown on Capitol Square. It houses the Ohio House of Representatives and Ohio Senate.[179] It also contains the ceremonial offices of the governor,[179] lieutenant governor, state treasurer[180] and state auditor.[181] The Supreme Court, Court of Claims and Judicial Conference are located in the Thomas J. Moyer Ohio Judicial Center downtown by the Scioto River. The building, built in 1933 to house 10 state agencies along with the State Library of Ohio, became the Supreme Court after extensive renovations from 2001 to 2004.[182]

Franklin County operates the Franklin County Government Center, a complex at the southern end of downtown Columbus. The center includes the county's municipal court, common pleas court, correctional center, juvenile detention center and sheriff's office.

Near City Hall, the Michael B. Coleman Government Center holds offices for the departments of building and zoning services, public service, development and public utilities. Also nearby is 77 North Front Street, which holds Columbus's city attorney office, income-tax division, public safety, human resources, civil service and purchasing departments. The structure, built in 1929, was the police headquarters until 1991, and was then dormant until it was given a $34 million renovation from 2011 to 2013.[183]

Emergency services and homeland security

Municipal police duties are performed by the Columbus Division of Police,[184] while emergency medical services (EMS) and fire protection are through the Columbus Division of Fire.

Ohio Homeland Security operates the Strategic Analysis and Information Center (SAIC) fusion center in Columbus's Hilltop neighborhood. The facility is the state's primary public intelligence hub and one of the few in the country that uses state, local, federal and private resources.[185][186]

Social services and homelessness

Columbus has a history of governmental and nonprofit support for low-income residents and the homeless. Nevertheless, the homelessness rate has steadily risen since at least 2007.[187] Poverty and differences in quality of life have grown, as well; Columbus was noted as the second-most economically segregated large metropolitan area in 2015, in a study by the University of Toronto.[188][189] It also ranked 45th of the 50 largest metropolitan areas in terms of social mobility, according to a 2015 Harvard University study.[190]

Education

Colleges and universities

Columbus is the home of two public colleges: the Ohio State University, one of the largest college campuses in the United States, and Columbus State Community College. In 2009, Ohio State University was ranked No. 19 in the country by U.S. News & World Report on its list of best public universities, and No. 56 overall, scoring in the first tier of schools nationally.[191] Some of Ohio State's graduate school programs placed in the top 5, including No. 5 for both best veterinary programs and best pharmacy programs. The specialty graduate programs of social psychology was ranked No. 2, dispute resolution was No. 5, vocational education was No. 2, and elementary education, secondary teacher education, administration/supervision was No. 5.[192]

Private institutions in Columbus include Capital University Law School, the Columbus College of Art and Design, Fortis College, DeVry University, Ohio Business College, Miami-Jacobs Career College, Ohio Institute of Health Careers, Bradford School and Franklin University, as well as the religious schools Bexley Hall Episcopal Seminary, Mount Carmel College of Nursing, Ohio Dominican University, Pontifical College Josephinum and Trinity Lutheran Seminary. Three major suburban schools also have an influence on Columbus's educational landscape: Bexley's Capital University, Westerville's Otterbein University and Delaware's Ohio Wesleyan University.

Primary and secondary schools

Columbus City Schools (CCS) is the largest district in Ohio, with 55,000 pupils.[193] CCS operates 142 elementary, middle and high schools, including a number of magnet schools (which are referred to as alternative schools within the school system).

The suburbs operate their own districts, typically serving students in one or more townships, with districts sometimes crossing municipal boundaries. The Roman Catholic Diocese of Columbus also operates several parochial elementary and high schools. The area's second-largest school district is South-Western City Schools, which encompasses southwestern Franklin County, including a slice of Columbus itself. Other portions of Columbus are zoned to the Dublin, Hilliard, New Albany-Plain, Westerville and Worthington school districts.

