Jerry Lewis

Jerry Lewis | |

|---|---|

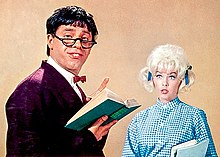

Lewis in 1957 | |

| Born | Joseph Levitch[a] March 16, 1926 Newark, New Jersey, U.S. |

| Died | August 20, 2017 (aged 91) Las Vegas, Nevada, U.S. |

| Other names |

|

| Occupations |

|

| Years active | 1931–2017[1] |

| Spouses |

|

| Children | 8, including Gary |

| Comedy career | |

| Medium |

|

| Genres |

|

| Notable works and roles | Prof. Julius F. Kelp and Buddy Love in The Nutty Professor |

| Signature | |

| |

Jerry Lewis (born Joseph Levitch;[a] March 16, 1926 – August 20, 2017) was an American comedian, filmmaker, actor, humanitarian and singer, who was famously nicknamed "The King of Comedy" and appeared in more than 59 motion pictures. These included a series of sixteen Martin and Lewis films with Dean Martin as his partner during their 10-year act in radio, stage, television and film.

He then acted without Martin in Visit to a Small Planet (1960), Cinderfella (1960), The Bellboy (1960), The Errand Boy (1961), The Ladies Man (1961), It's Only Money (1962), The Nutty Professor (1963), Who's Minding the Store? (1963), The Patsy (1964), The Disorderly Orderly (1964), The Family Jewels (1965) and Three on a Couch (1966), and portrayed Jerry Langford in Martin Scorsese's The King of Comedy (1982) earning a BAFTA Award for Best Supporting Actor nomination. He was an early and prominent user of video assist.[3]

From star of The Colgate Comedy Hour to host of The Jerry Lewis Labor Day Telethon (benefiting the Muscular Dystrophy Association), Lewis performed in concert stages, nightclubs, audio recordings and appeared in at least 117 film and television productions. He was honored with two stars on the Hollywood Walk of Fame and France awarded him the Legion of Honor in 2006.

Early life

[edit]Lewis was born on March 16, 1926, in Newark, New Jersey, to a Jewish family.[4][5] His parents were Daniel "Danny" Levitch (1902–1980), a master of ceremonies and vaudevillian who performed under the stage name Danny Lewis, whose parents immigrated to the United States from the Russian Empire to New York, and Rachael "Rae" Levitch (née Brodsky; 1904–1982), a WOR radio pianist and Danny's music director, from Warsaw.[6][7][8][9] Reports about his birth name are conflicting; in Lewis' 1982 autobiography, he claimed his birth name was Joseph, after his maternal grandfather, but his birth certificate,[10][11] the 1930 U. S. Census, and the 1940 U. S. Census all named him as Jerome.[3][9][12][13] Reports about the hospital where he was born conflict as well; biographer Shawn Levy claims Lewis was born at Clinton Private Hospital and others report it as Newark Beth Israel Hospital.[14][15][16][17] Other aspects of his early life conflict with accounts made by family members, burial records, and vital records.[citation needed]

In his teenage years, Lewis was known for pulling pranks in his neighborhood, including sneaking into kitchens to steal fried chicken and pies. He was expelled from Weequahic High School in the ninth grade and dropped out of Irvington High School in the tenth grade.[18] Lewis said that he ceased using the names Joseph and Joey as an adult to avoid being confused with Joe E. Lewis and Joe Louis.[6] By age 15, Lewis had developed his "Record Act", miming lyrics to songs while a phonograph played offstage.[19] He landed a gig at a burlesque house in Buffalo, but his performance fell flat and he was unable to book any more shows.

To make ends meet, Lewis worked as a soda jerk and a theater usher for Suzanne Pleshette's father, Gene Pleshette, at the Paramount Theatre[20] as well as at Loew's Capitol Theatre, both in New York City.[21] A veteran burlesque comedian, Max Coleman, who had worked with Lewis' father years before, persuaded him to try again. Irving Kaye,[22] a Borscht Belt comedian, saw Lewis' mime act at Brown's Hotel in Loch Sheldrake, New York, the following summer, and the audience was so enthusiastic that Kaye became Lewis' manager and guardian for Borscht Belt appearances.[23] During World War II, Lewis was rejected from military service because of a heart murmur.[24]

Career

[edit]1945–1956: Teaming with Dean Martin

[edit]

In 1945, Lewis was 19 when he met 27-year-old singer Dean Martin at the Glass Hat Club in New York City, where the two performed until they debuted at Atlantic City's 500 Club as Martin and Lewis on July 25, 1946. The duo gained attention as a double act with Martin serving as the straight man to Lewis's zany antics. The inclusion of ad-libbed improvisational segments in their planned routines added a unique quality to their act and separated them from previous comedy duos.[25]

Lewis and Martin quickly rose to national prominence, first with their popular nightclub act, then as stars of their radio program The Martin and Lewis Show.[26] The two made their television debut on CBS' Toast of the Town (later renamed as The Ed Sullivan Show) June 20, 1948.[27]

In 1950, they signed with NBC to be one of a series of weekly rotating hosts of The Colgate Comedy Hour, a live Sunday evening broadcast. Lewis, writer for the team's nightclub act, hired Norman Lear and Ed Simmons as regular writers for their Comedy Hour material.[28][29] By 1951, with an appearance at the Paramount Theatre in New York, they were a hit. The duo began their film careers at Paramount Pictures as ensemble players, in My Friend Irma (1949) and its sequel My Friend Irma Goes West (1950). Followed by their own series of 14 new movies, At War with the Army (1950), That's My Boy (1951), Sailor Beware (1952), Jumping Jacks (1952), The Stooge (1952), Scared Stiff (1953), The Caddy (1953), Money from Home (1953), Living It Up (1954), 3 Ring Circus (1954), You're Never Too Young (1955), Artists and Models (1955), Pardners (1956) and Hollywood or Bust (1956). The two appeared on the Olympic Fund Telethon and cameoed in Road to Bali (1952).

Crosby and Hope would do the same in Scared Stiff a year later. Attesting to the duo's popularity, DC Comics published The Adventures of Dean Martin and Jerry Lewis from 1952 to 1957. The team appeared on What's My Line? in 1954, the 27th annual Academy Awards in 1955, The Steve Allen Show and The Today Show in 1956.[citation needed] Martin's participation became an embarrassment in 1954 when Look magazine published a publicity photo of the team for the magazine cover but cropped Martin out.[30]

The boys did their final live nightclub act at the Copacabana on July 24, 1956. Both Lewis and Martin went on to have successful solo careers, but neither would comment on the split nor consider a reunion. Martin surprised Lewis on his appearance on The Eddie Fisher Show on September 30, 1958, appeared together at the 1959 Academy Awards closing, reunited several times publicly and sometimes privately according to interviews they gave to magazines.[citation needed]

1957–1959: Solo performances and live shows

[edit]After ending his partnership with Martin in 1956, Lewis and his wife Patty took a vacation in Las Vegas to consider the direction of his career. He felt his life was in a crisis state: "I was unable to put one foot in front of the other with any confidence. I was completely unnerved to be alone."[24] While there, he received an urgent request from his friend Sid Luft, who was Judy Garland's husband and manager, saying that she couldn't perform that night in Las Vegas because of strep throat,[24] and asking Lewis to fill in. Lewis had not sung alone on stage since he was five years old, twenty-five years before.

