Glyphosate

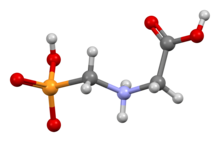

Idealised skeletal formula of the uncharged molecule

| |

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| Pronunciation | /ˈɡlɪfəseɪt, ˈɡlaɪfə-/,[3] /ɡlaɪˈfɒseɪt/[4][5] |

| IUPAC name

N-(Phosphonomethyl)glycine

| |

| Systematic IUPAC name

[(Phosphonomethyl)amino]acetic acid | |

| Identifiers | |

| |

3D model (JSmol)

|

|

| 2045054 | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| ChemSpider | |

| DrugBank | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.012.726 |

| EC Number |

|

| 279222 | |

| KEGG | |

PubChem CID

|

|

| RTECS number |

|

| UNII | |

| UN number | 3077 2783 |

CompTox Dashboard (EPA)

|

|

| |

| |

| Properties[6] | |

| C3H8NO5P | |

| Molar mass | 169.073 g·mol−1 |

| Appearance | white crystalline powder |

| Density | 1.704 (20 °C) |

| Melting point | 184.5 °C (364.1 °F; 457.6 K) |

| Boiling point | 187 °C (369 °F; 460 K) decomposes |

| 1.01 g/100 mL (20 °C) | |

| log P | −2.8 |

| Acidity (pKa) | <2, 2.6, 5.6, 10.6 |

| Hazards[6][7] | |

| GHS labelling: | |

| |

| Danger | |

| H318, H411 | |

| P273, P280, P305+P351+P338, P310, P501 | |

| Flash point | Non-flammable |

| Safety data sheet (SDS) | InChem MSDS |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

| |

Glyphosate (IUPAC name: N-(phosphonomethyl)glycine) is a broad-spectrum systemic herbicide and crop desiccant. It is an organophosphorus compound, specifically a phosphonate, which acts by inhibiting the plant enzyme 5-enolpyruvylshikimate-3-phosphate synthase (EPSP). Glyphosate-based herbicides are used to kill weeds, especially annual broadleaf weeds and grasses that compete with crops. Its herbicidal effectiveness was discovered by Monsanto chemist John E. Franz in 1970. Monsanto brought it to market for agricultural use in 1974 under the trade name Roundup. Monsanto's last commercially relevant United States patent expired in 2000.

Farmers quickly adopted glyphosate for agricultural weed control, especially after Monsanto introduced glyphosate-resistant Roundup Ready crops, enabling farmers to kill weeds without killing their crops. In 2007, glyphosate was the most used herbicide in the United States' agricultural sector and the second-most used (after 2,4-D) in home and garden, government and industry, and commercial applications.[8] From the late 1970s to 2016, there was a 100-fold increase in the frequency and volume of application of glyphosate-based herbicides (GBHs) worldwide, with further increases expected in the future.

Glyphosate is absorbed through foliage, and minimally through roots, and from there translocated to growing points. It inhibits EPSP synthase, a plant enzyme involved in the synthesis of three aromatic amino acids: tyrosine, tryptophan, and phenylalanine. It is therefore effective only on actively growing plants and is not effective as a pre-emergence herbicide. Crops have been genetically engineered to be tolerant of glyphosate (e.g. Roundup Ready soybean, the first Roundup Ready crop, also created by Monsanto), which allows farmers to use glyphosate as a post-emergence herbicide against weeds.

While glyphosate and formulations such as Roundup have been approved by regulatory bodies worldwide, concerns about their effects on humans and the environment have persisted.[9][10] A number of regulatory and scholarly reviews have evaluated the relative toxicity of glyphosate as an herbicide. The WHO and FAO Joint committee on pesticide residues issued a report in 2016 stating the use of glyphosate formulations does not necessarily constitute a health risk, and giving an acceptable daily intake limit of 1 milligram per kilogram of body weight per day for chronic toxicity.[11]

The consensus among national pesticide regulatory agencies and scientific organizations is that labeled uses of glyphosate have demonstrated no evidence of human carcinogenicity.[12] In March 2015, the World Health Organization's International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) classified glyphosate as "probably carcinogenic in humans" (category 2A) based on epidemiological studies, animal studies, and in vitro studies.[10][13][14][15] In contrast, the European Food Safety Authority concluded in November 2015 that "the substance is unlikely to be genotoxic (i.e. damaging to DNA) or to pose a carcinogenic threat to humans", later clarifying that while carcinogenic glyphosate-containing formulations may exist, studies that "look solely at the active substance glyphosate do not show this effect".[16][17] In 2017, the European Chemicals Agency (ECHA) classified glyphosate as causing serious eye damage and as toxic to aquatic life but did not find evidence implicating it as a carcinogen, a mutagen, toxic to reproduction, nor toxic to specific organs.[18]

Discovery

Glyphosate was first synthesized in 1950 by Swiss chemist Henry Martin, who worked for the Swiss company Cilag. The work was never published.[19]: 1 Early studies found it to be a weak chemical chelating agent.[20][21]

Somewhat later, glyphosate was independently discovered in the United States at Monsanto in 1970. Monsanto chemists had synthesized about 100 derivatives of aminomethylphosphonic acid as potential water-softening agents. Two were found to have weak herbicidal activity, and John E. Franz, a chemist at Monsanto, was asked to try to make analogs with stronger herbicidal activity. Glyphosate was the third analog he made.[19]: 1–2 [22][23] Franz received the National Medal of Technology of the United States in 1987 and the Perkin Medal for Applied Chemistry in 1990 for his discoveries.[24][25][26]

Monsanto developed and patented the use of glyphosate to kill weeds in the early 1970s and first brought it to market in 1974, under the Roundup brandname.[27][28] While its initial patent[29] expired in 1991, Monsanto retained exclusive rights in the United States until its patent[30] on the isopropylamine salt expired in September 2000.[31]

In 2008, United States Department of Agriculture Agricultural Research Service (USDA ARS) scientist Stephen O. Duke and Stephen B. Powles – an Australian weed expert – described glyphosate as a "virtually ideal" herbicide.[27] In 2010 Powles stated: "glyphosate is a one in a 100-year discovery that is as important for reliable global food production as penicillin is for battling disease."[32]

As of April 2017, the Canadian government stated that glyphosate was "the most widely used herbicide in Canada",[33] at which date the product labels were revised to ensure a limit of 20% POEA by weight.[33][failed verification] Health Canada's Pest Management Regulatory Agency found no risk to humans or the environment at that 20% limit, and that all products registered in Canada at that time were at or below that limit.

Chemistry

Glyphosate is an aminophosphonic analogue of the natural amino acid glycine and, like all amino acids, exists in different ionic states depending on pH. Both the phosphonic acid and carboxylic acid moieties can be ionised and the amine group can be protonated and the substance exists as a series of zwitterions. Glyphosate is soluble in water to 12 g/L at room temperature. The original synthetic approach to glyphosate involved the reaction of phosphorus trichloride with formaldehyde followed by hydrolysis to yield a phosphonate. Glycine is then reacted with this phosphonate to yield glyphosate, and its name is taken as a contraction of the compounds used in this synthesis step, namely glycine and a phosphonate.[34]

- PCl3 + H2CO → Cl2P(=O)−CH2Cl

- Cl2P(=O)−CH2Cl + 2 H2O → (HO)2P(=O)−CH2Cl + 2 HCl

- (HO)2P(=O)−CH2Cl + H2N−CH2−COOH → (HO)2P(=O)−CH2−NH−CH2−COOH + HCl

The main deactivation path for glyphosate is hydrolysis to aminomethylphosphonic acid.[35]

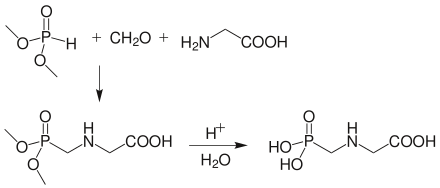

Synthesis

Two main approaches are used to synthesize glyphosate industrially, both of which proceed via the Kabachnik–Fields reaction. The first is to react iminodiacetic acid and formaldehyde with phosphorous acid (sometimes formed in situ from phosphorus trichloride using the water generated by the Mannich reaction of the first two reagents). Decarboxylation of the hydrophosphonylation product gives the desired glyphosate product. Iminodiacetic acid is usually prepared on-site by various methods depending on reagent availability.[19]

The second uses glycine in place of iminodiacetic acid. This avoids the need for decarboxylation but requires more careful control of stoichiometry, as the primary amine can react with any excess formaldehyde to form bishydroxymethylglycine, which must be hydrolysed during the work-up to give the desired product.[19]

This synthetic approach is responsible for a substantial portion of the production of glyphosate in China, with considerable work having gone into recycling the triethylamine and methanol solvents.[19] Progress has also been made in attempting to eliminate the need for triethylamine altogether.[36]

Impurities

Technical grade glyphosate is a white powder which, according to FAO specification, should contain not less than 95% glyphosate. Formaldehyde, classified as a known human carcinogen, [37] [38] and N-nitrosoglyphosate, have been identified as toxicologically relevant impurities.[39] The FAO specification limits the formaldehyde concentration to a maximum of 1.3 g/kg glyphosate. N-Nitrosoglyphosate, "belonging to a group of impurities of particular concern as they can be activated to genotoxic carcinogens",[40] should not exceed 1 ppm.[39]