There are also several private schools in the area, such as St. Paul's Lutheran School, a K-8 Christian school of the Wisconsin Evangelical Lutheran Synod in Columbus.[194]

Some sources determine that the first kindergarten in the United States was established here by Louisa Frankenberg, a former student of Friedrich Fröbel.[43] Frankenberg immigrated to the city in 1838 and opened her kindergarten in the German Village neighborhood in that year. The school did not work out, so she returned to Germany in 1840. In 1858, Frankenberg returned to Columbus and established another early kindergarten in the city. Frankenberg is often overlooked, with Margarethe Schurz instead given credit for her "First Kindergarten" she operated for two years.[195]

In addition, Indianola Junior High School (now the Graham Elementary and Middle School) became the nation's first junior high school in 1909, helping to bridge the difficult transition from elementary to high school at a time when only 48% of students continued their education after the ninth grade.[196]

Libraries

The Columbus Metropolitan Library (CML) has served central Ohio residents since 1873. The system has 23 locations throughout Central Ohio, with a total collection of 3 million items. This library is one of the country's most-used library systems and is consistently among the top-ranked large city libraries according to Hennen's American Public Library Ratings. CML was rated the No. 1 library system in the nation in 1999, 2005 and 2008. It has been in the top four every year since 1999, when the rankings were first published in the American Libraries magazine, often challenging upstate neighbor Cuyahoga County Public Library for the top spot.[197][198]

Weekend education

The classes of the Columbus Japanese Language School, a weekend Japanese school, are held in a facility from the school district in Marysville, while the school office is in Worthington.[199] Previously it held classes at facilities in the city of Columbus.[200]

Media

Several weekly and daily newspapers serve Columbus and Central Ohio. The major daily newspaper in Columbus is The Columbus Dispatch. There are also neighborhood- or suburb-specific papers, such as the Dispatch Printing Company's ThisWeek Community News, the Columbus Messenger, the Clintonville Spotlight and the Short North Gazette. The Lantern and 1870 serve the Ohio State University community. Alternative arts, culture or politics-oriented papers include ALIVE (formerly the independent Columbus Alive and now owned by the Columbus Dispatch), Columbus Free Press and Columbus Underground (digital-only). The Columbus Magazine, CityScene, 614 Magazine and Columbus Monthly are the city's magazines.

Columbus is the base for 12 television stations and is the 32nd-largest television market as of September 24, 2016.[201] Columbus is also home to the 36th-largest radio market.[202]

Infrastructure

Healthcare

Numerous medical systems operate in Columbus and Central Ohio. These include OhioHealth, which has three hospitals in the city proper: Grant Medical Center, Riverside Methodist Hospital, and Doctors Hospital; Mount Carmel Health System, which has one hospital among other facilities; the Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center, which has a primary hospital complex and an east campus in Columbus;[203] and Nationwide Children's Hospital, which is an independently operated hospital for pediatric health care. Hospitals in Central Ohio are ranked favorably by the U.S. News & World Report, where numerous hospitals are ranked as among the best in particular fields in the United States. Nationwide Children's is regarded as among the top 10 children's hospitals in the country, according to the report.[204][205]

Utilities

Numerous utility companies operate in Central Ohio. Within Columbus, power is sourced from Columbus Southern Power, an American Electric Power subsidiary. Natural gas is provided by Columbia Gas of Ohio, while water is sourced from the City of Columbus Division of Water.[206]

Transportation

Local roads, grid and address system

The city's two main corridors since its founding are Broad and High Streets. They both traverse beyond the extent of the city; High Street is the longest in Columbus, running 13.5 mi (21.7 km) (23.4 across the county), while Broad Street is longer across the county, at 25.1 mi (40.4 km).[207]

The city's street plan originates downtown and extends into the old-growth neighborhoods, following a grid pattern with the intersection of High Street (running north–south) and Broad Street (running east–west) at its center. North–south streets run 12 degrees west of due north, parallel to High Street; the avenues (vis. Fifth Avenue, Sixth Avenue, Seventh Avenue, and so on) run 12 degrees off from east–west.[208][209]