He delivered jokes and clowned with the audience while Garland sat off-stage, watching. He then sang a rendition of a song he had learned as a child, "Rock-a-Bye Your Baby with a Dixie Melody" along with "Come Rain or Come Shine." Lewis recalled, "When I was done, the place exploded. I walked off the stage knowing I could make it on my own."[24] At his wife's urging, Lewis used his own money to record the songs on a single.[31] Decca Records heard it, liked it and insisted he record an album for them.[32] The single of "Rock-a-Bye Your Baby" went to No. 10 and the album Jerry Lewis Just Sings went to No. 3 on the Billboard charts, staying near the top for four months and selling a million and a half copies.[24][33]

With the success of that album, he recorded additional albums More Jerry Lewis (an EP of songs from this release was released as Somebody Loves Me), and Jerry Lewis Sings Big Songs for Little People (later reissued with fewer tracks as Jerry Lewis Sings for Children). Non-album singles were released, and It All Depends On You hit the charts in April and May 1957, but peaked at only No. 68. Further singles were recorded and released by Lewis into the mid-1960s. But these were not Lewis's first forays into recording, nor his first appearance on the hit charts. During his partnership with Martin, they made several recordings together, charting at No. 22 in 1948 with the 1920s That Certain Party and later mostly re-recording songs highlighted in their films.[citation needed]

In late 1956, Lewis began performing regularly at the Sands Hotel and Casino in Las Vegas, which marked a turning point in his life and career. The Sands signed him for five years to perform six weeks each year and paid him the same amount they had paid Martin and Lewis as a team.[32] Live performances became a staple of Lewis's career and over the years he performed at casinos, theaters, and state fairs. In February 1957, Lewis followed Garland at the Palace Theater in New York and Martin called on the phone during this period to wish him the best of luck.[32] "I've never been happier", said Lewis. "I have peace of mind for the first time."[32] Lewis established himself as a solo act, starting with the first of six appearances on What's My Line? from 1956 to 1966, then guest starred on The Tennessee Ernie Ford Show, Tonight Starring Jack Paar and The Ed Sullivan Show.

In January 1957, Lewis did a number of solo specials for NBC and starred in his adaptation of "The Jazz Singer" for Startime, then hosted the Academy Awards three times, in 1956, 1957 and 1959. The third telecast, which ran twenty minutes short, forced him to improvise to fill time.[34]

Lewis remained at Paramount and started off with his first solo film The Delicate Delinquent (1957) then starred in The Sad Sack (1957). Frank Tashlin, whose background as a Looney Tunes cartoon director (for Warner Bros.) suited Lewis's brand of humor and came on board. The pair did new films, first with Rock-A-Bye Baby (1958) and then The Geisha Boy (1958). Billy Wilder asked Lewis to play the lead role of an uptight jazz musician, who winds up on the run from a mob in Some Like It Hot, but turned it down.[citation needed] Lewis then appeared in Don't Give Up The Ship (1959) and cameoed in Li'l Abner (1959).

A 1959 contract between Paramount and Jerry Lewis Productions specified a payment of $10 million plus 60% of the profits for 14 films over seven years.[35] This made Lewis the highest paid individual Hollywood talent to date and was unprecedented in that he had unlimited creative control, including final cut and the return of film rights after 30 years. Lewis's clout and box office were so strong[36] that Barney Balaban, head of production at Paramount, told the press, "If Jerry wants to burn down the studio I'll give him the match!"[37]

1960–1965: Paramount films

[edit]

Lewis ended his association with Hal Wallis, their last joint venture being Visit to a Small Planet (1960). His next film was Cinderfella (1960), directed by Frank Tashlin; it was supposed to be Lewis's summer release, but Paramount withheld it in preparation for a Christmas 1960 release. Paramount, needing a quickie movie for its summer 1960 schedule, insisted that Lewis must produce one.[38]

This resulted in Lewis's sudden transformation from movie clown to all-around filmmaker. He produced, directed, co-wrote, and starred in The Bellboy (1960). Using the Fontainebleau Hotel in Miami as his setting—on a small budget, with a very tight shooting schedule—Lewis shot the film during the day and performed at the hotel in the evenings.[38] Bill Richmond collaborated with him on many of the episodic blackouts and sight gags. The film presented a new approach for the usually frenetic and highly vocal comedian: in The Bellboy Lewis doesn't speak at all—he only whistles—until a punchline at the very end of the film.

This was really a time-saving device; by concentrating on visual action, Lewis could film the scenes faster without bothering to remember written dialogue. Another time-saver was his innovative use of instant video playback, which allowed Lewis to review each scene on videotape immediately after filming it, thus eliminating film-laboratory delays and expenses. Trade reviewer Pete Harrison noted the sight gags but felt that Lewis was not a true pantomime artist: "As a mute, there are only brief moments of his work coming close to Chaplin, Jacques Tati, or Harpo Marx. Lewis, always laughed at, fails to win the viewer's heart."[39]

Lewis later revealed that Paramount was not happy about financing a "silent movie" and withdrew backing. Lewis used his own funds to cover the movie's $950,000 budget. The Bellboy turned out to be a hit, ranking with his better successes. Variety's Gene Arneel reported independent producer Hall Bartlett's observation, "Lewis is the only star whose pictures all turn out in the black."[40]

Lewis continued to direct more films that he co-wrote with Bill Richmond, including The Ladies Man (1961), where Lewis constructed a three-story dollhouse-like set spanning two sound stages, with the set equipped with state-of-the-art lighting and sound, eliminating the need for boom microphones in each room. His next movie The Errand Boy (1961), used the same formula as The Bellboy, with Lewis turned loose in a movie studio for blackouts and sight gags.

Lewis was also somewhat active in television. NBC released him from a long-term contract in 1960; the official reason given was that Lewis was devoting more time to his motion pictures. A more probable reason was the difficulty in finding a weekly television vehicle for Lewis. (NBC did announce two series in development, "Permanent Waves" and "The Comedy Concert.")[41]

Lewis's TV appearances were usually guest shots. He appeared in The Wacky World of Jerry Lewis, Celebrity Golf, The Garry Moore Show, The Soupy Sales Show, It's Only Money (1962) and guest hosted The Tonight Show during the transition from Jack Paar to Johnny Carson in 1962, and his appearance on the show scored the highest ratings thus far in late night, surpassing other guest hosts and Paar.

The three major networks began a bidding war, wooing Lewis for his own talk show.[citation needed] Lewis then directed, co-wrote and starred in The Nutty Professor (1963). A parody of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, it featured him as Professor Kelp, a socially inept scientist who invents a serum that turns him into a handsome but obnoxious ladies' man. It is often considered to be Lewis's best film.[42][43]

In 1963, he had a cameo in It's a Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World (1963), fully starred in Who's Minding the Store? (1963) and hosted The Jerry Lewis Show, a lavish 13-week, big-budget show which aired on ABC from September to December in 1963.[citation needed] Lewis next starred in The Patsy (1964), his satire about the Hollywood star-making industry, The Disorderly Orderly (1964), his final collaboration with Tashlin, appeared in a cameo on The Joey Bishop Show and starred in The Family Jewels (1965) about a young heiress who must choose among six uncles, one of whom is up to no good and out to harm the girl's beloved bodyguard who practically raised her.[44]

In 1965, Lewis went on The David Susskind Show, starred in his final Paramount-released film Boeing Boeing (1965),[45] in which he received a Golden Globe nomination, then guest appeared on Ben Casey, The Andy Williams Show and Hullabaloo with son Gary Lewis. Lewis left Paramount in 1966, after 17 years, as the studio was undergoing a corporate shakeup, with the industrial conglomerate Gulf + Western taking over the company. Gulf + Western, scrutinizing the balance sheets, noted the diminishing box office returns of Lewis's recent pictures and did not renew his contract.

1966–1980: Columbia and other projects

[edit]

Undaunted, Lewis signed with Columbia Pictures, where he tried to reinvent himself with more serious roles[3] and starred in a string of more new box-office successes: Three on a Couch (1966), also during this period, he appeared in Way...Way Out (1966) for 20th Century-Fox, then The Big Mouth (1967), Don't Raise the Bridge, Lower the River (1968) and Hook, Line & Sinker (1969).

Lewis continued to make television appearances: The Merv Griffin Show, The Sammy Davis Jr. Show, Batman, Rowan & Martin's Laugh-In, Password, a pilot called Sheriff Who, a second version of The Jerry Lewis Show (this time as a one-hour variety show for NBC, which ran from 1967 to 1969),[46] and The Danny Thomas Hour.

He also appeared on Playboy After Dark, Jimmy Durante's The Lennon Sisters Hour, The Red Skelton Show, The Jack Benny Birthday Special, The Mike Douglas Show, The Sonny & Cher Comedy Hour, The Hollywood Palace, The Engelbert Humperdinck Show, The Irv Kupcinet Show and The Linkletter Show. Behind the scenes, he contributed to some scripts for Filmation's animated series Will the Real Jerry Lewis Please Sit Down, directed an episode of The Bold Ones[citation needed] and directed the Peter Lawford and Sammy Davis, Jr. comedy One More Time (1970), a sequel to Richard Donner's Salt and Pepper (1968).

