Kwaidan (film)

| Kwaidan | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

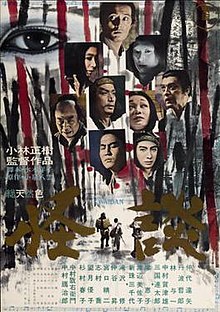

Theatrical release poster | |||||

| Japanese name | |||||

| Kanji | 怪談 | ||||

| |||||

| Directed by | Masaki Kobayashi | ||||

| Screenplay by | Yoko Mizuki[1] | ||||

| Based on | Stories and Studies of Strange Things by Lafcadio Hearn | ||||

| Produced by | Shigeru Wakatsuki[1] | ||||

| Starring | |||||

| Cinematography | Yoshio Miyajima[1] | ||||

| Edited by | Hisashi Sagara[1] | ||||

| Music by | Toru Takemitsu[1] | ||||

Production company | Ninjin Club[1] | ||||

| Distributed by | Toho | ||||

Release date |

| ||||

Running time | 182 minutes[1] | ||||

| Country | Japan | ||||

| Language | Japanese | ||||

| Budget | ¥320 million[2][3] | ||||

| Box office | ¥225 million[4] | ||||

Kwaidan (Japanese: 怪談, Hepburn: Kaidan, lit. 'Ghost Stories') is a 1964 Japanese anthology horror film directed by Masaki Kobayashi. It is based on stories from Lafcadio Hearn's collections of Japanese folk tales, mainly Kwaidan: Stories and Studies of Strange Things (1904), for which it is named. The film consists of four separate and unrelated stories. Kwaidan is an archaic transliteration of the term kaidan, meaning "ghost story". Receiving critical acclaim, the film won the Special Jury Prize at the 1965 Cannes Film Festival,[5] and received an Academy Award nomination for Best Foreign Language Film.[6]

Plot

[edit]"The Black Hair"

[edit]"The Black Hair" (黒髪, Kurokami) is adapted from "The Reconciliation" and "The Corpse Rider", which appeared in Hearn's collection Shadowings (1900).

An impoverished swordsman in Kyoto divorces his wife, a weaver, and leaves her for a woman of a wealthy family to attain greater social status. However, despite his new wealthy status, the swordsman's second marriage proves to be unhappy. His new wife is shown to be callous and selfish. The swordsman regrets leaving his more devoted and patient ex-wife.

The second wife is furious when she realizes that the swordsman not only married her to obtain her family's wealth, but also still longs for his old life in Kyoto with his ex-wife. When he is told to go into the chambers to reconcile with her, the swordsman refuses, stating his intent to return home and reconcile with his ex-wife. He points out his foolish behavior and poverty as the reasons why he reacted the way he did. The swordsman informs his lady-in-waiting to tell his second wife that their marriage is over and she can return to her parents in shame.

After a few years, the swordsman returns to find his home, and his wife, largely unchanged. He reconciles with his ex-wife, who refuses to let him punish himself. She mentions that Kyoto has "changed" and that they only have "a moment" together, but does not elaborate further. She assures him that she understood that he only left her in order to bring income to their home. The two happily exchange wonderful stories about the past and the future until the swordsman falls asleep. He wakes up the following day only to discover that he had been sleeping next to his ex-wife's rotted corpse. Rapidly aging, he stumbles through the house, finding that it actually is in ruins and overgrown with weeds. He manages to escape, only to be attacked by his ex-wife's black hair.

"The Woman of the Snow"

[edit]"The Woman of the Snow" (雪女, Yukionna) is an adaptation from Hearn's Kwaidan: Stories and Studies of Strange Things (1903).

Two woodcutters named Minokichi and Mosaku take refuge in a boatman's hut during a snowstorm. Mosaku is killed by a yuki-onna. When the yuki-onna turns to Minokichi, she sympathetically remarks that he is a handsome boy and spares him because of his youth, warning him to never mention what happened or she will kill him. Minokichi returns home and never mentions that night.