The address system begins its numbering at the intersection of Broad and High, with numbers increasing in magnitude with distance from Broad or High, as well as cardinal directions used alongside street names.[210] Numbered avenues begin with First Avenue, about 1+1⁄4 mi (2.0 km) north of Broad Street, and increase in number as one progresses northward. Numbered streets begin with Second Street, which is two blocks west of High Street, and Third Street, which is a block east of High Street, then progress eastward from there. Even-numbered addresses are on the north and east sides of streets, putting odd addresses on the south and west sides of streets. A difference of 700 house numbers means a distance of about 1 mi (1.6 km) (along the same street).[77]

Other major, local roads in Columbus include Main Street, Morse Road, Dublin-Granville Road (SR-161), Cleveland Avenue/Westerville Road (SR-3), Olentangy River Road, Riverside Drive, Sunbury Road, Fifth Avenue and Livingston Avenue.

Highways

Columbus is bisected by two major Interstate Highways: Interstate 70 running east–west and Interstate 71 running north to roughly southwest. They combine downtown for about 1.5 mi (2.4 km) in an area locally known as "The Split", which is a major traffic congestion point, especially during rush hour. U.S. Route 40, originally known as the National Road, runs east–west through Columbus, comprising Main Street to the east of downtown and Broad Street to the west. U.S. Route 23 runs roughly north–south, while U.S. Route 33 runs northwest-to-southeast. The Interstate 270 Outerbelt encircles most of the city, while the newly redesigned Innerbelt consists of the Interstate 670 spur on the north side (which continues to the east past the Airport and to the west where it merges with I-70), State Route 315 on the west side, the I-70/71 split on the south side and I-71 on the east. Due to its central location within Ohio and abundance of outbound roadways, nearly all of the state's destinations are within a two- or three-hour drive of Columbus.

Bridges

The Columbus riverfront hosts several bridges. The Discovery Bridge connects downtown to Franklinton across Broad Street. The bridge opened in 1992, replacing a 1921 concrete arch bridge; the first bridge at the site was built in 1816.[211] The 700 ft (210 m) Main Street Bridge opened on July 30, 2010.[212] The bridge has three lanes for vehicular traffic (one westbound and two eastbound) and another separated lane for pedestrians and bikes. The Rich Street Bridge opened in July 2012 adjacent to the Main Street Bridge, connecting Rich Street on the east side of the river with Town Street on the west.[213][214] The Lane Avenue Bridge is a cable-stayed bridge that opened on November 14, 2003, in the University District. The bridge spans the Olentangy River with three lanes of traffic each way.

Airports

The city's primary airport, John Glenn Columbus International Airport, is on the city's east side. Formerly known as Port Columbus, John Glenn provides service to Toronto, Ontario, Canada, and Cancun, Mexico (on a seasonal basis), as well as to most domestic destinations, including all the major hubs along with San Francisco, Salt Lake City and Seattle. The airport was a hub for discount carrier Skybus Airlines and continues to be home to NetJets, the world's largest fractional ownership air carrier. According to a 2005 market survey, John Glenn Columbus International Airport attracts about 50% of its passengers from outside of its 60-mile (97 km) radius primary service region.[215] It is the 52nd-busiest airport in the United States by total passenger boardings.[216]

Rickenbacker International Airport, in southern Franklin County, is a major cargo facility that is used by the Ohio Air National Guard. Allegiant Air offers nonstop service from Rickenbacker to Florida destinations. Ohio State University Don Scott Airport and Bolton Field are other large general-aviation facilities in the Columbus area.