Lewis would leave Columbia after his agreement with the studio lapsed, leaving him to produce his next movie independently. Which Way to the Front? (1970) was a World War II military comedy starring Lewis as a wealthy playboy who wants to enlist in the armed forces. Rejected, he forms his own volunteer army and infiltrates the enemy forces on the Italian front. The cast included many of Lewis's cronies, including Jan Murray, Steve Franken, Kathleen Freeman, Kenneth MacDonald, Joe Besser, and (in a broad caricature of Adolf Hitler) Sidney Miller. The film received only a limited release by Warner Bros., and was not well received by the critics or the public.

The Day the Clown Cried (1972), a drama directed by and starring Lewis and set in a Nazi concentration camp, received only brief exposure. The film was rarely discussed by him, but he said that litigation over post-production finances and copyright prevented its completion and widespread theatrical release. He also said a factor for the film's burial was that he was not proud of the effort.[47][48] It was the earliest attempt by an American film director to address the subject of The Holocaust.[49][failed verification] Following this, Lewis took a break from the movie business for several years.[50]

His television appearances during this period included Good Morning America, The Dick Cavett Show, NBC Follies, Celebrity Sportsman, Cher, Dinah!, Tony Orlando and Dawn. As Lewis continued to appear on and annually emcee his telethons, one of the most memorable was the 1976 show,[51] whereas on that broadcast, unrehearsed, Sinatra offered to bring an old friend on stage. From the wings came Dean Martin, as the audience cheered. Lewis was stunned by the surprise, but he embraced Martin and they exchanged jokes for several minutes.[52]

In 1976, producer Alexander H. Cohen signed Lewis to star in a revival of Olsen and Johnson's musical-comedy revue Hellzapoppin. "I do think that to succeed today, a comedy revue requires a larger-than-life comic", Cohen told syndicated columnist Jack O'Brian. "That is why I have engaged Jerry Lewis to star in the new production of Hellzapoppin, which I'm preparing for the coming season."[53] Cohen had revived Hellzapoppin as a TV special in 1972, and was impressed by the contributions of Lynn Redgrave; he signed her to appear opposite Lewis. This was Lewis's first Broadway show, and was so eagerly awaited that NBC-TV promised Cohen $1,000,000 for the rights to broadcast the opening night live on national television.

Out-of-town tryouts were staged in Washington, DC, Baltimore, and Boston to excellent business but mixed reviews. There was turmoil behind the scenes, as comedy star Lewis dominated the production and had serious arguments with producer Cohen, co-star Redgrave, and writer-adaptor Abe Burrows. "Lewis and Miss Redgrave had been having a much publicized feud", according to an account in the Pittsburgh Press. "He would neither rehearse nor perform any songs with her, reports said."[54] The backstage chaos extended to several sudden cast changes during the Boston run.

On January 18, 1977, NBC executives flew to Boston to see the show, and their reactions were so negative that Cohen closed the show immediately and canceled both the Broadway engagement and the TV spectacular, forfeiting the million-dollar payment from NBC. "It's not ready for Broadway and cannot be made so in three remaining weeks before the opening", Cohen said. Cohen's spokesman subsequently announced that the stars would be replaced: "Recasting means recasting, and that's it."[55]

1979–2018: Later roles and final work

[edit]Lewis went on and starred in Circus of the Stars, Pink Lady and Jeff, Hardly Working (1981, his first "comeback" film in 11 years), Late Night with David Letterman, Star Search, Cracking Up (1983, originally titled as Smorgasbord), Slapstick (Of Another Kind) (1984) and the two French movies To Catch a Cop (1984) and How Did You Get In? We Didn't See You Leave (1984), both which had their distribution under Lewis's control.[citation needed] During this period he took the very rare dramatic role as Jerry Langford in Martin Scorsese's The King of Comedy (1982), playing a late night TV talk-show host stalked by a delusional would-be comedian played by Robert De Niro.

Later, he hosted a third and final version of The Jerry Lewis Show, this time as a syndicated talk show for Metromedia, which was not continued beyond the scheduled five shows, directed an episode of Brothers, appeared at the first Comic Relief in 1986, where he was the only performer to receive a standing ovation, appeared for Classic Treasures, Fight for Life (1987),[citation needed] did a second double act with Davis Jr., hosted America's All-Time Favorite Movies and came on Speaking of Everything. While guest starring in five episodes of Wiseguy,[citation needed] its filming schedule forced Lewis to miss the Museum of the Moving Image's opening with a retrospective of his work.

Lewis then attended Martin's 72nd birthday at Bally's in Las Vegas, wheeling out a cake, sang "Happy Birthday" to him and joked, "Why we broke up, I'll never know."[56] Then starred in Cookie (1989),[57] directed episodes of Super Force in 1990 and Good Grief in 1991 and appeared in Mr. Saturday Night (1992), The Arsenio Hall Show, The Whoopi Goldberg Show, Inside The Comedy Mind, Mad About You and Arizona Dream (1993).

Then appeared for Funny Bones (1995),[58] a revival of Damn Yankees,[59][60] Inside the Actors Studio, The Martin Short Show, The Simpsons, Late Night with Conan O'Brien, Law & Order: Special Victims Unit, The Nutty Professor II (2008),[citation needed] The Talk, Max Rose (2013) The Tonight Show Starring Jimmy Fallon, The Trust (2016) and Comedians in Cars Getting Coffee.[61][62][63]

Style and reception

[edit]Comedic style

[edit]Lewis "single-handedly created a style of humor that was half anarchy, half excruciation. Even comics who never took a pratfall in their careers owe something to the self-deprecation Jerry introduced into American show business."[64]

Jerry Lewis was the most profoundly creative comedian of his generation and arguably one of the two or three most influential comedians born anywhere in this century.

The King of Comedy, 1996

His comedy style was physically uninhibited, expressive, and potentially volatile. He was known especially for his distinctive voice, facial expressions, pratfalls, and physical stunts. His improvisations and ad-libbing, especially in nightclubs and early television were revolutionary among performers. It was "marked by a raw, edgy energy that would distinguish him within the comedy landscape."[65] Will Sloan, of Flavorwire wrote, "In the late '40s and early '50s, nobody had ever seen a comedian as wild as Jerry Lewis."[66] Placed in the context of the conservative era, his antics were radical and liberating, paving the way for future comedians Steve Martin, Richard Pryor, Andy Kaufman, Paul Reubens, and Jim Carrey. Carrey wrote: "Through his comedy, Jerry would stretch the boundaries of reality so far that it was an act of anarchy ... I learned from Jerry",[67] and "I am because he was."[68]

Acting the bumbling everyman, Lewis used tightly choreographed, sophisticated sight gags, physical routines, verbal double-talk and malapropisms. "You cannot help but notice Lewis's incredible sense of control in regards to performing—they may have looked at times like the ravings of a madman but his best work had a genuine grace and finesse behind it that would put most comedic performers of any era to shame."[69] They are "choreographed as exactly as any ballet, each movement and gesture coming on natural beats and conforming to the overall rhythmic form which is headed to a spectacular finale: absolute catastrophe."[70]

Although Lewis made it no secret that he was Jewish, he was criticized for hiding his Jewish heritage. In several of his films—both with Martin and solo—Lewis's Jewish identity is hinted at in passing, and was never made a defining characteristic of his onscreen persona. Aside from the 1959 television movie The Jazz Singer and the unreleased 1972 film The Day the Clown Cried, Lewis never appeared in a film or film role that had any ties to his Jewish heritage.[4] When asked about this lack of Jewish portrayal in a 1984 interview, Lewis stated, "I never hid it, but I wouldn't announce it and I wouldn't exploit it. Plus the fact it had no room in the visual direction I was taking in my work."[5]