Formulations

Glyphosate is marketed in the United States and worldwide by many agrochemical companies, in different solution strengths and with various adjuvants, under dozens of tradenames.[41][42][43][44] As of 2010, more than 750 glyphosate products were on the market.[45] In 2012, about half of the total global consumption of glyphosate by volume was for agricultural crops,[46] with forestry comprising another important market.[47] Asia and the Pacific was the largest and fastest growing regional market.[46] As of 2014, Chinese manufacturers collectively are the world's largest producers of glyphosate and its precursors[48] and account for about 30% of global exports.[46] Key manufacturers include Anhui Huaxing Chemical Industry Company, BASF, Bayer CropScience (which also acquired the maker of glyphosate, Monsanto), Dow AgroSciences, DuPont, Jiangsu Good Harvest-Weien Agrochemical Company, Nantong Jiangshan Agrochemical & Chemicals Co., Nufarm, SinoHarvest, Syngenta, and Zhejiang Xinan Chemical Industrial Group Company.[46]

Glyphosate is an acid molecule, so it is formulated as a salt for packaging and handling. Various salt formulations include isopropylamine, diammonium, monoammonium, or potassium as the counterion. The active ingredient of the Monsanto herbicides is the isopropylamine salt of glyphosate. Another important ingredient in some formulations is the surfactant polyethoxylated tallow amine (POEA). Some brands include more than one salt. Some companies report their product as acid equivalent (ae) of glyphosate acid, or some report it as active ingredient (ai) of glyphosate plus the salt, and others report both. To compare performance of different formulations, knowledge of how the products were formulated is needed. Given that different salts have different weights, the acid equivalent is a more accurate method of expressing and comparing concentrations.

Adjuvant loading refers to the amount of adjuvant[49][50] already added to the glyphosate product. Fully loaded products contain all the necessary adjuvants, including surfactant; some contain no adjuvant system, while other products contain only a limited amount of adjuvant (minimal or partial loading) and additional surfactants must be added to the spray tank before application.[51]

Products are supplied most commonly in formulations of 120, 240, 360, 480, and 680 g/L of active ingredient. The most common formulation in agriculture is 360 g/L, either alone or with added cationic surfactants.[42]

For 360 grams per litre (0.013 lb/cu in) formulations, European regulations allow applications of up to 12 litres per hectare (1.1 imp gal/acre) for control of perennial weeds such as couch grass. More commonly, rates of 3 litres per hectare (0.27 imp gal/acre) are practiced for control of annual weeds between crops.[52]

Mode of action

Glyphosate interferes with the shikimate pathway, which produces the aromatic amino acids phenylalanine, tyrosine and tryptophan in plants and microorganisms[53] – but does not exist in the genome of animals, including humans.[54][20] It blocks this pathway by inhibiting the enzyme 5-enolpyruvylshikimate-3-phosphate synthase (EPSPS), which catalyzes the reaction of shikimate-3-phosphate (S3P) and phosphoenolpyruvate to form 5-enolpyruvyl-shikimate-3-phosphate (EPSP).[55] Glyphosate is absorbed through foliage and minimally through roots, meaning that it is only effective on actively growing plants and cannot prevent seeds from germinating.[56][57] After application, glyphosate is readily transported around the plant to growing roots and leaves and this systemic activity is important for its effectiveness.[27][19] Inhibiting the enzyme causes shikimate to accumulate in plant tissues and diverts energy and resources away from other processes, eventually killing the plant. While growth stops within hours of application, it takes several days for the leaves to begin turning yellow.[58] Glyphosate may chelate Co2+ which contributes to its mode of action.[59][60][61]

Under normal circumstances, EPSP is dephosphorylated to chorismate, an essential precursor for the amino acids mentioned above.[62] These amino acids are used in protein synthesis and to produce secondary metabolites such as folates, ubiquinones, and naphthoquinone.

X-ray crystallographic studies of glyphosate and EPSPS show that glyphosate functions by occupying the binding site of the phosphoenolpyruvate, mimicking an intermediate state of the ternary enzyme–substrate complex.[63][64] Glyphosate inhibits the EPSPS enzymes of different species of plants and microbes at different rates.[65][66]

Uses

Glyphosate is effective in killing a wide variety of plants, including grasses and broadleaf and woody plants. By volume, it is one of the most widely used herbicides.[56] In 2007, glyphosate was the most used herbicide in the United States agricultural sector, with 180 to 185 million pounds (82,000 to 84,000 tonnes) applied, the second-most used in home and garden with 5 to 8 million pounds (2,300 to 3,600 tonnes) and 13 to 15 million pounds (5,900 to 6,800 tonnes) in non-agricultural settings.[8] It is commonly used for agriculture, horticulture, viticulture, and silviculture purposes, as well as garden maintenance (including home use). It has a relatively small effect on some clover species and morning glory.[67]

Glyphosate and related herbicides are often used in invasive species eradication and habitat restoration, especially to enhance native plant establishment in prairie ecosystems. The controlled application is usually combined with a selective herbicide and traditional methods of weed eradication such as mulching to achieve an optimal effect.[68]

In many cities, glyphosate is sprayed along the sidewalks and streets, as well as crevices in between pavement where weeds often grow. However, up to 24% of glyphosate applied to hard surfaces can be run off by water.[69] Glyphosate contamination of surface water is attributed to urban and agricultural use.[70] Glyphosate is used to clear railroad tracks and get rid of unwanted aquatic vegetation.[57] Since 1994, glyphosate has been used in aerial spraying in Colombia in coca eradication programs; Colombia announced in May 2015 that by October, it would cease using glyphosate in these programs due to concerns about human toxicity of the chemical.[71]

Glyphosate is also used for crop desiccation to increase harvest yield and uniformity.[57] Glyphosate itself is not a chemical desiccant; rather crop desiccants are so named because application just before harvest kills the crop plants so that the food crop dries from normal environmental conditions ("dry-down") more quickly and evenly.[72][74] Because glyphosate is systemic, excess residue levels can persist in plants due to incorrect application and this may render the crop unfit for sale.[75] When applied appropriately, it can promote useful effects. In sugarcane, for example, glyphosate application increases sucrose concentration before harvest.[76] In grain crops (wheat, barley, oats), uniformly dried crops do not have to be windrowed (swathed and dried) prior to harvest, but can easily be straight-cut and harvested. This saves the farmer time and money, which is important in northern regions where the growing season is short, and it enhances grain storage when the grain has a lower and more uniform moisture content.[57][77][78]

Genetically modified crops

Some micro-organisms have a version of 5-enolpyruvoyl-shikimate-3-phosphate synthetase (EPSPS) resistant to glyphosate inhibition. A version of the enzyme that was both resistant to glyphosate and that was still efficient enough to drive adequate plant growth was identified by Monsanto scientists after much trial and error in an Agrobacterium strain called CP4, which was found surviving in a waste-fed column at a glyphosate production facility.[66][79][80]: 56 This CP4 EPSPS gene was cloned and transfected into soybeans. In 1996, genetically modified soybeans were made commercially available.[81] Current glyphosate-resistant crops include soy, maize (corn), canola, alfalfa, sugar beets, and cotton, with wheat still under development.

In 2023, 91% of corn, 95% of soybeans, and 94% of cotton produced in the United States were from strains that were genetically modified to be tolerant to multiple herbicides, including dicamba, glufosinate, and glyphosate.[82]

Environmental fate

Glyphosate has four ionizable sites, with pKa values of 2.0, 2.6, 5.6 and 10.6.[83] Therefore, it is a zwitterion in aqueous solutions and is expected to exist almost entirely in zwitterionic forms in the environment. Zwitterions generally adsorb more strongly to soils containing organic carbon and clay than their neutral counterparts.[84] Glyphosate strongly sorbs onto soil minerals, and, with the exception of colloid-facilitated transport, its soluble residues are expected to be poorly mobile in the free porewater of soils. The spatial extent of ground and surface water pollution is therefore considered to be relatively limited.[85] Glyphosate is readily degraded by soil microbes to aminomethylphosphonic acid (AMPA, which like glyphosate strongly adsorbs to soil solids and is thus unlikely to leach to groundwater). Though both glyphosate and AMPA are commonly detected in water bodies, a portion of the AMPA detected may actually be the result of degradation of detergents and other aminophosphonates rather than degradation of glyphosate.[86] The proportion of AMPA from non-glyphosate sources is claimed to be higher in Europe compared to USA.[87] Glyphosate does have the potential to contaminate surface waters due to its aquatic use patterns and through erosion, as it adsorbs to colloidal soil particles suspended in runoff. Detection in surface waters (particularly downstream from agricultural uses) has been reported as both broad and frequent by the United States Geological Survey (USGS) researchers,[88] although other similar research found equal frequencies of detection in urban-dominated small streams.[89] Rain events can trigger dissolved glyphosate loss in transport-prone soils.[90] The mechanism of glyphosate sorption to soil is similar to that of phosphate fertilizers, the presence of which can reduce glyphosate sorption.[91] Phosphate fertilizers are subject to release from sediments into water bodies under anaerobic conditions, and similar release can also occur with glyphosate, though significant impact of glyphosate release from sediments has not been established.[92] Limited leaching can occur after high rainfall after application. If glyphosate reaches surface water, it is not broken down readily by water or sunlight.[93][85]

