Korean language and computers

This article may be too technical for most readers to understand. (July 2022) |

The writing system of the Korean language is a syllabic alphabet of character parts (jamo) organized into character blocks (geulja) representing syllables. The character parts cannot be written from left to right on the computer, as in many Western languages. Every possible syllable in Korean would have to be rendered as syllable blocks by a font, or each character part would have to be encoded separately. Unicode has both options; the character parts ㅎ (h) and ㅏ (a), and the combined syllable 하 (ha), are encoded.

Character encoding

[edit]In RFC 1557, a method known as ISO-2022-KR for seven-bit encoding of Korean characters in email was described. Where eight bits are allowed, EUC-KR encoding is preferred. These two encodings combine US-ASCII (ISO 646) with the Korean standard KS X 1001:1992[1] (previously named KS C 5601:1987). Another character set, KPS 9566 (similar to KS X 1001), is used in North Korea.

The international Unicode standard contains special characters for the Korean language in the Hangul phonetic system. Unicode supports two methods. The method used by Microsoft Windows is to have each of the 11,172 syllable combinations as code and a preformed font character. The other method encodes letters (jamos) and lets the software combine them correctly. The Windows method requires more font memory but allows better shapes, since it is complicated to create stylistically correct combinations (preferable for documents).

Another possibility is stacking a sequence of medial(s) (jungseong) and a sequence of final(s) (jongseong) or a Middle Korean pitch mark (if needed) on top of the sequence of initial(s) (choseong) if the font has medial and final jamos with zero-width spacing inserted to the left of the cursor or caret, thus appearing in the right place below (or to the right of) the initial. If a syllable has a horizontal medial (ㅗ, ㅛ, ㅜ, ㅠ or ㅡ), the initial will probably appear further left in a complete syllable than in preformed syllables due to the space that must be reserved for a vertical medial, making aesthetically poor what may be the only way to display Middle Korean hangul text without resorting to images, romanization, replacement of obsolete jamo or non-standard encodings. However, most current fonts do not support this.

The Unicode standard also has attempted to create a unified CJK character set which can represent Chinese (Hanzi) and the Japanese (Kanji) and Korean (Hanja) derivatives of this script through Han unification, which does not discriminate by language or region in rendering Chinese characters if the typographic traditions have not resulted in major differences in what a character looks like. Han unification has been criticized.

Hangul type, Korean typewriters

[edit]While the first Korean typewriter, or 한글 타자기, is unclear,the first Moa-Sugi style (모아쓰기,The form of hangul where consonants and vowels come together to form a letter; The standard form of Hangul used today) typewriter is thought to be first invented by Korean-American gyopo Lee Won-Ik (이원익) in 1914, where he modified a Smith Premier 10 typewriter's type into Hangul.[2][3] Alongside Lee Won-ik's, Horace Grant Underwood's 1913 US-patented Hangul type, the Underwood, and another Korean-American Kim Jun-Sung's Hangul type are also brought up when discussing the first Moa-Sugi type.[4]

In 1929, the first Dubeolsik typewriter was made by Song Ki-Ju, a student studying abroad in the US, gaining attention from the Donga ilbo, however, it no longer exists; In 1934 he showcased another type, which was a modification of the Underwood portable.[5][6] Song's 1934 typewriter is stored in the Hangul museum as the oldest existing Korean typewriter.[7] The invention led to the development of other typewriters in 1945 by Kim Joon Sung and 1950 by Kong Byung Woo.[8]

In 1949, eye doctor Kong Byung-Woo made the first practical Hangul type able to write both in Moa-Sugi and horizontally.[9]

Modern text input

[edit]

On a Korean computer keyboard, text is typically entered by pressing a key for the appropriate jamo; the operating system creates each composite character on the fly. Depending on the Input method editor and keyboard layout, double consonants can be entered by holding the shift button. When all jamo making up a syllabic block has been entered, the user may initiate a conversion to hanja (or other special characters) using a keyboard shortcut or interface button; South Korean keyboards have a key for this. Subsequent semi-automated hanja conversion is supported in varying degrees by word processors.

When using a keyboard with another language, most operating systems require the user to type with an original Korean keyboard layout; the most common is Dubeolsik. In other languages, such as Japanese, text can be entered on non-native keyboards with romanization.

Operating systems such as Linux allow engine/hangul/hangul-keyboard='ro, resulting in a romaja keyboard; typing "seonggye" results in 성계.[10] In this configuration, ㄲ is obtained by "gg" rather than ⇧ Shift+G. This allows keying "jasanGun" to obtain 자산군, instead of keying "jasangun" (which would provide 자상운).

