Agrawal

Maharaja Agrasen, the legendary king who was the forefather of Agrawals | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

|---|---|

| India, Pakistan, and Bangladesh | |

| Languages | |

| Punjabi, Haryanvi, Hindi, Rajasthani | |

| Religion | |

| Majority: Vaishnava Hinduism, Jainism, Sikhism Minority: Islam, Christianity[1][2] |

Agrawal (anglicisation: Agrawal, Agerwal, Agrawala, Agarwala, Agarwalla, Aggarwal, Agarawal, Agarawala, or Aggrawal) is a Bania caste.[3] The Banias of northern India are a cluster of several communities, of which the Agrawal Banias, Maheshwari Banias, Oswal Banias, Khatri Banias and Porwal Banias are a part.[4]

They are found throughout northern India, mainly in the states of Rajasthan, Haryana, Punjab, Jammu and Kashmir, Chandigarh, Himachal Pradesh, Uttarakhand, Delhi, Chhattisgarh, Gujarat, Maharashtra and Uttar Pradesh. They are also found in the Pakistani provinces of Punjab and Sindh, though at the time of the partition of India, most of them migrated across the newly created border to independent India.[5][6][7] Most Agrawals follow Vaishnava Hinduism or Jainism, while a minority adhere to Islam or Christianity.[1][8][2]

The Agrawal believe the ancestor of the community to be Maharaja Agrasen, a Kshatriya king of Agroha Kingdom.[9] Maharaja Agrasen himself adopted the Vaishya tradition of Hinduism.[9] The Agrawal are also known for the entrepreneurship and business acumen.[9] In modern-day tech and ecommerce companies, they continue to dominate. It was reported in 2013, that for every 100 in funding for e-commerce companies in India, 40 went to firms founded by Agrawals.[10]

History

[edit]Agrawals are one of the Bania (merchant) communities in India, which includes other mercantile communities like Maheshwari, and Oswals.[12][13]

In inscriptions and texts, the original home of the Agrawal community is stated as Agroha, near Hisar, Haryana.

- In Pradumna Charita of samvat 1411 (1354 AD), the Agrawal poet Sadharu wrote "अग्रवाल की मेरी जात, पुर अग्रोहा महि उतपात" ("My jāti is Agrawal, and I trace my roots to the city of Agroha).[14]

- In his Padma Purana[15] of VS 1711 (AD 1654), Muni Sabhachandra writes "अग्रोहे निकट प्रभु ठाढे जोग, करैं वन्दना सब ही लोग|| अग्रवाल श्रावक प्रतिबोध, त्रेपन क्रिया बताई सोध||", (When Lohacharya was near Agroha, he taught the 53 actions to the Agrawal shravakas).

- In a Sanskrit inscription, the Agrawals are referred to as Agrotaka ("from Agroha"). A 1272 AD inscription states: "सं १३२९ चैत्र वुदी दशम्यां बुधवासरे अद्येह योगिनिपुरे समस्त राजावलि-समलन्कृत ग्यासदीन राज्ये अत्रस्थित अग्रोतक परम श्रावक जिनचरणकमल".[16]

Some of the Agrawals adapted Jainism under the influence of Lohacharya.[17]

Migration to Delhi

[edit]The Agrawal merchant Nattal Sahu, and the Agrawal poet, Vibudh Shridhar, lived during the reign of Tomara King Anangapal of Yoginipur (now Mehrauli, near Delhi).[18] Vibudh Shridhar wrote Pasanahacariu in 1132 AD, which includes a historical account of Yoginipur (early Delhi near Mehrauli) then.

In 1354, Firuz Shah Tughluq had started the construction of a new city near Agroha, called Hisar-e-Feroza ("the fort of Firuz"). Most of the raw material for building the town was brought from Agroha.[19] The town later came to be called Hisar. Hisar became a major center of the Agrawal community. Some Agrawals are also said to have moved to the Kotla Firoz Shah fort in Delhi, built by Firuz Shah Tughlaq.