The half-life of glyphosate in soil ranges between 2 and 197 days; a typical field half-life of 47 days has been suggested. Soil and climate conditions affect glyphosate's persistence in soil. The median half-life of glyphosate in water varies from a few to 91 days.[56] At a site in Texas, half-life was as little as three days. A site in Iowa had a half-life of 141.9 days.[94] The glyphosate metabolite AMPA has been found in Swedish forest soils up to two years after a glyphosate application. In this case, the persistence of AMPA was attributed to the soil being frozen for most of the year.[95] Glyphosate adsorption to soil, and later release from soil, varies depending on the kind of soil.[96][97] Glyphosate is generally less persistent in water than in soil, with 12- to 60-day persistence observed in Canadian ponds, although persistence of over a year has been recorded in the sediments of American ponds.[93] The half-life of glyphosate in water is between 12 days and 10 weeks.[98]

Residues in food products

According to the National Pesticide Information Center fact sheet, glyphosate is not included in compounds tested for by the Food and Drug Administration's Pesticide Residue Monitoring Program, nor in the United States Department of Agriculture's Pesticide Data Program.[56] The U.S. has determined the acceptable daily intake of glyphosate at 1.75 milligrams per kilogram of body weight per day (mg/kg/bw/day) while the European Union has set it at 0.5.[99]

Pesticide residue controls carried out by EU Member States in 2016 analysed 6,761 samples of food products for glyphosate residues. 3.6% of the samples contained quantifiable glyphosate residue levels with 19 samples (0.28%) exceeding the European maximum residue levels (MRLs), which included six samples of honey and other apicultural products (MRL = 0.05 mg/kg) and eleven samples of buckwheat and other pseudo‐cereals (MRL = 0.1 mg/kg). Glyphosate residues below the European MRLs were most frequently found in dry lentils, linseeds, soya beans, dry peas, tea, buckwheat, barley, wheat and rye.[100] In Canada, a survey of 7,955 samples of food found that 42.3% contained detectable quantities of glyphosate and only 0.6% contained a level higher than the Canadian MRL of 0.1 mg/kg for most foods and 4 mg/kg for beans and chickpeas. Of the products that exceeded MRLs, one third were organic products. Health Canada concluded based on the analysis "that there was no long-term health risk to Canadian consumers from exposure to the levels of glyphosate".[101]

Toxicity

Glyphosate is the active ingredient in herbicide formulations containing it. However, in addition to glyphosate salts, commercial formulations of glyphosate contain additives (known as adjuvants) such as surfactants, which vary in nature and concentration. Surfactants such as polyethoxylated tallow amine (POEA) are added to glyphosate to enable it to wet the leaves and penetrate the cuticle of the plants.

Glyphosate alone

Humans

The acute oral toxicity for mammals is low,[102] but death has been reported after deliberate overdose of concentrated formulations.[103] The surfactants in glyphosate formulations can increase the relative acute toxicity of the formulation.[104][105] Glyphosate is less toxic than 94% of herbicides, and is also less toxic than household chemicals such as table salt or vinegar.[106]

In a 2017 risk assessment, the European Chemicals Agency (ECHA) wrote: "There is very limited information on skin irritation in humans. Where skin irritation has been reported, it is unclear whether it is related to glyphosate or co-formulants in glyphosate-containing herbicide formulations." The ECHA concluded that available human data was insufficient to support classification for skin corrosion or irritation.[107] Inhalation is a minor route of exposure, but spray mist may cause oral or nasal discomfort, an unpleasant taste in the mouth, or tingling and irritation in the throat. Eye exposure may lead to mild conjunctivitis. Superficial corneal injury is possible if irrigation is delayed or inadequate.[104]

Cancer

The consensus among national pesticide regulatory agencies and scientific organizations is that labeled uses of glyphosate have demonstrated no evidence of human carcinogenicity.[12] The Joint FAO/WHO Meeting on Pesticide Residues (JMPR),[108] the European Commission, the Canadian Pest Management Regulatory Agency, the Australian Pesticides and Veterinary Medicines Authority[109] and the German Federal Institute for Risk Assessment[110] have concluded that there is no evidence that glyphosate poses a carcinogenic or genotoxic risk to humans. The United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) has classified glyphosate as "not likely to be carcinogenic to humans."[111][112] One international scientific organization, the International Agency for Research on Cancer, classified glyphosate in Group 2A, "probably carcinogenic to humans" in 2015.[15][13]

As of 2020[update], the evidence for long-term exposure to glyphosate increasing the risk of human cancer remains inconclusive.[113] There is weak evidence human cancer risk might increase as a result of occupational exposure to large amounts of glyphosate, such as in agricultural work, but no good evidence of such a risk from home use, such as in domestic gardening.[114][115]

Although some small studies have suggested an association between glyphosate and non-hodgkin lymphoma, subsequent work confirmed the likelihood this work suffered from bias, and the association could not be demonstrated in more robust studies.[116][117][118]

Other mammals

Amongst mammals, glyphosate is considered to have "low to very low toxicity". The LD50 of glyphosate is 5,000 mg/kg for rats, 10,000 mg/kg in mice and 3,530 mg/kg in goats. The acute dermal LD50 in rabbits is greater than 2,000 mg/kg. Indications of glyphosate toxicity in animals typically appear within 30 to 120 minutes following ingestion of a large enough dose, and include initial excitability and tachycardia, ataxia, depression, and bradycardia, although severe toxicity can develop into collapse and convulsions.[56]

A review of unpublished short-term rabbit-feeding studies reported severe toxicity effects at 150 mg/kg/day and "no observed adverse effect level" doses ranging from 50 to 200 mg/kg/day.[119] Glyphosate can have carcinogenic effects in nonhuman mammals. These include the induction of positive trends in the incidence of renal tubule carcinoma and haemangiosarcoma in male mice, and increased pancreatic islet-cell adenoma in male rats.[13] In reproductive toxicity studies performed in rats and rabbits, no adverse maternal or offspring effects were seen at doses below 175–293 mg/kg/day.[56]

Large quantities of glyphosate-based herbicides may cause life-threatening arrhythmias in mammals. Evidence also shows that such herbicides cause direct electrophysiological changes in the cardiovascular systems of rats and rabbits.[120]

Aquatic fauna

In many freshwater invertebrates, glyphosate has a 48-hour LC50 ranging from 55 to 780 ppm. The 96-hour LC50 is 281 ppm for grass shrimp (Palaemonetas vulgaris) and 934 ppm for fiddler crabs (Uca pagilator). These values make glyphosate "slightly toxic to practically non-toxic".[56]

Antimicrobial activity

The antimicrobial activity of glyphosate has been described in the microbiology literature since its discovery in 1970 and the description of glyphosate's mechanism of action in 1972. Efficacy was described for numerous bacteria and fungi.[121] Glyphosate can control the growth of apicomplexan parasites, such as Toxoplasma gondii, Plasmodium falciparum (malaria), and Cryptosporidium parvum, and has been considered an antimicrobial agent in mammals.[122] Inhibition can occur with some Rhizobium species important for soybean nitrogen fixation, especially under moisture stress.[123]

Soil biota

When glyphosate comes into contact with the soil, it can be bound to soil particles, thereby slowing its degradation.[93][124] Glyphosate and its degradation product, aminomethylphosphonic acid are considered to be much more benign toxicologically and environmentally than most of the herbicides replaced by glyphosate.[125] A 2016 meta-analysis concluded that at typical application rates glyphosate had no effect on soil microbial biomass or respiration.[126] A 2016 review noted that contrasting effects of glyphosate on earthworms have been found in different experiments with some species unaffected, but others losing weight or avoiding treated soil. Further research is required to determine the impact of glyphosate on earthworms in complex ecosystems.[127]

Endocrine disruption

In 2007, the EPA selected glyphosate for further screening through its Endocrine Disruptor Screening Program (EDSP). Selection for this program is based on a compound's prevalence of use and does not imply particular suspicion of endocrine activity.[128] On June 29, 2015, the EPA released the Weight of Evidence Conclusions of the EDSP Tier 1 screening for glyphosate, recommending that glyphosate not be considered for Tier 2 testing. The Weight of Evidence conclusion stated "...there was no convincing evidence of potential interaction with the estrogen, androgen or thyroid pathways."[129] A review of the evidence by the European Food Safety Authority published in September 2017 showed conclusions similar to those of the EPA report.[130]

Effect on plant health

Some studies have found causal relationships between glyphosate and increased or decreased disease resistance.[131] Exposure to glyphosate has been shown to change the species composition of endophytic bacteria in plant hosts, which is highly variable.[132]

Glyphosate-based formulations

Glyphosate-based formulations may contain a number of adjuvants, the identities of which may be proprietary.[133] Surfactants are used in herbicide formulations as wetting agents, to maximize coverage and aid penetration of the herbicide(s) through plant leaves. As agricultural spray adjuvants, surfactants may be pre-mixed into commercial formulations or they may be purchased separately and mixed on-site.[134]