One day while cutting wood, Minokichi meets Yuki, a beautiful young woman travelling at sunset. She tells him that she lost her family and has relatives in Edo who can secure her a job as a lady-in-waiting. Minokichi offers to let her spend the night at his house with his mother. The mother takes a liking to Yuki and asks her to stay. She never leaves for Edo and Minokichi falls in love with her. The two marry and have children, living happily. The older women in the town are in awe over Yuki maintaining her youth even after having three children.

One night, Minokichi gives Yuki a set of sandals he has made. When she asks why he always gives her red ribbons on her sandals, he tells her of her youthful appearance. Yuki accepts the sandals and tries them on. She is stitching a kimono in the candlelight. In the light, Minokichi recalls the yuki-onna and sees a resemblance between them. He tells her about the strange encounter. It is then that Yuki reveals herself to be the yuki-onna, and a snowstorm comes over the home. Despite the fact he broke his word, she cannot bring herself to kill him because of her love for him and their children. Yuki then spares Minokichi and leaves on the condition that he treats their children well. As Yuki disappears into the snowstorm, a heartbroken Minokichi places her sandals outside in the snow, and after he goes back inside, Yuki takes the sandals with her.

"Hoichi the Earless"

[edit]"Hoichi the Earless" (耳無し芳一の話, Miminashi Hōichi no Hanashi) is also adapted from Hearn's Kwaidan (though it incorporates aspects of The Tale of the Heike that are mentioned, but never translated, in Hearn's book).[citation needed]

Hoichi is a young blind musician who plays the biwa. His specialty is singing the chant of The Tale of the Heike about the Battle of Dan-no-ura fought between the Taira and Minamoto clans during the last phase of the Genpei War. Hoichi is an attendant at a temple and is looked after by the others there. One night he hears a sound and decides to play his instrument in the garden courtyard. A spectral samurai appears and tells him that his lord wishes to have a performance at his house. The samurai leads Hoichi to a mysterious and ancient court. Another attendant notices that he went missing for the night as his dinner was not touched. The samurai re-appears on the next night to take Hoichi and affirms that he has not told anyone. Afterwards, the priest asks Hoichi why he goes out at night but Hoichi will not tell him. One night, Hoichi leaves in a storm and his friends follow him and discover he has been going to a graveyard and reciting the Tale of Heike to the court of the dead Emperor. Hoichi informs the court that it takes many nights to chant the entire epic. They direct him to chant the final battle - the battle of Dan-no-ura. His friends drag him home as he refuses to leave before his performance is completed.

The priest tells Hoichi he is in great danger and that this was a vast illusion from the spirits of the dead, who plan to kill Hoichi if he obeys them again. Concerned for Hoichi's safety, a priest and his acolyte write the text of the Heart Sutra on his entire body including his face to make him invisible to the ghosts and instruct him to meditate. The samurai re-appears and calls out for Hoichi, who does not answer. Hoichi's ears are visible to the samurai as they forgot to write the text on his ears. The samurai, wanting to bring back as much of Hoichi as possible, rips his ears off to show his lord his commands have been obeyed.

The next morning, the priest and the attendants see a trail of blood leading from the temple. The priest and the acolyte realize their error and believe the ears were a trade for Hoichi's life. They believe the spirits will now leave him alone. A local lord arrives at the temple with a full retinue. They have heard the story of Hoichi the earless and wish to hear him play his biwa. Hoichi is brought before the lord and says he will play to console the sorrowful spirits. The narrator states that many wealthy nobles came to the temple with large gifts of money, making Hoichi wealthy.

"In a Cup of Tea"

[edit]"In a Cup of Tea" (茶碗の中, Chawan no Naka) is adapted from Hearn's Kottō: Being Japanese Curios, with Sundry Cobwebs (1902).