Before Korean division

[edit]Korean text input is related to Korean typewriters (타자기) before computers. according to Jang Bong Seon, Horace Grant Underwood made a Korean typewriter during the first decade of the 20th century.[11] In 1927, Song Ki Joo invented the first Dubeolsik typewriter in Chicago; h

After division

[edit]South Korea originally had a Nebeolsik standard, but Dubeolsik became standard in 1985.[12]

Hanja

[edit]Some Korean fonts do not include hanja, and word processors do not allow a user to specify which font to use as a fallback for any hanja in a text; each hanja sequence must be manually formatted for a desired font.

Pitch marks and vertical text

[edit]Vertical text is supported poorly (or not at all) by HTML and most word processors. This is not an issue for modern Korean, which is usually written horizontally; until the second half of the 20th century, however, Korean was often written vertically. Fifteenth-century texts written in hangul had pitch marks to the left of syllables which are included in Unicode, although current fonts do not support them.

Programs

[edit]Programs designed for Korean language-related use include:

- Language recognition

- A North Korean speech recognition program is said to recognize 100,000 words, with a success rate of over 90 percent.[13]

- Mongnan (목란; Korea Computer Center,[14] North Korea) – Optical character recognition software, with a reported success rate of 99 percent for printed text and 95 percent for handwriting recognition.[13]

- Input method editors

- Tan'gun (단군; Pyongyang Information Center, North Korea) – Allows hangul on English versions of Windows.[14]

- Nalgaeset Hangul Input Method Editor (날개셋 한글 입력기); Kim Yongmook, South Korea) – A hangul input method developed for the 3(se)-beolsik Windows keyboard layout

- Nabi (나비), ami (아미; South Korea) – Permits hangul on Linux

- m17n – Permits revised romanization for hangul input on Unix

- SCIM and IBus – Permits hangul and hanja input on POSIX operating systems (including Linux and BSD)

- Word processors – The following programs include domestic hangul fonts, non-hangul fonts and a hangul-hanja conversion utility.

- Hangul (Hancom, South Korea)

- Changdok (창덕; PIC,[14] North Korea) – MS-DOS program developed in April 1990; a Windows version was developed in 1996.[15] It has a personality-cult feature in which pressing Ctrl+I or Ctrl+J produces titles praising Kim Il Sung and Kim Jong Il, respectively.[16]

Hangul in Unicode

[edit]

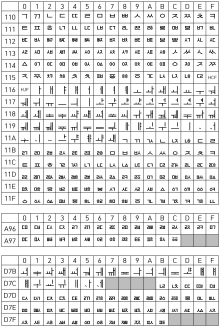

Hangul letters are detailed in several parts of Unicode:

- Hangul Syllables (AC00–D7A3)

- Hangul Jamo (1100–11FF)

- Hangul Compatibility Jamo (3130–318F)

- Hangul Jamo Extended-A (A960–A97F)

- Hangul Jamo Extended-B (D7B0–D7FF)

Hangul syllables block

[edit]Pre-composed hangul syllables in the Unicode hangul syllables block are algorithmically defined with the following formula:

- [(initial) × 588 + (medial) × 28 + (final)] + 44032

- Initial consonants

- Medial vowels

- Final consonants

To find the code point of "한" in Unicode:

- The value of the initial consonant (ㅎ) is 18.

- The value of the medial vowel (ㅏ) is 0.

- The value of the final consonant (ㄴ) is 4.

Substituting these values in the formula above yields [(18 × 588) + (0 × 28) + 4] + 44032 = 54620. The Unicode value of 한 is 54620 in decimal, 한 in numeric character reference, and U+D55C in hexadecimal Unicode notation.

How to code this in Rust

[edit]With the below module, calling e.g. hangul::from_jamo('ㅎ', 'ㅏ', Some('ㄴ')) will return Some('한').

mod hangul {

const INITIAL_JAMO: [char; 19] = [

'ㄱ', 'ㄲ', 'ㄴ', 'ㄷ',

'ㄸ', 'ㄹ', 'ㅁ', 'ㅂ',

'ㅃ', 'ㅅ', 'ㅆ', 'ㅇ',

'ㅈ', 'ㅉ', 'ㅊ', 'ㅋ',

'ㅌ', 'ㅍ', 'ㅎ',

];

const VOWEL_JAMO: [char; 21] = [

'ㅏ', 'ㅐ', 'ㅑ', 'ㅒ',

'ㅓ', 'ㅔ', 'ㅕ', 'ㅖ',

'ㅗ', 'ㅘ', 'ㅙ', 'ㅚ',

'ㅛ', 'ㅜ', 'ㅝ', 'ㅞ',

'ㅟ', 'ㅠ', 'ㅡ', 'ㅢ',

'ㅣ',

];