Aviation history

In 1907, 14-year-old Cromwell Dixon built the SkyCycle, a pedal-powered blimp, which he flew at Driving Park.[217] Three years later, one of the Wright brothers' exhibition pilots, Phillip Parmalee, conducted the world's first commercial cargo flight when he flew two packages containing 88 kilograms of silk 70 miles (110 km) from Dayton to Columbus in a Wright Model B.[218]

Military aviators from Columbus distinguished themselves during World War I. Six Columbus pilots, led by top ace Eddie Rickenbacker, achieved 42 "kills" – a full 10% of all US aerial victories in the war, and more than the aviators of any other American city.[219]

After the war, Port Columbus Airport (now known as John Glenn Columbus International Airport) became the axis of a coordinated rail-to-air transcontinental system that moved passengers from the East Coast to the West. TAT, which later became TWA, provided commercial service, following Charles Lindbergh's promotion of Columbus to the nation for such a hub. Following the failure of a bond levy in 1927 to build the airport, Lindbergh campaigned in the city in 1928, and the next bond levy passed that year.[217] On July 8, 1929, the airport opened for business with the inaugural TAT westbound flight from Columbus to Waynoka, Oklahoma. Among the 19 passengers on that flight was Amelia Earhart,[217] with Henry Ford and Harvey Firestone attending the opening ceremonies.[217]

In 1964, Ohio native Geraldine Fredritz Mock became the first woman to fly solo around the world, leaving from Columbus and piloting the Spirit of Columbus. Her flight lasted nearly a month and set a record for speed for planes under 3,858 pounds (1,750 kg).[220]

Public transit

Columbus maintains a widespread municipal bus service called the Central Ohio Transit Authority (COTA). The service operates 41 routes with a fleet of 440 buses, serving approximately 19 million passengers per year. COTA operates 23 regular fixed-service routes, 14 express services, a bus rapid transit route, a free downtown circulator, night service, an airport connector and other services.[221] LinkUS, an initiative between COTA, the city, and the Mid-Ohio Regional Planning Commission, is planning to add more rapid transit to Columbus, with three proposed corridors operating by 2030, and potentially a total of five by 2050.

Intercity bus service is provided at the Columbus Bus Station by Greyhound, Barons Bus Lines, Miller Transportation, GoBus and other carriers.[222]

Columbus does not have passenger rail service. The city's major train station, Union Station, was a stop along Amtrak's National Limited train service until 1977 and was razed in 1979,[223] and the Greater Columbus Convention Center now stands in its place. Until Amtrak's founding in 1971, the Penn Central ran the Cincinnati Limited to Cincinnati to the southwest (in prior years the train continued to New York City to the east); the Ohio State Limited between Cincinnati and Cleveland, with Union Station serving as a major intermediate stop (the train going unnamed between 1967 and 1971); and the Spirit of St. Louis, which ran between St. Louis and New York City until 1971. The station was also a stop along the Pennsylvania Railroad, the New York Central Railroad, the Chesapeake and Ohio Railway, the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad, the Norfolk and Western Railway, the Cleveland, Columbus and Cincinnati Railroad, and the Pittsburgh, Cincinnati, Chicago and St. Louis Railroad. As the city lacks local, commuter or intercity trains, Columbus is now the largest city and metropolitan area in the U.S. without any passenger rail service.[224][225] Numerous proposals to return rail service have been introduced; currently Amtrak plans to restore service to Columbus by 2035.

Cycling network

Cycling as transportation is steadily increasing in Columbus with its relatively flat terrain, intact urban neighborhoods, large student population and off-road bike paths. The city has put forth the 2012 Bicentennial Bikeways Plan, as well as a move toward a Complete Streets policy.[226][227] Grassroots efforts such as Bike to Work Week, Consider Biking, Yay Bikes,[228] Third Hand Bicycle Co-op,[229] Franklinton Cycleworks and Cranksters, a local radio program focused on urban cycling,[230] have contributed to cycling as transportation.

Columbus also hosts urban cycling "off-shots" with messenger-style "alleycat" races, as well as unorganized group rides, a monthly Critical Mass ride,[231] bicycle polo, art showings, movie nights and a variety of bicycle-friendly businesses and events throughout the year. All this activity occurs despite Columbus's frequently inclement weather.

The Main Street Bridge, opened in 2010, features a dedicated bike and pedestrian lane separated from traffic.