Lewis's physical movements in films received some criticism because he was perceived as imitating or mocking those with a physical disability.[71] Through the years, the disability that has been attached to his comedic persona has not been physical, but mental. Neuroticism and schizophrenia have been a part of Lewis's persona since his partnership with Dean Martin; however, it was in his solo career that these disabilities became important to the plots of his films and the characters. In films such as The Ladies Man (1961), The Disorderly Orderly (1964), The Patsy (1964) and Cracking Up (1983), there is either neuroticism, schizophrenia, or both that drive the plot. Lewis was able to explore and dissect the psychological side of his persona, which provided a depth to the character and the films that was not present in his previous efforts.[72]

Directorial technique

[edit]During the 1960 production of The Bellboy, Lewis pioneered the technique of using video cameras and multiple closed circuit monitors,[73] which allowed him to review his performance instantly. This was necessary since he was acting as well as directing. His techniques and methods of filmmaking, documented in his book and his USC class, enabled him to complete most of his films on time and under budget since reshoots could take place immediately instead of waiting for the dailies.[citation needed]

Man in Motion,[74] a featurette for Three on a Couch, features the video system, named "Jerry's Noisy Toy"[75] and shows Lewis receiving the Golden Light Technical Achievement award for its development. Lewis stated he worked with the head of Sony to produce the prototype. While he initiated its practice and use, and was instrumental in its development, he did not hold a patent.[76][77]

Lewis screened Spielberg's early film Amblin' and told his students, "That's what filmmaking is all about."[78] The class covered all topics related to filmmaking, including pre and post production, marketing and distribution and filming comedy with rhythm and timing.[79] His 1971 book The Total Film Maker, was based on 480 hours of his class lectures.[80] Lewis also traveled to medical schools for seminars on laughter and healing with Clifford Kuhn and also did corporate and college lectures, motivational speaking and promoted the pain-treatment company Medtronic.[citation needed]

Exposure in France

[edit]"Americans are the people who, when the French decided that Jerry Lewis was a genius, never stopped to ask why, but immediately branded France a nation of idiots." —Biographer Jeanine Basinger in Silent Stars (1999).[81]

While Lewis was popular in France for his duo films with Dean Martin and his solo comedy films, his reputation and stature increased after the Paramount contract, when he began to exert total control over all aspects of his films. His involvement in directing, writing, editing and art direction coincided with the rise of auteur theory in French intellectual film criticism and the French New Wave movement. He earned consistent praise from French critics in the influential magazines Cahiers du Cinéma and Positif, where he was hailed as an ingenious auteur.[citation needed]

His singular mise-en-scène, and skill behind the camera, were aligned with Howard Hawks, Alfred Hitchcock and Satyajit Ray. Appreciated too, was the complexity of his also being in front of the camera. The new French criticism viewed cinema as an art form unto itself, and comedy as part of this art. Lewis is then fitted into a historical context and seen as not only worthy of critique, but as an innovator and satirist of his time.[82] Jean-Pierre Coursodon states in a 1975 Film Comment article, "The merit of the French critics, auteurist excesses notwithstanding, was their willingness to look at what Lewis was doing as a filmmaker for what it was, rather than with some preconception of what film comedy should be."[83]

Not yet curricula at universities or art schools, film studies and film theory were avant-garde in early 1960s America. Mainstream movie reviewers such as Pauline Kael, were dismissive of auteur theory, and others, seeing only absurdist comedy, criticized Lewis for his ambition and "castigated him for his self-indulgence" and egotism. Despite this criticism often being held by American film critics, admiration for Lewis and his comedy continued to grow in France.[84]

Appreciation of Lewis became a misunderstood stereotype about "the French", and it was often the object of jokes in American pop culture.[85] "That Americans can't see Jerry Lewis's genius is bewildering", says N. T. Binh, a French film magazine critic. Such bewilderment was the basis of the book Why the French Love Jerry Lewis.[86]

Acting credits and accolades

[edit]

Lewis received numerous honorary awards including the Academy of Motion Pictures Arts and Sciences's Jean Hersholt Humanitarian Award in 2008, the Academy of Television Arts & Sciences' Governor's Award in 2005, and the Venice International Film Festival's Career Golden Lion in 1999. He was nominated for a Primetime Emmy Award for Best Comedian or Comedienne in 1952 and the Best Actor in a Comedy or Musical Film for his performance in Boeing, Boeing (1965). For his Broadway debut, he received a Theatre World Award nomination. Lewis was nominated for ten Golden Laurel Awards winning twice. Lewis also received a nomination for the Razzie Award for Worst Actor for his performance in Slapstick of Another Kind (1985), as well as two Stinker Award nominations for Worst Director and Worst Actor for Hardly Working (1981).[citation needed]

Charity and activism with MDA

[edit]

After meeting with Paul Cohen, founder of the Muscular Dystrophy Association (MDA), Lewis and Martin made their first appeal in early December 1951 on the finale of The Colgate Comedy Hour, followed by another in 1952. Lewis fought Rocky Marciano in a boxing bout for MDA's fund drive in 1954.[87] In 1956, the duo hosted MDA's first telethon from June 29 to June 30, before the end of their comedy act on July 25. Afterwards, the association named Lewis national chairman and helmed two Thanksgiving specials in 1957 and 1959.[88]

He would soon begin hosting and emceeing The Jerry Lewis MDA Labor Day Telethon in late 1966. Since its first broadcast on one station that year, the annual telethon aired live every Labor Day weekend for 44 years over five decades. Johnny Olson served as announcer for the first seven years, then Ed McMahon for the latter thirty-six years and Shawn Parr for Lewis's final two shows. It originated from different locations including New York, Las Vegas, Hollywood and Chicago, becoming the most watched and most successful fundraising event in the history of television.[89] Its primary songs were "Smile" (by Charlie Chaplin), "You'll Never Walk Alone" (by Rodgers and Hammerstein) and "What the World Needs Now Is Love" (by Jackie DeShannon).[citation needed]

The event [clarification needed] was the first to: raise over $1 million, in 1966;[90] be shown entirely in color, in 1967; become a networked telethon, in 1968; go coast-to-coast, in 1970; be seen outside the continental U.S., in 1972. It: raised the largest sum ever in a single event for humanitarian purposes, in 1974; had the greatest amount ever pledged to a televised charitable event, in 1980 (from the Guinness Book of World Records); was the first to be seen by 100 million people, in 1985; celebrated its 25th anniversary, in 1990; saw its highest pledge in history, in 1992; and was the first seen worldwide via internet simulcast, in 1998.[citation needed]

By 1990, societal views of disabled individuals and the telethon format had shifted. Lewis's and the telethon's methods were criticized by disabled-rights activists who believed the show was "designed to evoke pity rather than empower the disabled."[91] The activists said the telethon perpetuated prejudices and stereotypes, that Lewis treated those he claimed to be helping with little respect, and that he used offensive language when describing them.[92] Lewis rebutted the criticism and defended his methods saying, "If you don't tug at their heartstrings, then you're on the air for nothing."[93] The activist protests represented a very small minority of countless MDA patients and clients who had directly benefitted from Lewis's MDA fundraising.[citation needed]

During Lewis's lifetime, MDA-funded scientists discovered the causes of most of the diseases in the Muscular Dystrophy Association's program, developing treatments, therapies and standards of care that have allowed many people living with these diseases to live longer and grow stronger.[94] Over 200 research and treatment facilities were built with donations raised by the Jerry Lewis telethons.[citation needed] For significant and lasting contributions to the health and welfare of humanity,[citation needed] Lewis received a Nobel Peace Prize nomination, a Lifetime Achievement Award from the American Medical Association, a Governors Award and the Jean Hersholt Humanitarian Award.[95] He would host his final telethon in 2010.

On August 3, 2011, MDA announced that Lewis would no longer host its telethons[96] and that he was no longer associated with MDA. The 2011 telethon (which originally was to be Lewis's 46th and final show with MDA) featured a tribute to Lewis. In May 2015, MDA said it was discontinuing its telethon in view of "the new realities of television viewing and philanthropic giving."[97] Lewis's goal of raising "one dollar more" than the previous year's amount has been more than met almost every year, thanks to the generosity and compassion of the American public. Through his work on the telethon, Lewis has effectively led the battle to increase life expectancy and improve the quality of life for children and adults suffering from neuromuscular diseases.