const FINAL_JAMO: [Option<char>; 28] = [

None, Some('ㄱ'), Some('ㄲ'), Some('ㄳ'),

Some('ㄴ'), Some('ㄵ'), Some('ㄶ'), Some('ㄷ'),

Some('ㄹ'), Some('ㄺ'), Some('ㄻ'), Some('ㄼ'),

Some('ㄽ'), Some('ㄾ'), Some('ㄿ'), Some('ㅀ'),

Some('ㅁ'), Some('ㅂ'), Some('ㅄ'), Some('ㅅ'),

Some('ㅆ'), Some('ㅇ'), Some('ㅈ'), Some('ㅊ'),

Some('ㅋ'), Some('ㅌ'), Some('ㅍ'), Some('ㅎ'),

];

const GA_LOCATION: u32 = '가' as u32; // = 44_032

pub fn from_jamo(initial: char, medial: char, last: Option<char>) -> Option<char> {

if !(

self::INITIAL_JAMO.contains(&initial)

&& self::VOWEL_JAMO.contains(&medial)

&& self::FINAL_JAMO.contains(&last)

) {

return None;

}

char::from_u32(

self::GA_LOCATION

+ 588 * (INITIAL_JAMO.iter().position(|&c| c == initial)? as u32)

+ 28 * (VOWEL_JAMO.iter().position(|&c| c == medial)? as u32)

+ FINAL_JAMO.iter().position(|&c| c == last)? as u32

)

}

}

Hangul Compatibility Jamo block

[edit]The Unicode Hangul Compatibility Jamo block has been allocated for compatibility with the KS X 1001 character set. It is usually used to represent hangul without distinguishing initials and finals.

Hangul Jamo blocks

[edit]The Hangul Jamo, Hangul Jamo Extended-A and Hangul Jamo Extended-B blocks contain initial, medial and final jamo, including obsolete jamo.

Hanyang Private Use Area code

[edit]Hangul (word processor) shipped with fonts from Hanyang Information and Communication, which map obsolete hangul characters with Unicode's Private Use Areas. Despite the use of PUAs instead of dedicated code points, Hanyang's mapping was the most popular way to represent obsolete hangul in South Korea in 2007. With its Hangul 2010, however, Hancom deprecated Hanyang PUA code and began representing obsolete hangul characters with Unicode hangul jamo.

See also

[edit]- Japanese language and computers

- Vietnamese language and computers

- List of CJK fonts

- Chinese input methods for computers

- McCune–Reischauer

- Yale romanization of Korean

- Revised Romanization of Korean

- New Korean Orthography

References

[edit]- ^ "KS X 1001:1992" (PDF).

- ^ "이원익 타자기". scienceall.com. December 7, 2012.

- ^ "정보화 시대 이전, 타자기가 있었다<한글 타자기 전성시대>". Hangul museum.

- ^ 김태호 (2011), 15쪽.

- ^ https://www.hangeul.go.kr/museumCollection/museumCollectionView.do?curr_menu_cd=0106010100&collection_id=%ED%95%9C%EA%B8%B01&lang=ko&seq=30

- ^ 김태호 (2011), 25쪽.

- ^ "[역사특집] 한국교회사에서 건진 근대문화유산들, 등록문화재로 새롭게 지정". Christian newspaper. February 27, 2020.

- ^ "最古 한글타자기, 한글박물관서 본다". Yonhap News Agency. October 8, 2014.

- ^ 김태호 (2011), 28쪽.

- ^ "Libhangul/Ibus-hangul". GitHub. May 29, 2021.

- ^ 장, 봉선 (1989). 한글풀어쓰기교본. 한풀문화사(Hanpul). p. 84.

- ^ "한글 타자 자판표준화 등 한글 기계화(1969년)". theme.archives.go.kr.

- ^ a b 김, 치관 (December 2, 2000). 문답으로 보는 북한 정보화의 현주소. Tongilnews.com (in Korean). Retrieved December 3, 2006.

- ^ a b c 김, 효석 (December 2, 2000). "<국회자료집> 북한 S/W 현황과 시연자료". Tongilnews.com (in Korean). Retrieved December 3, 2006.

- ^ Yonhap (January 7, 1998). 북한의 컴퓨터산업 어디까지 왔나. Tongilnews.com (in Korean). Retrieved December 3, 2006. [dead link]

- ^ "북한용어사전: 평양정보센터(PIC)" (in Korean). Archived from the original on September 28, 2007. Retrieved December 3, 2006.

External links

[edit]- Online Korean Virtual Keyboard

- InputKing Online Input System, an online tool for typing Korean

- "Jamo in Unicode" (PDF). (186 KB)

- "Hangul syllables" (PDF). (3.86 MB)

- Hoffmann, Frank. "Korean Studies: Unicode Converter". koreanstudies.com., an online tool for converting Korean text into various coding formats and vice versa