Migration to Rajput kingdoms

[edit]During the era of Islamic administrative rule in India, some Agrawal, as with the Saraogi, migrated to the Bikaner State.[citation needed] The Malkana include Muslim Agrawals, who converted from Hinduism to Islam during this time and were given land tracts along the Yamuna by Afghan rulers.[2]

In the early 15th century, Agrawals flourished under the Tomaras of Gwalior.[20][full citation needed] According to several Sanskrit inscription at the Gwalior Fort in Gwalior District, several traders (Sanghavi Kamala Simha, Khela Brahmachari, Sandhadhip Namadas etc.) belonging to Agrotavansha (Agrawal clan) supported the sculptures and carving of idols at the place.[21] Historian K.C. Jain comments:

Golden Age of the Jain Digambar Temple in Gwalior under the Tomara rulers inspired by the Kashtha Bhattarakas and their Jaina Agrawal disciples who dominated the Court of father and son viz. Dungar Singh (1425-59)and Kirti Singh (1459–80) with the Poet-Laureate Raighu as their mouthpiece and spokesman, a centenarian author of as many as thirty books, big and small of which two dozen are reported to be extant today. Verify the advent of the Hisar-Firuza-based Jain Agrawals who functioned as the ministers and treasurers of the ruling family had turned the Rajput State of Gwalior into a Digambara Jain Centre par excellence representing the culture of the Agrawal multi-millionner shravakas as sponsored by them.[20]

Migration to Eastern India

[edit]Later, during the Mughal rule, and during the British East India Company administration, some Agrawals migrated to Bihar and Calcutta, who became the major component of the Marwaris.[22][page needed]

Gotras

[edit]Agrawals belong to various gotras, traditionally said to be seventeen and a half in number. According to Bharatendu Harishchandra's Agrawalon ki Utpatti (1871), Agrasen - the legendary progenitor of the community - performed 17 sacrifices and left the eighteenth incomplete, resulting in this number. Bharatendu also mentions that Agrasen had 17 queens and a junior queen, but does not mention any connection between the number of gotras and the number of queens, or describe how the sacrifices led to the formation of the gotras.[23] Another popular legend claims that a boy and girl from the Goyan gotra married each other by mistake, which led to the formation of a new "half" gotra. Another popular belief that since Maharaj Agrasen has 17 son and one daughter so where his daughter was married the gotra of daughter in laws were adopted as half gotra in Agrawals, thus 17.5 gotra. [24]

Historically, there has been no unanimity regarding number and names of these seventeen and a half gotras, and there are regional differences between the list of gotras. The Akhil Bhartiya Agrawal Sammelan, a major organization of Agrawals, has created a standardized list of gotras, which was adopted as an official list by a vote at the organization's 1983 convention.[25] Because the classification of any particular gotra as "half" is considered insulting, the Sammelan provides a list of following 18 gotras:[26]

The existence of all the gotras mentioned in the list is controversial, and the list does not include several existing clans such as Kotrivala, Pasari, Mudgal, Tibreval, and Singhla.[27][need quotation to verify]

Notable Agrawals

[edit]See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b Harrison, Selig S. (8 December 2015). India: The Most Dangerous Decades. Princeton University Press. p. 115. ISBN 978-1-4008-7780-5.

Some subsects of the Oswals and Agarwals were converted to Jainism in the 16th century.

- ^ a b c Sikand, Yoginder; Katju, Manjari (20 August 1994). "Mass Conversions to Hinduism among Indian Muslims". Economic and Political Weekly. 29 (34): 2214–2219.

- ^ Patel, Aakar (6 February 2015). "A history of the Agarwals". mint. Retrieved 5 April 2024.

- ^ "A history of the Agarwal's". 6 February 2015.

- ^ Gupta, Babu Lal (1987). Trade and Commerce in Rajasthan During the 18th Century. Jaipur Publishing House. p. 88.

- ^ Das, Sibir Ranjan (2012). Resilience and Identity in Urban India: Anthropology of Barmer and Tehri. Anthropological Survey of India. p. 107. ISBN 978-81-922974-9-1.

- ^ Gulzar Ahmed Chaudhry (4 June 2014). "Nagar Mahal – from Agarwals to Sukheras". Dawn. Pakistan.

- ^ Goh, Robbie B. H. (8 February 2018). Protestant Christianity in the Indian Diaspora: Abjected Identities, Evangelical Relations, and Pentecostal Visions. SUNY Press. ISBN 978-1-4384-6944-7.

Agarwal recounts how the news of his own conversion was greeted by his grandmother in Punjab...

- ^ a b c Jodhka, Surinder S. (2023). The Oxford Handbook of Caste. Oxford University Press. p. 393. ISBN 978-0-19-889671-5.

- ^ Julka, Harsimran; Radhika P. Nair (12 February 2013). "Why young Aggarwals dominate India's e-commerce start-ups". The Economic Times. Delhi. Archived from the original on 16 February 2013.

- ^ Down to Earth: Science and Environment Fortnightly, Volume 16, Issues 16-24. Society for Environmental Communications. 2008. p. 71.