In early 2016, at MDA's brand relaunch event at Carnegie Hall in New York City, Lewis broke a five-year silence during a special taped message, marking his first (and as it turned out, his final) appearance in support of MDA since his final telethon in 2010 and the end of his tenure as national chairman in 2011.[98] MDA's website states, "Jerry's love, passion and brilliance are woven throughout this organization, which he helped build from the ground up, courted sponsors for MDA, appeared at openings of MDA care and research centers, addressed meetings of civic organizations, volunteers and the MDA Board of Directors, successfully lobbied Congress for federal neuromuscular disease research funds, made countless phone calls and visits to families served by MDA.[citation needed]

Personal life

[edit]Relationships and children

[edit]Lewis wed Patti Palmer (née Esther Grace Calonico; 1921–2021), a singer with Ted Fio Rito, on October 3, 1944.[6][99][100][101][102][103] They had six sons together; five biological: Gary (born 1945),[3][104][105][106][107] Scott (born 1956), Christopher (born 1957), Anthony (born 1959) and Joseph (1964–2009);[108] and one adopted: Ronald (born 1949).[109] It was an interfaith marriage; Lewis was Jewish and Palmer was Catholic.[110]

While married to Palmer, Lewis likely fathered a daughter, Suzan (born 1952) with Lynn Dixon Kleinman.[111][112] DNA testing indicated an 88.7 percent probability that Suzan is related to Lewis' acknowledged son Gary.[113] Lewis openly pursued relationships with other women and gave unapologetic interviews about his infidelity, revealing his affairs with Marilyn Monroe and Marlene Dietrich to People in 2011.[114] Palmer filed for divorce from Lewis in 1980, after 35 years of marriage, citing Lewis's extravagant spending and infidelity on his part, and it was finalized in 1983.[115][116][117] All of Lewis's children and grandchildren from his marriage to Palmer were excluded from inheriting any part of his estate.[118][119] His eldest son, Gary, publicly called his father a "mean and evil person" and said that Lewis never showed him or his siblings any love or care.[118]

Lewis's second wife was Sandra "SanDee" Pitnick,[120] a University of North Carolina School of the Arts professionally trained ballerina and stewardess, who met Lewis after winning a bit part in a dancing scene on his film Hardly Working. They wed on February 13, 1983, in Key Biscayne, Florida,[121] adopted a daughter, Danielle (born 1992), and were married for 34 years until Lewis's death on August 20, 2017.[122][123][124]

Interests

[edit]After opening a camera shop in 1950, Lewis agreed to lend his name to "Jerry Lewis Cinemas" in 1969, offered by National Cinema Corporation, as a franchise business opportunity for those interested in theatrical movie exhibition. Jerry Lewis Cinemas stated that their theaters could be operated by a staff of as few as two with the aid of automation and support provided by the franchiser in booking film and other aspects of film exhibition. A forerunner of the smaller rooms typical of later multi-screen complexes, a Jerry Lewis Cinema was billed in franchising ads as a "mini-theatre" with a seating capacity of between 200 and 350.[citation needed]

In addition to Lewis's name, each Jerry Lewis Cinema bore a sign with a cartoon logo of Lewis in profile.[125] Initially 158 territories were franchised, with a buy-in fee of $10,000 or $15,000 depending on the territory, for what was called an "individual exhibitor." For $50,000, Jerry Lewis Cinemas offered an opportunity known as an "area directorship", in which investors controlled franchising opportunities in a territory as well as their own cinemas.[126] The success of the chain was hampered by a policy of only booking second-run, family-friendly films. Eventually the policy was changed, and the Jerry Lewis Cinemas were allowed to show more competitive movies. But after a decade the chain failed and both Lewis and National Cinema Corporation declared bankruptcy in 1980.[127]

In 1973, Lewis appeared on the 1st Annual 20-hour Highway Safety Foundation Telethon, then in 1990, wrote and directed Boy, a short film for UNICEF's How Are The Children? anthology,[128] meeting up with seven-year-old Lochie Graham in 2010, who shared his idea for "Jerry's House", a place for vulnerable and traumatized children[129][130] and in 2016, would lend his name and star power to Criss Angel's HELP (Heal Every Life Possible) charity event.[131]

Political views

[edit]Lewis kept a low political profile for many years, having taken advice reportedly given to him by President John F. Kennedy, who told him, "Don't get into anything political. Don't do that because they will usurp your energy."[132] Nevertheless, he campaigned and performed on behalf of both JFK and Robert F. Kennedy, and was a supporter of the civil rights movement. For his 1957 NBC special, Lewis held his ground when southern affiliates objected to his friendship with Sammy Davis, Jr.[citation needed] In a 1971 Movie Mirror magazine article, Lewis spoke out against the Vietnam War when his son Gary returned from service traumatized.[citation needed] He vowed to leave the country rather than send another of his sons.[citation needed]

Lewis observed that political speeches should not be at the Oscars. He stated, "I think we are the most dedicated industry in the world. And I think that we have to present ourselves that night as hard-working, caring and important people to the industry. We need to get more self-respect as an industry."[133] In a 2004 interview with The Guardian, Lewis was asked what he was least proud of, to which he answered, "Politics."[134]

He mocked citizens' lack of pride in their country, stating, "President Bush is my president. I will not say anything negative about the president of the United States. I don't do that. And I don't allow my children to do that. Likewise, when I come to England don't you do any jokes about 'Mum' to me. That is the Queen of England, you moron. Do you know how tough a job it is to be the Queen of England?"[135]

In a December 2015 interview on EWTN's World Over with Raymond Arroyo, Lewis expressed opposition to the United States letting in Syrian refugees, saying, "No one has worked harder for the human condition than I have, but they're not part of the human condition if 11 guys in that group of 10,000 are ISIS. How can I take that chance?"[136] In the same interview, he criticized President Barack Obama for not being prepared for ISIS, while expressing support for Donald Trump, saying he would make a good president because he was a good "showman." He also added that he admired Ronald Reagan's presidency.[137][138][139]

Stalking incident

[edit]In February 1994, a man named Gary Benson was revealed to have been stalking Lewis and his family.[140] Benson subsequently served four years in prison.[141]

Allegations of sexual assault

[edit]In February 2022, Vanity Fair reported that several of Lewis's co-stars from the 1960s had come forward to share allegations of sexual assault, harassment, and verbal abuse.[142][143] Those whose accounts were made public included Karen Sharpe, Hope Holiday, Anna Maria Alberghetti, and Lainie Kazan.[144]

Illness and death

[edit]Lewis suffered from a number of chronic health problems, illnesses and addictions related both to aging and a back injury sustained in a comedic pratfall. The fall has been stated as being either from a piano while performing at the Sands Hotel and Casino on the Las Vegas Strip on March 20, 1965,[145][146] or during an appearance on The Andy Williams Show.[7][147] In its aftermath, Lewis became addicted to the painkiller Percodan for thirteen years.[145] He said he had been off the drug since 1978.[146] In April 2002, Lewis had a Medtronic "Synergy" neurostimulator implanted in his back,[148] which helped reduce the discomfort. He was one of the company's leading spokesmen.[146][148]

Lewis suffered numerous heart problems throughout his life; he revealed in the 2011 documentary Method to the Madness of Jerry Lewis that he suffered his first heart attack at age 34 while filming Cinderfella in 1960.[149][150] In December 1982, at age 56, he suffered his second heart attack. Two months later, in February 1983, Lewis underwent open-heart double-bypass surgery.[151] En route to San Diego from New York City on a cross-country commercial airline flight on June 11, 2006, Lewis suffered his third heart attack at age 80.[152] It was discovered that he had pneumonia, as well as a severely damaged heart. He underwent a cardiac catheterization days after the heart attack, and two stents were inserted into one of his coronary arteries, which was 90 percent blocked.[153] The surgery resulted in increased blood flow to his heart and allowed him to continue his rebound from earlier lung problems. Having the cardiac catheterization required him to cancel several major events from his schedule, but Lewis fully recuperated in a matter of weeks.[citation needed]