Polyethoxylated tallow amine (POEA) is a surfactant used in the original Roundup formulation and was commonly used in 2015.[135] Different versions of Roundup have included different percentages of POEA. A 1997 US government report said that Roundup is 15% POEA while Roundup Pro is 14.5%.[136] Since POEA is more toxic to fish and amphibians than glyphosate alone, POEA is not allowed in aquatic formulations.[137][136][138] A 2000 review of the ecotoxicological data on Roundup shows at least 58 studies exist on the effects of Roundup on a range of organisms.[94] This review concluded that "...for terrestrial uses of Roundup minimal acute and chronic risk was predicted for potentially exposed non-target organisms".[139]

Human

Overall, there is no conclusive evidence on glyphosate's effect on human health.[140][141]

Acute toxicity and chronic toxicity are dose-related. Skin exposure to ready-to-use concentrated glyphosate formulations can cause irritation, and photocontact dermatitis has been occasionally reported. These effects are probably due to the preservative benzisothiazolin-3-one. Severe skin burns are very rare.[104] Inhalation is a minor route of exposure, but spray mist may cause oral or nasal discomfort, an unpleasant taste in the mouth, or tingling and irritation in the throat. Eye exposure may lead to mild conjunctivitis. Superficial corneal injury is possible if irrigation is delayed or inadequate.[104] Death has been reported after deliberate overdose.[104][103] Ingestion of Roundup ranging from 85 to 200 ml (of 41% solution) has resulted in death within hours of ingestion, although it has also been ingested in quantities as large as 500 ml with only mild or moderate symptoms.[142] Adult consumption of more than 85 ml of concentrated product can lead to corrosive esophageal burns and kidney or liver damage. More severe cases cause "respiratory distress, impaired consciousness, pulmonary edema, infiltration on chest X-ray, shock, arrhythmias, renal failure requiring haemodialysis, metabolic acidosis, and hyperkalaemia" and death is often preceded by bradycardia and ventricular arrhythmias.[104] While the surfactants in formulations generally do not increase the toxicity of glyphosate itself, it is likely that they contribute to its acute toxicity.[104]

Aquatic fauna

Glyphosate products for aquatic use generally do not use surfactants, and aquatic formulations do not use POEA due to aquatic organism toxicity.[137] Due to the presence of POEA, such glyphosate formulations only allowed for terrestrial use are more toxic for amphibians and fish than glyphosate alone.[137][136][138] The half-life of POEA (21–42 days) is longer than that for glyphosate (7–14 days) in aquatic environments.[143] Aquatic organism exposure risk to terrestrial formulations with POEA is limited to drift or temporary water pockets where concentrations would be much lower than label rates.[137]

Some researchers have suggested the toxicity effects of pesticides on amphibians may be different from those of other aquatic fauna because of their lifestyle; amphibians may be more susceptible to the toxic effects of pesticides because they often prefer to breed in shallow, lentic, or ephemeral pools. These habitats do not necessarily constitute formal water-bodies and can contain higher concentrations of pesticide compared to larger water-bodies.[138][144] Studies in a variety of amphibians have shown the toxicity of GBFs containing POEA to amphibian larvae. These effects include interference with gill morphology and mortality from either the loss of osmotic stability or asphyxiation. At sub-lethal concentrations, exposure to POEA or glyphosate/POEA formulations have been associated with delayed development, accelerated development, reduced size at metamorphosis, developmental malformations of the tail, mouth, eye and head, histological indications of intersex and symptoms of oxidative stress.[138] Glyphosate-based formulations can cause oxidative stress in bullfrog tadpoles.[15]

A 2003 study of various formulations of glyphosate found, "[the] risk assessments based on estimated and measured concentrations of glyphosate that would result from its use for the control of undesirable plants in wetlands and over-water situations showed that the risk to aquatic organisms is negligible or small at application rates less than 4 kg/ha and only slightly greater at application rates of 8 kg/ha."[145]

A 2013 meta-analysis reviewed the available data related to potential impacts of glyphosate-based herbicides on amphibians. According to the authors, the use of glyphosate-based pesticides cannot be considered the major cause of amphibian decline, the bulk of which occurred prior to the widespread use of glyphosate or in pristine tropical areas with minimal glyphosate exposure. The authors recommended further study of per-species and per-development-stage chronic toxicity, of environmental glyphosate levels, and ongoing analysis of data relevant to determining what if any role glyphosate might be playing in worldwide amphibian decline, and suggest including amphibians in standardized test batteries.[146]

Genetic damage

Several studies have not found mutagenic effects,[147] so glyphosate has not been listed in the United States Environmental Protection Agency or the International Agency for Research on Cancer databases.[citation needed] Various other studies suggest glyphosate may be mutagenic.[citation needed] The IARC monograph noted that glyphosate-based formulations can cause DNA strand breaks in various taxa of animals in vitro.[15]

Government and organization positions

European Food Safety Authority

A 2013 systematic review by the German Institute for Risk Assessment (BfR) examined more than 1000[148] epidemiological studies, animal studies, and in vitro studies. It found that "no classification and labelling for carcinogenicity is warranted" and did not recommend a carcinogen classification of either 1A or 1B.[149]: 34–37, 139 It provided the review to EFSA in January 2014 which published it in December 2014.[149][150][151] In November 2015, EFSA published its conclusion in the Renewal Assessment Report (RAR), stating it was "unlikely to pose a carcinogenic hazard to humans".[152] The EU was largely informed by this report when it made its decision on the use of glyphosate in November 2017.[153]

EFSA's decision and the BfR report were criticized in an open letter published by 96 scientists in November 2015 saying that the BfR report failed to adhere to accepted scientific principles of open and transparent procedures.[154][155] The BfR report included unpublished data, lacked authorship, omitted references, and did not disclose conflict-of-interest information.[155]

In July 2023, EFSA re-evaluated after three years of assessment the putative impact of glyphosate on the health of humans, animals and the environment. As a result, no critical areas of concern were identified that would otherwise prevent glyphosate's registration renewal in the EU.[156][157][158]

International Agency for Research on Cancer

In March 2015, the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC), an intergovernmental agency forming part of the World Health Organization of the United Nations, published a summary of their forthcoming monograph on glyphosate, and classified glyphosate as "probably carcinogenic in humans" (category 2A) based on epidemiological studies, animal studies, and in vitro studies. It noted that there was "limited evidence" of carcinogenicity in humans for non-Hodgkin lymphoma.[10][13][14][15][159] The IARC classifies substances for their carcinogenic potential, and "a few positive findings can be enough to declare a hazard, even if there are negative studies, as well." Unlike the BfR, it does not conduct a risk assessment, weighing benefits against risk.[160]

The BfR responded that IARC reviewed only a selection of what they[who?] had reviewed earlier, and argued that other studies, including a cohort study called Agricultural Health Study, do not support the classification.[161] The IARC report did not include unpublished studies, including one completed by the IARC panel leader.[162] The agency's international protocol dictates that only published studies be used in classifications of carcinogenicity,[163] since national regulatory agencies including the EPA have allowed agrochemical corporations to conduct their own unpublished research, which may be biased in support of their profit motives.[164]

Reviews of the EFSA and IARC reports

A 2017 review done by personnel from EFSA and BfR argued that the differences between the IARC's and EFSA's conclusions regarding glyphosate and cancer were due to differences in their evaluation of the available evidence. The review concluded that "Two complementary exposure assessments ... suggests that actual exposure levels are below" the reference values identified by the EFSA "and do not represent a public concern."[12]

In contrast, a 2016 analysis by Christopher Portier, a scientist advising the IARC in the assessment of glyphosate and advocate for its classification as possibly carcinogenic, concluded that in the EFSA's Renewal Assessment Report, "almost no weight is given to studies from the published literature and there is an over-reliance on non-publicly available industry-provided studies using a limited set of assays that define the minimum data necessary for the marketing of a pesticide", arguing that the IARC's evaluation of probably carcinogenic to humans "accurately reflects the results of published scientific literature on glyphosate".[165]

In October 2017, an article in The Times revealed that Portier had received consulting contracts with two law firm associations representing alleged glyphosate cancer victims that included a payment of US$160,000 to Portier.[166][167] The IARC final report was also found to have changed compared to an interim report, through the removal of text saying certain studies had found glyphosate was not carcinogenic in that study's context, and through strengthening a conclusion of "limited evidence of animal carcinogenicity," to "sufficient evidence of animal carcinogenicity".[168]

US Environmental Protection Agency

In a 1993 review, the EPA, considered glyphosate to be noncarcinogenic and relatively low in dermal and oral acute toxicity.[93] The EPA considered a "worst case" dietary risk model of an individual eating a lifetime of food derived entirely from glyphosate-sprayed fields with residues at their maximum levels. This model indicated that no adverse health effects would be expected under such conditions.[93] In 2015, the EPA initiated a review of glyphosate's toxicity and in 2016 reported that glyphosate is likely not carcinogenic.[10][169] In August 2019, the EPA announced that it no longer allowed labels claiming glyphosate is a carcinogen, as those claims would "not meet the labeling requirements of the Federal Insecticide, Fungicide, and Rodenticide Act" and misinform the public.[170]

In 2017, evidence collected in a lawsuit brought against Monsanto by cancer patients revealed company emails which appeared to show a friendly relationship with a senior EPA official.[171]

Monsanto response and campaign

Monsanto called the IARC report biased and said it wanted the report to be retracted.[172] In 2017, internal documents from Monsanto were made public by lawyers pursuing litigation against the company,[173] who used the term "Monsanto papers" to describe the documents.[174] This term was later used also by Leemon McHenry[175] and others.[176] The documents indicated Monsanto had planned a public relations effort to discredit the IARC report, and had engaged Henry Miller to write a 2015 opinion piece in Forbes Magazine challenging the report. Miller did not reveal the connection to Forbes, and according to the New York Times, when Monsanto asked him if he was interested in writing such an article, he replied "I would be if I could start from a high-quality draft" provided by the company.[177] Once this became public, Forbes removed his blog from their site.