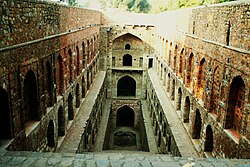

Resembling Tughlak period architectures, it was probably constructed by the Agrawal community (tracing back to Maharaja Agrasen).

- ^ Hanks, Patrick (8 May 2003). Dictionary of American Family Names. Oxford University Press. p. xcvi. ISBN 978-0-19-977169-1.

The Banias of northern India are really a cluster of several communities, of which the Agarwal Banias, Oswal Banias, and Porwal Banias are mentioned separately in connection with certain surnames.

- ^ Harishchandra, Bharatendu (23 October 2020). Agarwalon ki utpatti (in Hindi). खेमराज श्रीकृष्णदास अध्यक्ष : श्रीवेंकटेश्वर प्रेस, ९१/१०९, खेमराज श्रीकृष्णदास मार्ग, ७ वी खेतवाडी बैंक रोड कार्नर, मुंबई - ४०० ००४. दूरभाष/फैक्स-०२२-२३८५७४५६. खेमराज श्रीकृष्णदास ६६, हडपसर इण्डस्ट्रियल इस्टेट, पुणे - ४११०१३. दूरभाष-०२०-२६८७१०२५, फेक्स -०२०-२६८७४१०७. गंगाविष्णु श्रीकृष्णदास, लक्ष्मी वेंकटेश्वर प्रेस व बुक डिपो श्रीलक्ष्मीवेंकटेश्वर प्रेस बिल्डींग, जूना छापाखाना गली, अहिल्याबाई चौक, कल्याण, बि. ठाणे, महाराष्ट्र - ४२१ ३०१ दूरभाष/फेक्स-०२५१-२२०९०६१. खेमराज श्रीकृष्णदास चौक, वाराणसी (उ.प्र.) २२१ ००१. दूरभाष - ०५४२-२४२००७८.: bharatenduHarichandra.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - ^ Dr. Kasturachand Kasliwal, Khandelwal Jain Samaj ka Vrihad Itihas, 1969, p. 49

- ^ Muni Sabhachandra aur Unaka Padmapurana, Kasturchanda Kasliwal, 1984

- ^ Parmananda Jain Shastri. Agrawalon ka Jain sanskriti mein yogadan. Anekanta Oct. 1966, p. 277-281

- ^ Singh, K. S. (2008). People of India: Bihar. Anthropological Survey of India. p. 46. ISBN 978-81-85579-09-2.

The bulk of the Agrawals belong to Vaishnava sect of Hinduism. ... Agrawals, it is believed, were converted to Jainism by Sri Loha Charyaji between 27 and 77 years of the Vikram era.

- ^ An Early Attestation of the Toponym Ḍhillī, by Richard J. Cohen, Journal of the American Oriental Society, 1989, p. 513-519

- ^ The story of Hisar

- ^ a b Kashtha Sangha Bhattarakas of Gwalior and Agrawal Shravakas, Dr. K. C. Jain, 1963, p. 72

- ^ "गोपाचल के जिन मन्दिर एवं प्रतिमाएँ" (in Hindi). Webdunia.com. Archived from the original on 24 December 2004. Retrieved 2 June 2007.

- ^ Hardgrove, Anne (2004). Community and Public Culture: The Marwaris in Calcutta, c. 1897–1997. Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-23112-216-0.

- ^ Lawrence A. Babb 2004, pp. 201–202.

- ^ M. S. Gore 1990, p. 69.

- ^ Lawrence A. Babb 2004, pp. 193–194.

- ^ Lawrence A. Babb 2004, p. 192.

- ^ Lawrence A. Babb 2004, p. 193.

Bibliography

[edit]- Lawrence A. Babb (2004). Alchemies of Violence: Myths of Identity and the Life of Trade in Western India. SAGE. ISBN 978-0-7619-3223-9.

- M. S. Gore (1990). Urbanization and Family Change. Popular Prakashan. ISBN 978-0-86132-262-6.

External links

[edit] Media related to Agrawal at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Agrawal at Wikimedia Commons

- Agrawal

- Bania communities

- Social groups of Rajasthan

- Social groups of Haryana

- Social groups of Delhi

- Social groups of Uttar Pradesh

- Social groups of Punjab, India

- Social groups of Himachal Pradesh

- Social groups of Uttarakhand

- Surnames of Hindu origin

- People from Hisar district

- Surnames of Hindustani origin

- Surnames of Indian origin

- Aggarwal