Anticipating a visit from his publisher, a writer relates an old tale of an attendant of Lord Nakagawa Sadono named Sekinai. While Lord Nakagawa is on his way to make a New Year's visit, he halts with his train at a teahouse in Hakusan. While the party is resting there, Sekinai sees the face of a strange man in a cup of tea. Despite being perturbed, he drinks the cup.

Later, while Sekinai is guarding his Lord, the man whose face appeared in the tea reappears, calling himself Heinai Shikibu. Sekinai runs to tell the other attendants, but they laugh and tell him he is seeing things. Later that night at his own residence, Sekinai is visited by three ghostly attendants of Heinai Shikibu. He duels them and is nearly defeated, but the author notes the tale ends before things are resolved and suggests that he could write a complete ending, but prefers to leave the ending to the reader's imagination.

The publisher soon arrives and asks the Madame for the author, who is nowhere to be found. They both flee the scene in terror when they discover the author trapped inside a large jar of water.

Cast

[edit]

Kurokami[edit]

|

Yuki-Onna[edit]

|

Miminashi Hōichi no Hanashi[edit]

|

Chawan no naka[edit]

|

Production

[edit]While he was a student, producer Shigeru Wakatsuki, founder, and CEO of Ninjin Club, converted the idea of a film adaptation of Kwaidan: Stories and Studies of Strange Things.[7] In 1964, Toho began a three-film deal with director Masaki Kobayashi that concluded with the production of Kwaidan.[8] Kobayashi worked with composer Takemitsu Toru for six months to produce the film's score.[9] The film exhausted its budget three quarters into production, which led Kobayashi to sell his house.[9]

Release

[edit]Kwaidan premiered at the Yūrakuza Theater, the most prestigious theater in central Tokyo on December 29, 1964.[10] The roadshow version of Kwaidan was released theatrically in Japan on January 6, 1965, where it was distributed by Toho.[1] The Japanese general release for Kwaidan began on February 27, 1965.[11] Kwaidan was reedited to 125 minutes in the United States for its theatrical release which eliminated the segment "The Woman of the Snow" after the film's Los Angeles premiere.[1] It was released in the United States on July 15, 1965, where it was distributed by Continental Distributing.[1] Kwaidan was re-released theatrically in Japan on November 29, 1982, in Japan as part of Toho's 50th anniversary.[12]

Reception

[edit]This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (August 2015) |

In Japan, Yoko Mizuki won the Kinema Junpo award for Best Screenplay. It also won awards for Best Cinematography and Best Art Direction at the Mainichi Film Concours.[1] The film won international awards including Special Jury Prize at the Cannes Film Festival and was nominated for the Best Foreign Language Film at the Academy Awards.[13]

In a 1967 review, the Monthly Film Bulletin commented on the colour in the film, stating that "it is not so much that the colour in Kwaidan is ravishing...as the way Kobayashi uses it to give these stories something of the quality of a legend."[14] The review concluded that the Kwaidan was a film "whose details stay on in the mind long after one has seen it."[14] Bosley Crowther, in a 1965 New York Times review, stated that director Kobayashi "merits excited acclaim for his distinctly oriental cinematic artistry. So do the many designers and cameramen who worked with him. Kwaidan is a symphony of color and sound that is truly past compare."[15] Variety described the film as "done in measured cadence and intense feeling" and that it was "a visually impressive tour-de-force."[16]

In his review of Harakiri, Roger Ebert described Kwaidan as "an assembly of ghost stories that is among the most beautiful films I've seen".[17] Philip Kemp wrote in Sight & Sound that Kwaidan was "almost too beautiful to be scary" and that "each tale sustains its own individual mood; but all are unforgettably, hauntingly beautiful."[9]

On review aggregator Rotten Tomatoes, Kwaidan holds an approval rating of 91%, based on 46 reviews, and an average rating of 7.9/10. Its consensus reads: "Exquisitely designed and fastidiously ornate, Masaki Kobayashi's ambitious anthology operates less as a frightening example of horror and more as a meditative tribute to Japanese folklore."[18]

See also

[edit]- List of ghost films

- List of Japanese films of 1964

- List of Japanese submissions for the Academy Award for Best Foreign Language Film

- List of submissions to the 38th Academy Awards for Best Foreign Language Film

- Hoichi the Earless

References

[edit]Footnotes

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Galbraith IV 2008, p. 217.