Two journalists from Le Monde won the 2018 European Press Prize for a series of articles on the documents, also titled Monsanto Papers. Their reporting described, among other things, Monsanto's lawyers' letters demanding that IARC scientists turn over documents relating to Monograph 112, which contained the IARC finding that glyphosate was a "probable carcinogen"; several of the scientists condemned these letters as intimidating.[178]

California Office of Environmental Health Hazard Assessment

In March 2015, the California Office of Environmental Health Hazard Assessment (OEHHA) announced plans to have glyphosate listed as a known carcinogen based on the IARC assessment. In 2016, Monsanto started a case against OEHHA and its acting director, Lauren Zeise,[179] but lost the suit in March 2017.[180]

Glyphosate was listed as "known to the State of California to cause cancer" in 2017, requiring warning labels under Proposition 65.[181] In February 2018, as part of an ongoing case, an injunction was issued prohibiting California from enforcing carcinogenicity labeling requirements for glyphosate until the case was resolved. The injunction stated that arguments by a US District Court Judge for the Eastern District of California "[do] not change the fact that the overwhelming majority of agencies that that have examined glyphosate have determined it is not a cancer risk."[182] In August 2019, the EPA also said it no longer allowed labels claiming glyphosate is a carcinogen, as those claims would "not meet the labeling requirements of the Federal Insecticide, Fungicide, and Rodenticide Act" and misinform the public.[170]

European Chemicals Agency

On March 15, 2017 the European Chemicals Agency (ECHA) announced recommendations proceeding from a risk assessment of glyphosate performed by ECHA's Committee for Risk Assessment (RAC). Their recommendations maintained the current classification of glyphosate as a substance causing serious eye damage and as a substance toxic to aquatic life. However, the RAC did not find evidence implicating glyphosate to be a carcinogen, a mutagen, toxic to reproduction, nor toxic to specific organs.[183] In 2022, the agency reiterated these findings in a later review and stated on cancer risk that, "Based on a wide-ranging review of scientific evidence, the committee again concludes that classifying glyphosate as a carcinogen is not justified."[184]

Effects of use

Emergence of resistant weeds

In the 1990s, no glyphosate-resistant weeds were known to exist.[185] In 2005 a slow upward trend began, resistant weeds appearing rarely around the world.[186] Another inflection point occurred in 2011 and resistance accelerated globally.[186] By 2014, glyphosate-resistant weeds dominated herbicide-resistance research. At that time, 23 glyphosate-resistant species were found in 18 countries.[187] "Resistance evolves after a weed population has been subjected to intense selection pressure in the form of repeated use of a single herbicide."[185][188]

According to Ian Heap, a weed specialist, who completed his PhD on resistance to multiple herbicides in annual ryegrass (Lolium rigidum) in 1988[189] – the first case of an herbicide-resistant weed in Australia[190] – by 2014 Lolium rigidum was the "world’s worst herbicide-resistant weed" with instances in "12 countries, 11 sites of action, 9 cropping regimens" and affecting "over 2 million hectares."[187] Annual ryegrass has been known to be resistant to herbicides since 1982. The first documented case of glyphosate-resistant L. rigidum was reported in Australia in 1996 near Orange, New South Wales.[191][192][193] In 2006, farmers associations were reporting 107 biotypes of weeds within 63 weed species with herbicide resistance.[194] In 2009, Canada identified its first resistant weed, giant ragweed, and at that time 15 weed species had been confirmed as resistant to glyphosate.[188][195] As of 2010, in the United States 7 to 10 million acres (2.8 to 4.0 million hectares) of soil were afflicted by herbicide-resistant weeds, or about 5% of the 170 million acres planted with corn, soybeans, and cotton, the crops most affected, in 22 states.[196] In 2012, Charles Benbrook reported that the Weed Science Society of America listed 22 herbicide-resistant species in the U.S., with over 5.7×106 ha (14×106 acres) infested by GR weeds and that Dow AgroSciences had carried out a survey and reported a figure of around 40×106 ha (100×106 acres).[197] The International Survey of Herbicide Resistant Weeds database lists species that are resistant to glyphosate.[195]

In response to resistant weeds, farmers are hand-weeding, using tractors to turn over soil between crops, and using other herbicides in addition to glyphosate.

Monsanto scientists have found that some resistant weeds have as many as 160 extra copies of a gene called EPSPS, the enzyme glyphosate disrupts.[198]

Palmer amaranth

In 2004, a glyphosate-resistant variation of Palmer amaranth was found in the U.S. state of Georgia.[199] In 2005, resistance was also found in North Carolina.[200] The species can quickly become resistant to multiple herbicides and has developed multiple mechanisms for glyphosate resistance due to selection pressure.[201][200] The glyphosate-resistant weed variant is now widespread in the southeastern United States.[199][202] Cases have also been reported in Texas[202] and Virginia.[203]

Conyza species

Conyza bonariensis (also known as hairy fleabane and buva) and C. canadensis (known as horseweed or marestail) are other weed species that have lately developed glyphosate resistance.[204][205][206] A 2008 study on the current situation of glyphosate resistance in South America concluded "resistance evolution followed intense glyphosate use" and the use of glyphosate-resistant soybean crops is a factor encouraging increases in glyphosate use.[207] In the 2015 growing season, glyphosate-resistant marestail proved to be especially problematic to control in Nebraska production fields.[208]

Ryegrass

Glyphosate-resistant ryegrass (Lolium) has occurred in most of the Australian agricultural areas and other areas of the world. All cases of evolution of resistance to glyphosate in Australia were characterized by intensive use of the herbicide while no other effective weed control practices were used. Studies indicate resistant ryegrass does not compete well against nonresistant plants and their numbers decrease when not grown under conditions of glyphosate application.[209]

Johnson grass

Glyphosate-resistant Johnson grass (Sorghum halepense) has been found in Argentina as well as Arkansas, Louisiana, and Mississippi.[210]

Monarch butterfly populations

Use of glyphosate and other herbicides like 2,4-D to clear milkweed along roads and fields may have contributed to a decline in monarch butterfly populations in the Midwestern United States.[211] Along with deforestation and adverse weather conditions,[212] the decrease in milkweed contributed to an 81% decline in monarchs.[213][214] The Natural Resources Defense Council (NRDC) filed a suit against the EPA in 2015, in which it argued that the agency ignored warnings about the potentially dangerous impacts of glyphosate usage on monarchs.[215]

Legal status

Glyphosate was first approved for use in the 1970s, and as of 2010 was labelled for use in 130 countries.[19]: 2

In 2017 Vandenberg et al. cited a 100-fold increase in the use of glyphosate-based herbicides from 1974 to 2014, the possibility that herbicide mixtures likely have effects that are not predicted by studying glyphosate alone, and reliance of current safety assessments on studies done over 30 years ago. They recommended that current safety standards be updated, writing that the current standards "may fail to protect public health or the environment."[216]

Europe

In April 2014, the legislature of the Netherlands passed legislation prohibiting sale of glyphosate to individuals for use at home; commercial sales were not affected.[217]

In June 2015, the French Ecology Minister asked nurseries and garden centers to halt over-the-counter sales of glyphosate in the form of Monsanto's Roundup. This was a nonbinding request and all sales of glyphosate remain legal in France until 2022, when it was planned to ban the substance for home gardening.[218] However, more recently the French parliament decided to not to impose a definitive date for such a ban.[219] In January 2019, "the sale, distribution, and use of Roundup 360 [wa]s banned" in France. Exemptions for many farmers were later implemented, and a curb of its use by 80% for 2021 is projected.[220][221]

A vote on the relicensing of glyphosate in the EU stalled in March 2016. Member states France, Sweden, and the Netherlands objected to the renewal.[222] A vote to reauthorize on a temporary basis failed in June 2016[223] but at the last minute the license was extended for 18 months until the end of 2017.[224]

On 27 November 2017, in the EU Council a majority of eighteen member states voted in favor of permitting the use of glyphosate for five more years. A qualified majority of sixteen states representing 65% of EU citizens was required to pass the law.[225] The German Minister of Agriculture, Christian Schmidt, unexpectedly voted in favor while the German coalition government was internally divided on the issue which usually results in Germany abstaining.[226]