In 1999, Lewis's Australian tour was cut short when he had to be hospitalized in Darwin with viral meningitis.[154][155] He was ill for more than five months. It was reported in the Australian press that he had failed to pay his medical bills. However, Lewis maintained that the payment confusion was the fault of his health insurer. The resulting negative publicity caused him to sue his insurer for US$100 million.[156]

In addition to his decades-long heart problems, Lewis had prostate cancer,[157] type 1 diabetes,[146][158] and pulmonary fibrosis.[145] In the late 1990s, Lewis was treated with prednisone[145] for pulmonary fibrosis, which caused considerable weight gain and a startling change in his appearance. In September 2001, Lewis was unable to perform at a planned London charity event at the London Palladium. He was the headlining act, and was introduced, but did not appear onstage. He had suddenly become unwell, apparently with cardiac problems.[159]

He was subsequently taken to a hospital. Some months thereafter, Lewis began an arduous, months-long therapy that weaned him off prednisone, and he lost much of the weight gained while on the drug. The treatment enabled him to return to work. On June 12, 2012, he was treated and released from a hospital after collapsing from hypoglycemia at a New York Friars Club event. This forced him to cancel a show in Sydney.[160] In an October 2016 interview with Inside Edition, Lewis acknowledged that he might not star in any more films, given his advanced age, while admitting, through tears, that he was afraid of dying, as it would leave his wife and daughter alone.[161] In June 2017, Lewis was hospitalized at a Las Vegas hospital for a urinary tract infection.[162]

Lewis died at his home in Las Vegas, Nevada, on August 20, 2017, at the age of 91.[26] The cause was end-stage cardiac disease and peripheral artery disease. Lewis was cremated.[163][164] In his will, he left his estate to his second wife of 34 years, SanDee Pitnick, and their daughter, and explicitly disinherited his children from his first marriage and their children.[165]

Controversies

[edit]In 1998, at the Aspen U.S. Comedy Arts Festival, when asked which women comics he admired, Lewis answered, "I don't like any female comedians. A woman doing comedy doesn't offend me but sets me back a bit. I, as a viewer, have trouble with it. I think of her as a producing machine that brings babies in the world."[166] He went on to praise Lucille Ball as "brilliant" and said Carol Burnett is "the greatest female entrepreneur of comedy." On other occasions, Lewis expressed admiration for female comedians Totie Fields, Phyllis Diller, Kathleen Freeman, Elayne Boosler, Whoopi Goldberg, and Tina Fey. During the 2007 MDA Telethon, Lewis used the slur "fag" in a joke, for which he apologized.[167] Lewis used the same word the following year on Australian television.[168]

Tributes and legacy

[edit]From the late 1940s to the mid-1960s, "Lewis was a major force in American popular culture."[169] Widely acknowledged as a comic genius, Lewis influenced generations of comedians, comedy writers, performers and film makers.[170] As Lewis was often referred to as the bridge from Vaudeville to modern comedy, Carl Reiner wrote after Lewis's death, "All comedians watch other comedians, and every generation of comedians going back to those who watched Jerry on the Colgate Comedy Hour were influenced by Jerry. They say that mankind goes back to the first guy ... which everyone tries to copy. In comedy that guy was Jerry Lewis."[171]

Lewis's films, especially his self-directed films, have warranted steady reappraisal. Richard Brody of The New Yorker said Lewis was "one of the most original, inventive, ... profound directors of the time" and "one of the most skilled and original comic performers, verbal and physical, ever to appear on screen."[172] Dave Kehr, a film critic and film curator for the Museum of Modern Art, wrote in The New York Times of Lewis's "fierce creativity" and "the extreme formal sophistication of his direction."[173] Kehr wrote that Lewis was "one of the great American filmmakers."[174]

As a filmmaker who insisted on the personal side of his work—who was producer, writer, director, star, and over-all boss of his productions in the interest of his artistic conception and passion—he was an auteur by temperament and in practice long before the word traveled Stateside.

The New Yorker, 2017

"Lewis was an explosive experimenter with a dazzling skill, and an audacious, innovatory flair for the technique of the cinema. He knew how to frame and present his own adrenaline-fuelled, instinctive physical comedy for the camera."[175]

Lewis was at the forefront in the transition to independent filmmaking, which came to be known as New Hollywood in the late 1960s. Writing for the Los Angeles Times in 2005, screenwriter David Weddle lauded Lewis's audacity in 1959 "daring to declare his independence from the studio system."[176] Lewis came along to a studio system in which the industry was regularly stratified between players and coaches. The studios tightly controlled the process and they wanted their people directing. Yet Lewis regularly led, often flouting the power structure to do so. Steven Zeitchik of the LA Times wrote of Lewis, "Control over material was smart business, and it was also good art. Neither the entrepreneur nor the auteur were common types among actors in mid-20th century Hollywood. But there Lewis was, at a time of strict studio control, doing both."[177]

No other comedic star, with the exceptions of Chaplin and Keaton in the silent era, dared to direct himself. "Not only would Lewis's efforts as a director pave the way for the likes of Mel Brooks and Woody Allen, but it would reveal him to be uncommonly skilled in that area as well." "Most screen comedies until that time were not especially cinematic—they tended to plop down the camera where it could best capture the action and that was it. Lewis, on the other hand, was interested in exploring the possibilities of the medium by utilizing the tools he had at his disposal in formally innovative and oftentimes hilarious ways."[178] "In Lewis's work the way the scene is photographed is an integral part of the joke. His purposeful selection of lenses, for example, expands and contracts space to generate laughs that aren't necessarily inherent in the material, and he often achieves his biggest effects via what he leaves off screen, not just visually but structurally."[179]

As a director, Lewis advanced the genre of film comedy with innovations in the areas of fragmented narrative, experimental use of music and sound technology, and near surrealist use of color and art direction.[3][180][181] This prompted his peer, filmmaker Jean Luc Godard to proclaim, "Jerry Lewis ... is the only one in Hollywood doing something different, the only one who isn't falling in with the established categories, the norms, the principles. ... Lewis is the only one today who's making courageous films. He's been able to do it because of his personal genius."[182] Jim Hemphill for American Cinematheque wrote, "They are films of ambitious visual and narrative experimentation, provocative and sometimes conflicted commentaries on masculinity in post-war America, and unsettling self-critiques and analyses of the performer's neuroses."[citation needed]

Intensely personal and original, Lewis's films were groundbreaking in their use of dark humor for psychological exploration.[183] Justin Chang of the Los Angeles Times said, "The idea of comedians getting under the skin and tapping into their deepest, darkest selves is no longer especially novel, but it was far from a universally accepted notion when Lewis first took the spotlight. Few comedians before him had so brazenly turned arrested development into art, or held up such a warped fun house mirror to American identity in its loudest, ugliest, vulgarest excesses. Fewer still had advanced the still-radical notion that comedy doesn't always have to be funny, just fearless, in order to strike a nerve."[184]

Before 1960, Hollywood comedies were screwball or farce. Lewis, from his earliest 'home movies, such as How to Smuggle a Hernia Across the Border, made in his playhouse in the early 1950s, was one of the first to introduce satire as a full-length film. This "sharp-eyed" satire continued in his mature work, commenting on the cult of celebrity, the machinery of 'fame', and "the dilemma of being true to oneself while also fitting into polite society." Stephen Dalton in The Hollywood Reporter wrote, Lewis had "an agreeably bitter streak, offering self-lacerating insights into celebrity culture which now look strikingly modern. Even post-modern in places." Speaking of The King of Comedy, "More contemporary satirists like Garry Shandling, Steve Coogan and Ricky Gervais owe at least some of their self-deconstructing chops to Lewis's generously unappetizing turn in Scorsese's cult classic."[185]

Lewis was an early master of deconstruction to enhance comedy. From the first Comedy Hours he exposed the artifice of on-stage performance by acknowledging the lens, sets, malfunctioning props, failed jokes, and tricks of production. As Jonathan Rosenbaum wrote: Lewis had "the impulse to deconstruct and even demolish the fictional "givens" of any particular sketch, including those that he might have dreamed up himself, a kind of perpetual auto-destruction that becomes an essential part of his filmmaking as he steadily gains more control over the writing and direction of his features."[186] His self directed films abound in behind-the-scene reveals, demystifying movie-making. Daniel Fairfax writes in Deconstructing Jerry: Lewis as a Director, "Lewis deconstructs the very functioning of the joke itself." ... quoting Chris Fujiwara, "The Patsy is a film so radical that it makes comedy out of the situation of a comedian who isn't funny."[187] The final scene of The Patsy is famous for revealing to the audience the movie as a movie, and Lewis as actor/director.[188] Lewis wrote in The Total Filmmaker, his belief in breaking the fourth wall, actors looking directly into the camera, despite industry norms.[189]