- ^ Imamura 1987, p. 314.

- ^ Motoyama et al. 2012, p. 91.

- ^ Kinema Junpo 2012, p. 210.

- ^ "Festival de Cannes: Kwaidan". festival-cannes.com. Retrieved 2009-03-04.

- ^ "The 38th Academy Awards (1966) Nominees and Winners". oscars.org. Retrieved 2011-11-06.

- ^ Motoyama et al. 2012, p. 93.

- ^ Galbraith IV 2008, p. 451.

- ^ a b c Kemp 2020, p. 133.

- ^ Motoyama et al. 2012, p. 90.

- ^ Galbraith IV 2008, p. 218.

- ^ Galbraith IV 2008, p. 332.

- ^ Galbraith IV 2008, p. 215.

- ^ a b D.W. (1967). "Kwaidan". Monthly Film Bulletin. Vol. 34, no. 396. London: British Film Institute. pp. 135–136.

- ^ Crowther, Bosley (November 23, 1965). "Screen: 'Kwaidan,' a Trio of Subtle Horror Tales:Fine Arts Theater Has Japanese Thriller". New York Times. Archived from the original on June 9, 2016. Retrieved September 28, 2016.

- ^ Galbraith IV 1994, p. 100.

- ^ "Honor, morality, and ritual suicide". November 16, 2011. Retrieved October 2, 2022.

- ^ "KAIDAN (KWAIDAN) (GHOST STORIES) (1964) - Rotten Tomatoes". Rotten Tomatoes.com. Flixster. Retrieved 6 March 2024.

Sources

[edit]- Galbraith IV, Stuart (1994). Japanese Science Fiction, Fantasy and Horror Films. McFarland. ISBN 0-89950-853-7.

- Galbraith IV, Stuart (2008). The Toho Studios Story: A History and Complete Filmography. Scarecrow Press. ISBN 978-1461673743.

- Imamura, Shōhei (1987). Searching for Japanese Movies (in Japanese). Iwanami Shoten. ISBN 978-4000102568.

- Kemp, Phillip (2020). "Kwaidan". Sight & Sound. Vol. 30, no. 6.

- "Kinema Junpo Best Ten 85th Complete History 1924-2011". Kinema Junpo (in Japanese). May 17, 2012. ISBN 9784873767550.

- Motoyama, Sho; Matsunomoto, Kazuhiro; Asai, Kazuyasu; Suzuki, Nobutaka; Kato, Masashi (September 28, 2012). Toho Special Effects Movie Complete Works (in Japanese). villagebooks. ISBN 978-4864910132.

External links

[edit]- Kwaidan at IMDb

- ‹The template AllMovie title is being considered for deletion.› Kwaidan at AllMovie

- Kwaidan at the TCM Movie Database

- Kwaidan at Rotten Tomatoes

- "怪談 (Kaidan)" (in Japanese). Japanese Movie Database. Retrieved 2007-07-16.

- Kwaidan: No Way Out an essay by Geoffrey O’Brien at the Criterion Collection

Text of Lafcadio Hearn stories that were adapted for Kwaidan

[edit]- 1964 films

- 1964 horror films

- 1960s fantasy films

- 1960s supernatural horror films

- Cultural depictions of Minamoto no Yoshitsune

- Jidaigeki films

- Films based on short fiction

- Films directed by Masaki Kobayashi

- Films set in Kyoto

- Japanese ghost films

- Japanese horror anthology films

- Japanese fantasy films

- Folk horror films

- 1960s Japanese-language films

- Toho films

- Films scored by Toru Takemitsu

- 1960s Japanese films

- Japanese films about revenge

- Japanese supernatural horror films

- Toho tokusatsu films

- Tokusatsu films