In December 2018, attempts were made to reopen the decision to license the weed-killer. These were condemned by Conservative MEPs, who said the proposal was politically motivated and flew in the face of scientific evidence.[227]

In March 2019, the European Court of Justice (ECJ) ordered the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) to release all carcinogenicity and toxicity pesticide industry studies on glyphosate to the general public.[228]

In March 2019, the Austrian state of Carinthia outlawed the private use of glyphosate in residential areas while the commercial application of the herbicide is still permitted for farmers. The use of glyphosate by public authorities and road maintenance crews was already halted a number of years prior to the current ban by local authorities.[229]

In June 2019, Deutsche Bahn and Swiss Federal Railways announced that glyphosate and other commonly used herbicides for weed eradication along railway tracks will be phased out by 2025, while more environmentally sound methods for vegetation control are implemented.[230][231]

In July 2019, the Austrian parliament voted to ban glyphosate in Austria.[232]

In September 2019, the German Environment Ministry announced that the use of glyphosate will be banned from the end of 2023. The use of glyphosate-based herbicides will be reduced starting from 2020.[233]

The assessment process for an approval of glyphosate in the European Union will begin in December 2019. France, Hungary, the Netherlands and Sweden will jointly assess the application dossiers of the producers. The draft report of the assessment group will then be peer-reviewed by the EFSA before the current approval expires in December 2022.[234]

The date has since been pushed back, partially due to very high interest and input in the participation process, with the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) even calling it an “unprecedented number”.[235] Because the EFSA has to review all these 2400 comments and almost 400 responses, the process is expected to take longer. The created document is under extra review by the specially formed Glyphosate Renewal Group (GRG) and the Assessment Group on Glyphosate (AGG), the panel consisting of the four mentioned member states. With their responses now being scheduled for September 2022, the consultations with member states are supposed to be held by the very end of 2022.[236][237] This would allow to finish the final assessment by mid-2023 and pass it on to further legislature to decide.

In November 2023, glyphosate received 10 year renewed authorization for use in the EU.[238]

Other countries

In September 2013, the Legislative Assembly of El Salvador approved legislation to ban 53 agrochemicals, including glyphosate; the ban on glyphosate was set to begin in 2015.[239][240][241]

In the United States, the state of Minnesota preempts local laws that attempt to ban glyphosate. In 2015 there was an attempt to pass legislation at the state level that would repeal that preemption.[242]

In May 2015, the President of Sri Lanka banned the use and import of glyphosate, effective immediately.[243][244] However, in May 2018 the Sri Lankan government decided to re-authorize its use in the plantation sector.[245]

In May 2015, Bermuda blocked importation on all new orders of glyphosate-based herbicides for a temporary suspension awaiting outcomes of research.[246]

In May 2015, Colombia announced that it would stop using glyphosate by October 2015 in the destruction of illegal plantations of coca, the raw ingredient for cocaine. Farmers have complained that the aerial fumigation has destroyed entire fields of coffee and other legal produce.[71]

In April 2019, Vietnam's Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development banned the use of glyphosate throughout the country.[247]

In August 2020, Mexican President Andrés Manuel López Obrador announced that glyphosate will be gradually phased out of use in Mexico by late 2024.[248]

Thailand's National Hazardous Substances Committee decided to ban the use of glyphosate in October 2019[249] but reversed the decision in November 2019.[250]

After a court-ruling in 2018, glyphosate was temporarily banned in Brazil. This decision was later overturned, causing major criticism by the federal agency of health (Anvisa). This comes, as the latest evaluations declared glyphosate as noncarcinogenic. Since all carcinogenic agrichemicals are automatically banned in the country, this allowed the continuous use.[251]

In New Zealand, glyphosate is an approved herbicide for killing weeds,[252] with the most popular brand being Roundup.[252][253] Genetically modified crops designed to resist glyphosate are absent in New Zealand.[252] Crops applied with glyphosate must be regulated under the HSNO Act 1996 and ACVM Act 1997.[252][254] Legal status for glyphosate use in New Zealand is approved for commercial and personal use.[253] In 2021, exports of New Zealand honey were found to contain traces of glyphosate, causing some concern to Japanese importers.[255][256]

Legal cases

Lawsuits claiming liability for cancer

Since 2018, in a number of court cases in the United States, plaintiffs have argued that their cancer was caused by exposure to glyphosate in glyphosate-based herbicides produced by Monsanto/Bayer. Defendant Bayer has paid out over $9.6 billion in judgements and settlements in these cases. Bayer has also won at least 10 cases, successfully arguing that their glyphosate-based herbicides were not responsible for the plaintiff's cancer.[257]

Advertising controversies

In 2016, a lawsuit was filed against Quaker Oats in the Federal district courts of both New York and California after trace amounts of glyphosate were found in oatmeal. The lawsuit alleged that the claim of "100% natural" was false advertising.[258] That same year General Mills dropped the label "Made with 100% Natural Whole Grain Oats" from their Nature Valley granola bars after a lawsuit was filed that claimed the oats contained trace amounts of glyphosate.[259]

Trade dumping allegations

United States companies have cited trade issues with glyphosate being dumped into western world market areas by Chinese companies, and a formal dispute was filed in 2010.[260][261]

Misinformation campaigns

Glyphosate has become a locus of campaigning and misinformation by anti-GMO activists because of its association with genetically-modified glyphosate-resistant crops.[262]

The US politician Robert F. Kennedy Jr. has incorporated glyphosate into his anti-vaccination rhetoric, falsely claiming that both glyphosate and vaccines may be contributing to the American obesity epidemic.[262] Stephanie Seneff has also falsely claimed that it may have a role in autism and in worsening concussion.[263]

See also

References

- ^ Wilson, C. J. G.; Wood, P. A.; Parsons, S. (2022). "CSD Entry: PHOGLY05". Cambridge Structural Database: Access Structures. Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre. doi:10.5517/ccdc.csd.cc2dmhvd. Retrieved November 4, 2023.

- ^ Wilson, Cameron J. G.; Wood, Peter A.; Parsons, Simon (2023). "Discerning subtle high-pressure phase transitions in glyphosate". CrystEngComm. 25 (6): 988–997. doi:10.1039/D2CE01616H. hdl:20.500.11820/e81bbc4f-a6d1-4e16-a288-6eb9ff626485.

- ^ "glyphosate". Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary. Merriam-Webster. Retrieved June 28, 2020.

- ^ "glyphosate". Dictionary.com Unabridged (Online). n.d. Retrieved June 28, 2020.

- ^ "glyphosate". The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language (5th ed.). HarperCollins. Retrieved June 28, 2020.

- ^ a b Glyphosate, Environmental Health Criteria monograph No. 159, Geneva: World Health Organization, 1994, ISBN 92-4-157159-4

- ^ Index no. 607-315-00-8 of Annex VI, Part 3, to Regulation (EC) No 1272/2008 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 16 December 2008 on classification, labelling and packaging of substances and mixtures, amending and repealing Directives 67/548/EEC and 1999/45/EC, and amending Regulation (EC) No 1907/2006. Official Journal of the European Union L353, 31 December 2008, pp. 1–1355 at pp 570, 1100..

- ^ a b "2006-2007 Pesticide Market Estimates: Usage (Page 2) - Pesticides - US EPA". epa.gov. February 18, 2011. Archived from the original on June 26, 2015. Retrieved November 30, 2021.

- ^ Myers JP, Antoniou MN, Blumberg B, Carroll L, Colborn T, Everett LG, Hansen M, Landrigan PJ, Lanphear BP, Mesnage R, Vandenberg LN, vom Saal FS, Welshons WV, Benbroo CM (February 17, 2016). "Concerns over use of glyphosate-based herbicides and risks associated with exposures: a consensus statement". Environmental Health. 15 (19): 13. Bibcode:2016EnvHe..15...19M. doi:10.1186/s12940-016-0117-0. PMC 4756530. PMID 26883814.

- ^ a b c d Cressey D (March 25, 2015). "Widely used herbicide linked to cancer". Nature. doi:10.1038/nature.2015.17181. S2CID 131732731.

- ^ "Report of the Joint Committee on Pesticide Residues, WHO/FAO, Geneva, 16 May, 2016" (PDF).

- ^ a b c Tarazona, Jose V.; Court-Marques, Daniele; Tiramani, Manuela; Reich, Hermine; Pfeil, Rudolf; Istace, Frederique; Crivellente, Federica (April 3, 2017). "Glyphosate toxicity and carcinogenicity: a review of the scientific basis of the European Union assessment and its differences with IARC". Archives of Toxicology. 91 (8): 2723–43. Bibcode:2017ArTox..91.2723T. doi:10.1007/s00204-017-1962-5. PMC 5515989. PMID 28374158.

- ^ a b c d Guyton KZ, Loomis D, Grosse Y, El Ghissassi F, Benbrahim-Tallaa L, Guha N, Scoccianti C, Mattock H, Straif K (May 2015). "Carcinogenicity of tetrachlorvinphos, parathion, malathion, diazinon, and glyphosate". The Lancet Oncology. 16 (5): 490–91. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(15)70134-8. PMID 25801782.