Robert De Niro and Sandra Bernhard, both of whom starred with Lewis in The King of Comedy, reflected on his death. Bernhard said: "It was one of the great experiences of my career, he was tough but one of a kind." De Niro said: "Jerry was a pioneer in comedy and film. And he was a friend. I was fortunate to have seen him a few times over the past couple of years. Even at 91, he didn't miss a beat ... or a punchline. You'll be missed."[190] There was also a New York Friars Club roast in honor of Lewis with Sarah Silverman and Amy Schumer.[191][192][193][194] Martin Scorsese recalls working with him on The King of Comedy, "It was like watching a virtuoso pianist at the keyboard."[195][196][197][198][199][200][201][202] Lewis was the subject of a documentary Jerry Lewis: Method to the Madness.[203][204][205][206][207][208][209]

Peter Chelsom, director of Funny Bones wrote, "Working with him was a masterclass in comic acting – and in charm. From the outset he was generous." "There's a very thin line between a talent for being funny and being a great actor. Jerry Lewis epitomized that. Jerry embodied the term "funny bones": a way of differentiating between comedians who tell funny and those who are funny."[210] Director Daniel Noah recalling his relationship with Lewis during production of Max Rose wrote, "He was kind and loving and patient and limitlessly generous with his genius. He was unbelievably complicated and shockingly self-aware."[211]

Actor and comedian Jeffrey Tambor wrote after Lewis's death, "You invented the whole thing. Thank you doesn't even get close."[212]

Actor and comedian Jim Carrey tweeted after Lewis's death, "I am because he was."[213]

There have been numerous retrospectives of Lewis's films in the U.S. and abroad, most notably Jerry Lewis: A Film and Television Retrospective at Museum of the Moving Image, the 2013 Viennale, the 2016 Melbourne International Film Festival, The Innovator: Jerry Lewis at Paramount at American Cinematheque in Los Angeles, Happy Birthday Mr. Lewis: The Kid Turns 90 at MoMA in New York City,[214] and "Jerry Lewis, cinéaste" at the French Cinémathèque in 2023.[215]

In 2017, Lewis with others inaugurated and founded Legionnaires of Laughter and Legacy Awards, and the first Legacy Award held in Downtown, New York.[216] On August 21, 2017, multiple hotel marquees on the Las Vegas Strip honored Lewis with a coordinated video display of images of his career as a Las Vegas performer and resident.[217]

In popular culture

[edit]Between 1952 and 1957, DC Comics published a 40-issue comic book series with Martin & Lewis as the main protagonists, titled The Adventures of Dean Martin and Jerry Lewis.[218] They continued the series under the new title The Adventures of Jerry Lewis after the team slit up, running until issue #124 in 1971.[219]

In The Simpsons, the character of Professor Frink is based on Lewis's Julius Kelp from The Nutty Professor.[220] Lewis himself would later voice the character's father in the episode "Treehouse of Horror XIV." In Animaniacs, Lewis is parodied in the form of a recurring character named Mr. Director (voiced by series writer Paul Rugg), who initially appears as a comedy director whose appearance and mannerisms are based around those of Lewis, complete with frequent exclamations of faux-Yiddish. While he is typically depicted as a caricature of Lewis, on some occasions Mr. Director has also been seen as a caricature of Marlon Brando and as a birthday clown, although still retaining the voice and mannerisms inspired by Lewis.

In Family Guy, Peter recreates Lewis's 'chairman of the board' scene from The Errand Boy. Comedian, actor and friend of Lewis, Martin Short, satirized him on the series SCTV in the sketches "The Nutty Lab Assistant", "Martin Scorsese presents Jerry Lewis Live on the Champs Elysees!", "The Tender Fella", and "Scenes From an Idiots Marriage",[221][222][223] as well as on Saturday Night Live's "Celebrity Jeopardy!."[224] Also on SNL, the Martin and Lewis reunion on the 1976 MDA Telethon is reported by Chevy Chase on Weekend Update.[225] Comedians Eddie Murphy and Joe Piscopo both parodied Lewis when he hosted SNL in 1983. Piscopo also channeled Jerry Lewis while performing as a 20th-century stand-up comedian in Star Trek: The Next Generation; in the second-season episode "The Outrageous Okona", Piscopo's Holodeck character, The Comic, tutors android Lieutenant Commander Data on humor and comedy.[226] Comedian and actor Jim Carrey satirized Lewis on In Living Color in the sketch "Jheri's Kids Telethon."[227] Carrey had an uncredited cameo playing Lewis in the series Buffalo Bill on the episode "Jerry Lewis Week."[228] He also played Lewis, with impersonator Rich Little as Dean Martin, on stage. Actor Sean Hayes portrayed Lewis in the made-for-TV movie Martin and Lewis, with Jeremy Northam as Dean Martin.[229] Actor Kevin Bacon plays the Lewis character in the 2005 film Where The Truth Lies, based on a fictionalized version of Martin and Lewis.[230] In the satiric novel, Funny Men, about singer/wild comic double act, the character Sigmund "Ziggy" Blissman, is based on Lewis.[citation needed]

John Saleeby, writer for National Lampoon has a humor piece "Ten Things You Should Know About Jerry Lewis."[231] In the animated cartoon Popeye's 20th Anniversary, Martin and Lewis are portrayed on the dais.[232] The animated series Animaniacs satirized Lewis in several episodes. The voice and boyish, naive cartoon character SpongeBob SquarePants is partially based on Lewis, with particular inspiration from his film The Bellboy.[233][234] In 1998, The MTV animated show Celebrity Deathmatch had a clay-animated fight to the death between Dean Martin and Lewis. In a 1975 re-issue of MAD Magazine the contents of Lewis's wallet is satirized in their on-going feature "Celebrities' Wallets."[citation needed]

Lewis, and Martin & Lewis, as himself or his films, have been referenced by directors and performers of differing genres spanning decades, including Andy Warhol's Soap Opera (1964), John Frankenheimer's I Walk the Line (1970), Francis Ford Coppola's The Godfather (1972), Randal Kleiser's Grease (1978), Rainer Werner Fassbinder's In a Year of 13 Moons (1978), Robert Zemeckis's Back to the Future (1985), Quentin Tarantino's Four Rooms (1995), Quentin Tarantino's Pulp Fiction (1994), Martin Scorsese's Gangs of New York (2002), Hitchcock (2012), Ben Stiller's The Secret Life of Walter Mitty (2013), Jay Roach's Trumbo (2015), The Comedians (2015), Baskets (2016), The Sopranos (1999), Seinfeld (1996, 1998), and The Marvelous Mrs. Maisel (2017, 2018).[citation needed]

Similarly, varied musicians have mentioned Lewis in song lyrics including, Ice Cube, The Dead Milkmen, Queen Latifah, and Frank Zappa.[235] The hip hop music band Beastie Boys have an unreleased single "The Jerry Lewis", which they mention, and danced to, on stage in Asheville, North Carolina in 2009.[236] In their film Paul's Boutique—A Visual Companion, clips from The Nutty Professor play to "The Sounds of Science".[237]

Apple iOS 10 includes an auto-text emoji for 'professor' with a Lewis lookalike portrayal from The Nutty Professor.[238] The word "flaaaven!", with its many variations and rhymes, is a Lewis-ism often used as a misspoken word or a person's mis-pronounced name.[239] In a 2016 episode of the podcast West Wing Weekly, Joshua Malina is heard saying "flaven" when trying to remember a character's correct last name. Lewis's signature catchphrase "Hey, Laaady!" is ubiquitously used by comedians and laypersons alike.[240]

Sammy Petrillo bore a coincidental resemblance to Lewis,[241][242] so much so that Lewis at first tried to catch and kill Petrillo's career by signing him to a talent contract and then not giving him any work. When that failed (as Petrillo was under 18 at the time), Lewis tried to blackball Petrillo by pressuring television outlets and then nightclubs,[243] also threatening legal action after Petrillo used his Lewis impersonation in the film Bela Lugosi Meets a Brooklyn Gorilla.[244]

Over the years, countless actors and performers have regularly impersonated or portrayed Lewis in various tribute shows, most notably Nicholas Arnold, Tony Lewis, David Wolf, and Matt Macis.[245][246][247][248]

Bibliography

[edit]

- Lewis, Jerry (1962). Instruction Book For ..."Being a Person" or (Just Feeling Better). Self-published. ISBN 978-0-937-539743. (ISBN is for the 2004 Mass Market Edition)

- Lewis, Jerry (1971). The Total Film-Maker. New York City: Random House. ISBN 978-0-394-46757-3.

