Katabatic wind

This article needs additional citations for verification. (August 2024) |

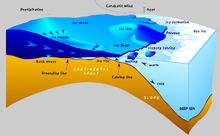

A katabatic wind (named from Ancient Greek κατάβασις (katábasis) 'descent') carries high-density air from a higher elevation down a slope under the force of gravity. Such winds are sometimes also called fall winds; the spelling catabatic[1] is also used. Katabatic winds can rush down elevated slopes at hurricane speeds, but most are not that intense and many are 10 knots (19 km/h; 12 mph) or less.

Not all downslope winds are katabatic. For instance, winds such as the föhn and chinook are rain shadow winds where air driven upslope on the windward side of a mountain range drops its moisture and descends leeward drier and warmer. Examples of true katabatic winds include the bora in the Adriatic, the Bohemian Wind or Böhmwind in the Ore Mountains, the Santa Ana in southern California, the piteraq winds of Greenland, and the oroshi in Japan. Another example is "the Barber", an enhanced katabatic wind that blows over the town of Greymouth in New Zealand when there is a southeast flow over the South Island. "The Barber" has a local reputation for its coldness.

Mechanism

[edit]

A katabatic wind originates from radiational cooling of air atop a plateau, a mountain, glacier, or even a hill. Since the density of air is inversely proportional to temperature, the air will flow downwards, warming approximately adiabatically as it descends. The temperature of the air depends on the temperature in the source region and the amount of descent. In the case of the Santa Ana, for example, the wind can (but does not always) become hot by the time it reaches sea level. In Antarctica, by contrast, the wind is still intensely cold.[citation needed]

The entire near-surface wind field over Antarctica is largely determined by the katabatic winds, particularly outside the summer season, except in coastal regions when storms may impose their own wind field.[citation needed]

Impacts

[edit]

Katabatic winds are most commonly found blowing out from the large and elevated ice sheets of Antarctica and Greenland. The buildup of high density cold air over the ice sheets and the elevation of the ice sheets brings into play enormous gravitational energy. Where these winds are concentrated into restricted areas in the coastal valleys, the winds blow well over hurricane force,[2] reaching around 160 kn (300 km/h; 180 mph).[3] In Greenland these winds are called piteraq and are most intense whenever a low pressure area approaches the coast.

In a few regions of continental Antarctica the snow is scoured away by the force of the katabatic winds, leading to "dry valleys" (or "Antarctic oases") such as the McMurdo Dry Valleys. Since the katabatic winds are descending, they tend to have a low relative humidity, which desiccates the region. Other regions may have a similar but lesser effect, leading to "blue ice" areas where the snow is removed and the surface ice sublimates, but is replenished by glacier flow from upstream.

In the Fuegian Archipelago (Tierra del Fuego) in South America as well as in Alaska in North America, a wind known as a williwaw is a particular danger to harboring vessels. Williwaws originate in the snow and ice fields of the coastal mountains, and they can be faster than 120 kn (220 km/h; 140 mph).[4]

In California, strong katabatic wind events have been responsible for the explosive growth of many wildfires, including the 2018 Camp Fire and the 2020 North Complex.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^

The NASA Scope and Subject Category Guide. NASA SP. Vol. 7603. National Aeronautics and Space Administration, Scientific and Technical Information Office, Center for Aerospace Information. 2000. p. 71. Retrieved 2018-01-17.

Katabatic winds (also catabatic)

- ^ Climate: The South Pole Archived 2008-09-18 at the Wayback Machine Stanford Humanities Lab Archived 2006-09-12 at archive.today, Retrieved 2008-10-01

- ^ Trewby, M. (Ed., 2002): Antarctica. An encyclopedia from Abbott Ice Shelf to Zooplankton Firefly Books Ltd. ISBN 1-55297-590-8

- ^ Williwaw weatheronline.co.uk. Accessed 2013-04-29.

Further reading

[edit]- Bromwich, David H. (1989). "Satellite Analyses of Antarctic Katabatic Wind Behavior". Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society. 70 (7): 738–49. Bibcode:1989BAMS...70..738B. doi:10.1175/1520-0477(1989)070<0738:SAOAKW>2.0.CO;2.

- Bromwich, David H. (1989). "An Extraordinary Katabatic Wind Regime at Terra Nova Bay, Antarctica". Monthly Weather Review. 117 (3): 688–95. Bibcode:1989MWRv..117..688B. doi:10.1175/1520-0493(1989)117<0688:AEKWRA>2.0.CO;2.

- Giles, Bill. Weather A-Z - Katabatic Winds By Bill Giles OBE, BBC, Retrieved 2008-10-14

- McKnight, TL & Hess, Darrel (2000). Katabatic Winds. In Physical Geography: A Landscape Appreciation, pp. 131–2. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall. ISBN 0-13-020263-0

- Parish, Thomas R.; Bromwich, David H. (1991). "Continental-Scale Simulation of the Antarctic Katabatic Wind Regime". Journal of Climate. 4 (2): 135–46. Bibcode:1991JCli....4..135P. doi:10.1175/1520-0442(1991)004<0135:CSSOTA>2.0.CO;2.

External links

[edit] Media related to Katabatic wind at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Katabatic wind at Wikimedia Commons