- ^ a b "Press release: IARC Monographs Volume 112: evaluation of five organophosphate insecticides and herbicides" (PDF). International Agency for Research on Cancer, World Health Organization. March 20, 2015.

- ^ a b c d e "Glyphosate" (PDF). IARC Monographs on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans. 112. International Agency for Research on Cancer. August 11, 2016. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 30, 2019. Retrieved July 31, 2019.

- ^ "European Food Safety Authority – Glyphosate report" (PDF). EFSA. Retrieved May 23, 2016.

- ^ "Glyphosate: EFSA updates toxicological profile". European Food Safety Authority. November 12, 2015. Retrieved May 23, 2016.

- ^ "Glyphosate not classified as a carcinogen by ECHA". ECHA. March 15, 2017.

- ^ a b c d e f g Dill GM, Sammons RD, Feng PC, Kohn F, Kretzmer K, Mehrsheikh A, Bleeke M, Honegger JL, Farmer D, Wright D, Haupfear EA (2010). "Glyphosate: Discovery, Development, Applications, and Properties" (PDF). In Nandula VK (ed.). Glyphosate Resistance in Crops and Weeds: History, Development, and Management. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Inc. ISBN 978-0-470-41031-8.

- ^ a b Casida, John E. (January 6, 2017). "Organophosphorus Xenobiotic Toxicology". Annual Review of Pharmacology and Toxicology. 57 (1). Annual Reviews: 309–327. doi:10.1146/annurev-pharmtox-010716-104926. ISSN 0362-1642. PMID 28061690.

- ^ Swarthout, John T.; Bleeke, Marian S.; Vicini, John L. (June 16, 2018). "Comments for Mertens et al. (2018), Glyphosate, a chelating agent—relevant for ecological risk assessment?". Environmental Science and Pollution Research International. 25 (27): 27662–3. Bibcode:2018ESPR...2527662S. doi:10.1007/s11356-018-2506-0. PMC 6132386. PMID 29907899.

- ^ Alibhai MF, Stallings WC (March 2001). "Closing down on glyphosate inhibition – with a new structure for drug discovery". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 98 (6): 2944–46. Bibcode:2001PNAS...98.2944A. doi:10.1073/pnas.061025898. JSTOR 3055165. PMC 33334. PMID 11248008.

- ^ "Monsanto's John E. Franz Wins 1990 Perkin Medal". Chemical & Engineering News. 68 (11): 29–30. March 12, 1990. doi:10.1021/cen-v068n011.p029.

- ^ "The National Medal of Technology and Innovation Recipients – 1987". The United States Patent and Trademark Office. Retrieved November 29, 2012.

- ^ Stong C (May 1990). "People: Monsanto Scientist John E. Franz Wins 1990 Perkin Medal For Applied Chemistry". The Scientist. 4 (10): 28. Archived from the original on April 16, 2014.

- ^ "SCI Perkin Medal". Science History Institute. May 31, 2016. Retrieved March 24, 2018.

- ^ a b c Duke SO, Powles SB (2008), "Glyphosate: a once-in-a-century herbicide: Mini-review", Pest Management Science, 64 (4): 319–25, doi:10.1002/ps.1518, PMID 18273882, archived from the original (PDF) on July 2, 2019, retrieved April 13, 2014

- ^ "History of Monsanto's Glyphosate Herbicides" (PDF). Monsanto. Archived from the original (PDF) on August 7, 2018. Retrieved December 20, 2015.

- ^ US application 3799758, John E. Franz, "N-phosphonomethyl-glycine phytotoxicant compositions", published 1974-03-26, assigned to Monsanto Company

- ^ US application 4405531, John E. Franz, "Salts of N-phosphonomethylglycine", published 1983-09-20, assigned to Monsanto Company

- ^ Fernandez, Ivan (May 15, 2002). "The Glyphosate Market: A 'Roundup'". Frost & Sullivan. Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved March 10, 2015.

- ^ Powles SB (January 2010). "Gene amplification delivers glyphosate-resistant weed evolution". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 107 (3): 955–56. Bibcode:2010PNAS..107..955P. doi:10.1073/pnas.0913433107. PMC 2824278. PMID 20080659.

- ^ a b "Frequently Asked Questions on the Re-evaluation of Glyphosate". Pest Management Regulatory Agency of Canada. April 28, 2017. Retrieved May 10, 2018.

- ^ Chenier, Philip J. (2012). Survey of Industrial Chemistry (3rd ed.). Springer Science+Business Media. p. 384. ISBN 978-1461506034.

- ^ Schuette J. "Environmental Fate of Glyphosate" (PDF). Department of Pesticide Regulation, State of California. Archived from the original (PDF) on April 20, 2012. Retrieved June 4, 2012.

- ^ Zhou J, Li J, An R, Yuan H, Yu F (2012). "Study on a New Synthesis Approach of Glyphosate". J. Agric. Food Chem. 60 (25): 6279–85. doi:10.1021/jf301025p. PMID 22676441.

- ^ International Agency for Research on Cancer (2006). IARC Monographs on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans Volume 88: Formaldehyde, 2-Butoxyethanol and 1-tert-Butoxypropan-2-ol. Lyon: IARC/WHO. ISBN 978-9283212881.

- ^ National Toxicology Program (June 2011). Report on Carcinogens (12th ed.). Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, National Toxicology Program.

- ^ a b FAO (2014). FAO specifications and evaluations for agricultural pesticides: glyphosate (PDF). . Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. p. 5.

- ^ European Food Safety Authority (2015). "Conclusion on the peer review of the pesticide risk assessment of the active substance glyphosate". EFSA Journal. 13 (11:4302): 10. doi:10.2903/j.efsa.2015.4302.

- ^ Farm Chemicals International Glyphosate entry in Crop Protection Database

- ^ a b Alberta Agriculture and Rural Development. April 26, 2006. Quick Guide to Glyphosate Products – Frequently Asked Questions Archived July 26, 2017, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Hartzler, Bob. "Glyphosate: a Review". ISU Weed Science Online. Iowa State University Extension. Archived from the original on May 18, 2018. Retrieved August 26, 2012.

- ^ Tu M, Hurd C, Robison R, Randall JM (November 1, 2001). "Glyphosate" (PDF). Weed Control Methods Handbook. The Nature Conservancy.

- ^ National Pesticide Information Center. Last updated September 2010 Glyphosate General Fact Sheet

- ^ a b c d "Press Release: Research and Markets: Global Glyphosate Market for Genetically Modified and Conventional Crops 2013–2019". Reuters. April 30, 2014. Archived from the original on September 24, 2015.

- ^ monsanto.ca: "Vision Silviculture Herbicide" Archived April 7, 2016, at the Wayback Machine, 03-FEB-2011

- ^ China Research & Intelligence, June 5, 2013. Research Report on Global and China Glyphosate Industry, 2013–2017 Archived March 3, 2016, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Tu M, Randall JM (June 1, 2003). "Glyphosate" (PDF). Weed Control Methods Handbook. The Nature Conservancy.

- ^ Curran WS, McGlamery MD, Liebl RA, Lingenfelter DD (1999). "Adjuvants for Enhancing Herbicide Performance". Penn State Extension.

- ^ VanGessel M. "Glyphosate Formulations". Control Methods Handbook, Chapter 8, Adjuvants: Weekly Crop Update. University of Delaware Cooperative Extension. Archived from the original on June 13, 2010. Retrieved August 27, 2012.

- ^ "e-phy". e-phy.agriculture.gouv.fr.

- ^ Funke T, Han H, Healy-Fried ML, Fischer M, Schönbrunn E (August 2006). "Molecular basis for the herbicide resistance of Roundup Ready crops". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 103 (35): 13010–15. Bibcode:2006PNAS..10313010F. doi:10.1073/pnas.0603638103. JSTOR 30050705. PMC 1559744. PMID 16916934.

- ^ Maeda H, Dudareva N (2012). "The shikimate pathway and aromatic amino Acid biosynthesis in plants". Annual Review of Plant Biology. 63 (1): 73–105. doi:10.1146/annurev-arplant-042811-105439. PMID 22554242.

The AAA pathways consist of the shikimate pathway (the prechorismate pathway) and individual postchorismate pathways leading to Trp, Phe, and Tyr.... These pathways are found in bacteria, fungi, plants, and some protists, but are absent in animals. Therefore, AAAs and some of their derivatives (vitamins) are essential nutrients in the human diet, although in animals Tyr can be synthesized from Phe by Phe hydroxylase....The absence of the AAA pathways in animals also makes these pathways attractive targets for antimicrobial agents and herbicides.

- ^ Steinrücken HC, Amrhein N (June 1980). "The herbicide glyphosate is a potent inhibitor of 5-enolpyruvyl-shikimic acid-3-phosphate synthase". Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 94 (4): 1207–12. doi:10.1016/0006-291X(80)90547-1. PMID 7396959.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Glyphosate technical fact sheet (revised June 2015)". National Pesticide Information Center. 2010. Archived from the original on August 28, 2015. Retrieved September 1, 2015.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ a b c d "The agronomic benefits of glyphosate in Europe" (PDF). Monsanto Europe SA. February 2010. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 4, 2017. Retrieved June 2, 2013.

- ^ Hock B, Elstner EF (2004). Plant Toxicology, Fourth Edition. CRC Press. pp. 292–96. ISBN 978-0-203-02388-4.

- ^ Shick, J. Malcolm; Dunlap, Walter C. (2002). "Mycosporine-Like Amino Acids and Related Gadusols: Biosynthesis, Accumulation, and UV-Protective Functions in Aquatic Organisms". Annual Review of Physiology. 64 (1). Annual Reviews: 223–262. doi:10.1146/annurev.physiol.64.081501.155802. ISSN 0066-4278. PMID 11826269.

- ^ Kishore, Ganesh M.; Shah, Dilip M. (1988). "Amino Acid Biosynthesis Inhibitors as Herbicides". Annual Review of Biochemistry. 57 (1). Annual Reviews: 627–663. doi:10.1146/annurev.bi.57.070188.003211. ISSN 0066-4154. PMID 3052285.

- ^ Bentley, Ronald; Haslam, E. (1990). "The Shikimate Pathway — A Metabolic Tree with Many Branches". Critical Reviews in Biochemistry and Molecular Biology. 25 (5). Taylor & Francis: 307–384. doi:10.3109/10409239009090615. ISSN 1040-9238. PMID 2279393. S2CID 1667907.

- ^ Purdue University, Department of Horticulture and Landscape Architecture, Metabolic Plant Physiology Lecture notes, Aromatic amino acid biosynthesis, The shikimate pathway – synthesis of chorismate Archived December 19, 2007, at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Schönbrunn E, Eschenburg S, Shuttleworth WA, Schloss JV, Amrhein N, Evans JN, Kabsch W (February 2001). "Interaction of the herbicide glyphosate with its target enzyme 5-enolpyruvylshikimate 3-phosphate synthase in atomic detail". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 98 (4): 1376–80. Bibcode:2001PNAS...98.1376S. doi:10.1073/pnas.98.4.1376. PMC 29264. PMID 11171958.

- ^ Glyphosate bound to proteins in the Protein Data Bank

- ^ Schulz A, Krüper A, Amrhein N (1985). "Differential sensitivity of bacterial 5-enolpyruvylshikimate-3-phosphate synthases to the herbicide glyphosate". FEMS Microbiology Letters. 28 (3): 297–301. doi:10.1111/j.1574-6968.1985.tb00809.x.

- ^ a b Pollegioni L, Schonbrunn E, Siehl D (August 2011). "Molecular basis of glyphosate resistance-different approaches through protein engineering". The FEBS Journal. 278 (16): 2753–66. doi:10.1111/j.1742-4658.2011.08214.x. PMC 3145815. PMID 21668647.

- ^ Knezevic SZ (February 2010). "Use of Herbicide-Tolerant Crops as Part of an Integrated Weed Management Program". University of Nebraska Extension Integrated Weed Management Specialist. Archived from the original on June 15, 2010.

- ^ Nyamai PA, Prather TS, Wallace JM (2011). "Evaluating Restoration Methods across a Range of Plant Communities Dominated by Invasive Annual Grasses to Native Perennial Grasses". Invasive Plant Science and Management. 4 (3): 306–16. doi:10.1614/IPSM-D-09-00048.1. S2CID 84696972.

- ^ Luijendijk CD, Beltman WH, Smidt RA, van der Pas LJ, Kempenaar C (May 2005). "Measures to reduce glyphosate runoff from hard surfaces" (PDF). Plant Research International B.V. Wageningen.

- ^ Botta F, Lavison G, Couturier G, Alliot F, Moreau-Guigon E, Fauchon N, Guery B, Chevreuil M, Blanchoud H (September 2009). "Transfer of glyphosate and its degradate AMPA to surface waters through urban sewerage systems". Chemosphere. 77 (1): 133–39. Bibcode:2009Chmsp..77..133B. doi:10.1016/j.chemosphere.2009.05.008. PMID 19482331.

- ^ a b BBC. May 10, 2015. Colombia to ban coca spraying herbicide glyphosate

- ^ MacLean, Amy-Jean. "Desiccant vs. Glyphosate: know your goals". PortageOnline.com. Golden West. Archived from the original on July 31, 2019. Retrieved August 19, 2016.

- ^ "Crop Desiccation". Sustainable Agricultural Innovations & Food. University of Saskatchewan. October 25, 2016. Archived from the original on July 31, 2019. Retrieved July 31, 2019.

- ^ In agriculture, the term desiccant is applied to an agent that promotes dry down. "True desiccants" are not chemical desiccants either, rather the distinction is whether an agent is a contact herbicide such as Diquat and sodium chlorate that rapidly kill the above-ground portion of the plant as it dries out over a few days,[73] or an agent such as glyphosate that is absorbed systemically and translocated to the root, a process that can take days to weeks.

- ^ Sprague, Christy (August 20, 2015). "Preharvest herbicide applications are an important part of direct-harvest dry bean production". Michigan State University. Michigan State University Extension, Department of Plant, Soil and Microbial Sciences. Retrieved August 20, 2015.

- ^ Gravois, Kenneth (August 14, 2017). "Sugarcane Ripener Recommendations". LSU AgCenter. Louisiana State University, College of Agriculture. Archived from the original on September 20, 2018.

- ^ "Pre-harvest Management of Small Grains". Minnesota Crop News. University of Minnesota Extension. July 18, 2017. Archived from the original on May 27, 2019.

- ^ Fowler, D.B. "Harvesting, Grain Drying and Storage – Chapter 23". Winter Wheat Production Manual. University of Saskatchewan. Archived from the original on December 9, 2018. Retrieved May 3, 2017.

- ^ Green JM, Owen MD (June 2011). "Herbicide-resistant crops: utilities and limitations for herbicide-resistant weed management". Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 59 (11): 5819–29. doi:10.1021/jf101286h. PMC 3105486. PMID 20586458.

- ^ Rashid A (2009). Introduction to Genetic Engineering of Crop Plants: Aims and Achievements. I K International. p. 259. ISBN 978-93-80026-16-9.

- ^ "Company History". Web Site. Monsanto Company. Archived from the original on November 5, 2018. Retrieved June 27, 2017.

- ^ "Adoption of Genetically Engineered Crops in the U.S." Economic Research Service. USDA. Retrieved March 26, 2024.

- ^ P. Sprankle, W. F. Meggitt, D. Penner: Adsorption, mobility, and microbial degradation of glyphosate in the soil. In: Weed Sci. 23(3), p. 229–234, as cited in Environmental Health Criteria 159.

- ^ "PubChem Compound Summary for CID 3496, Glyphosate". National Center for Biotechnology Information. Retrieved June 16, 2022.

- ^ a b Borggaard OK, Gimsing AL (April 2008). "Fate of glyphosate in soil and the possibility of leaching to ground and surface waters: a review". Pest Management Science. 64 (4): 441–56. doi:10.1002/ps.1512. PMID 18161065.

- ^ Botta F, Lavisonb G, Couturier G, Alliot F, Moreau-Guigon E, Fauchon N, Guery B, Chevreuil M, Blanchoud H (2009). "Transfer of glyphosate and its degradate AMPA to surface waters through urban sewerage systems". Chemosphere. 77 (1): 133–139. Bibcode:2009Chmsp..77..133B. doi:10.1016/j.chemosphere.2009.05.008. PMID 19482331.

- ^ Schwientek, M.; Rügner, H.; Haderlein, S.B.; Schulz, W.; Wimmer, B.; Engelbart, L.; Bieger, S.; Huhn, C. (2024). "Glyphosate contamination in European rivers not from herbicide application?". Water Research. 263: 122140. doi:10.1016/j.watres.2024.122140.

- ^ Battaglin, W.A.; Meyer, M.T.; Kuivila, K.M.; Dietze, J.E. (April 2014). "Glyphosate and Its Degradation Product AMPA Occur Frequently and Widely in U.S. Soils, Surface Water, Groundwater, and Precipitation". JAWRA Journal of the American Water Resources Association. 50 (2): 275–90. Bibcode:2014JAWRA..50..275B. doi:10.1111/jawr.12159. S2CID 15865832.

- ^ Mahler, Barbara J.; Van Metre, Peter C.; Burley, Thomas E.; Loftin, Keith A.; Meyer, Michael T.; Nowell, Lisa H. (February 2017). "Similarities and differences in occurrence and temporal fluctuations in glyphosate and atrazine in small Midwestern streams (USA) during the 2013 growing season". Science of the Total Environment. 579: 149–58. Bibcode:2017ScTEn.579..149M. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2016.10.236. PMID 27863869.

- ^ Richards, Brian K.; Pacenka, Steven; Meyer, Michael T.; Dietze, Julie E.; Schatz, Anna L.; Teuffer, Karin; Aristilde, Ludmilla; Steenhuis, Tammo S. (April 23, 2018). "Antecedent and Post-Application Rain Events Trigger Glyphosate Transport from Runoff-Prone Soils". Environmental Science & Technology Letters. 5 (5): 249–54. Bibcode:2018EnSTL...5..249R. doi:10.1021/acs.estlett.8b00085.