- Lewis, Jerry; Gluck, Herb (1982). Jerry Lewis: In Person. New York: Atheneum. ISBN 978-0-689-11290-4.

- Lewis, Jerry; Kaplan, James (2005). Dean & Me (A Love Story). New York: Doubleday. ISBN 978-0-7679-2086-5.

Biography

[edit]- Levy, Shawn (1997). King of Comedy: The Life and Art of Jerry Lewis. Archived May 30, 2023, at the Wayback Machine New York: St. Martin's Press. ISBN 9781250122605

Documentaries

[edit]- Annett Wolf (Director) (1972) The World of Jerry Lewis (unreleased)

- Robert Benayoun (Director) (1982) Bonjour Monsieur Lewis (Hello Mr. Lewis)

- Burt Kearns (Director) (1989) Telethon (Released in US, 2014)

- Carole Langer (Director) (1996) Jerry Lewis: The Last American Clown

- Eckhart Schmidt (Director) (2006) König der Komödianten (King of Comedy)*

- Gregg Barson (Director) (2011). Method to the Madness of Jerry Lewis

- Gregory Monro (Director) (2016). Jerry Lewis: The Man Behind the Clown (Motion picture).

Notes

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Hirschberg, Lynn (October 28, 1982). "What's So Funny About Jerry Lewis?". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on October 11, 2018. Retrieved October 11, 2018.

- ^ Kehr, Dave (August 20, 2017). "Jerry Lewis, mercurial comedian and filmmaker, dies at 91". The New York Times. Archived from the original on June 27, 2019. Retrieved August 20, 2017.

Most sources, including his 1982 autobiography, Jerry Lewis: In Person, give his birth name as Joseph Levitch. But Shawn Levy, author of the exhaustive 1996 biography King of Comedy: The Life and Art of Jerry Lewis, unearthed a birth record that gave his first name as Jerome.

- ^ a b c d e Kehr, Dave (August 30, 2017). "Jerry Lewis, a Jester Both Silly and Stormy, Dies at 91 (correction)". The New York Times. Archived from the original on June 27, 2019. Retrieved October 11, 2022.

- ^ a b Dale, Alan (2000). Comedy is a Man in Trouble. University of Minnesota Press. ISBN 9780816636570. JSTOR 10.5749/j.cttts86x.

- ^ a b "My 1984 interview with Jerry Lewis – The Bad and the Beautiful". Archived from the original on June 29, 2020. Retrieved June 29, 2020.

- ^ a b c Sources:

- Lewis, Jerry; Gluck, Herb (1982). Jerry Lewis: In Person. New York: Atheneum. ISBN 978-0-689-11290-4.

- Jerry Lewis ... The Last American Clown.

90-minute documentary, 1996, narrated by Alan King

- ^ a b "Jerry Lewis on Dean Martin: 'A Love Story'". NPR. October 25, 2005. Archived from the original on June 30, 2022. Retrieved June 16, 2009. (online excerpt from book, with link to Jerry Lewis. "Interview". Fresh Air (Interview). Interviewed by Terry Gross.

- ^ Sources:

- "Jerry Lewis". Encyclopædia Britannica. Archived from the original on February 13, 2010. Retrieved June 26, 2010.

- "Jerry Lewis Biography". Future now films. Archived from the original on June 19, 2017. Retrieved January 2, 2017.

- "Jerry Lewis Film Reference bio". Filmreference.com. Archived from the original on June 16, 2017. Retrieved October 23, 2011.

- ^ a b United States Census, 1940", database with images, FamilySearch (March 15, 2018) Archived April 4, 2023, at the Wayback Machine, Rae Lewis in household of Daniel Lewis, Ward 2, Irvington, Irvington Town, Essex, New Jersey, United States; citing enumeration district (ED) 7-174B, sheet 4B, line 49, family 95, Sixteenth Census of the United States, 1940, NARA digital publication T627. Records of the Bureau of the Census, 1790–2007, RG 29. Washington, DC: National Archives and Records Administration, 2012, roll 2334.

- ^ Sragow, Michael (June 9, 1996). "Funny Bones". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on July 8, 2019. Retrieved July 8, 2019.

- ^ Levy, Shawn (1997). King of Comedy: The Life and Art of Jerry Lewis. St. Martin's Press. ISBN 978-0312168780.[page needed]

- ^ "United States Census, 1930", database with images, FamilySearch (accessed July 3, 2019)[permanent dead link], Daniel Lewis, Newark (Districts 1–250), Essex, New Jersey, United States; citing enumeration district (ED) ED 149, sheet 13A, line 16, family 321, NARA microfilm publication T626 (Washington D.C.: National Archives and Records Administration, 2002), roll 1337; FHL microfilm 2,341,072.

- ^ Tugend, Tom (August 23, 2017). "Obituary: Jerry Lewis, comedian and filmmaker, dies at 91". Jewish Journal. Archived from the original on February 7, 2019. Retrieved February 4, 2019.

- ^ "Jerry Lewis' Early Years". Neatorama. August 30, 2017. Archived from the original on July 5, 2019. Retrieved July 5, 2019.

- ^ Levy, Shawn (1997). King of Comedy: The Life and Art Of Jerry Lewis. St. Martin's Press. ISBN 978-0312168780.[page needed]

- ^ Wiener, Robert. "Newark natives recall antics of Jerry Lewis". njjewishnews.timesofisrael.com. Archived from the original on July 5, 2019. Retrieved July 5, 2019.

- ^ Wiener, Robert. "'The Beth' marks 110 years as Newark landmark". njjewishnews.timesofisrael.com. Archived from the original on July 5, 2019. Retrieved July 5, 2019.

- ^ Wiener, Robert. "Newark natives recall antics of Jerry Lewis". njjewishnews.timesofisrael.com. Archived from the original on July 5, 2019. Retrieved April 14, 2023.

- ^ Denoff, Sam (October 27, 2000). Jerry Lewis Interview Part 1 of 5 – TelevisionAcademy.com/Interviews. Academy of Television Arts & Sciences Foundation (Interview). Event occurs at 13:28. Archived from the original on June 24, 2021. Retrieved February 15, 2021.

- ^ Sources:

- Abramson, Stephen J. (February 9, 2006). Suzanne Pleshette Interview Part 1 of 5 – TelevisionAcademy.com/Interviews. Academy of Television Arts & Sciences Foundation (Interview). Archived from the original on June 24, 2021. Retrieved February 15, 2021.

- Abramson, Stephen J. (February 9, 2006). Suzanne Pleshette Interview Part 2 of 5 – TelevisionAcademy.com/Interviews. Academy of Television Arts & Sciences Foundation (Interview). Archived from the original on June 24, 2021. Retrieved February 15, 2021.

- Abramson, Stephen J. (February 9, 2006). Suzanne Pleshette Interview Part 3 of 5 – TelevisionAcademy.com/Interviews. Academy of Television Arts & Sciences Foundation (Interview). Archived from the original on June 24, 2021. Retrieved February 15, 2021.

- Abramson, Stephen J. (February 9, 2006). Suzanne Pleshette Interview Part 4 of 5 – TelevisionAcademy.com/Interviews. Academy of Television Arts & Sciences Foundation (Interview). Archived from the original on June 24, 2021. Retrieved February 15, 2021.

- Abramson, Stephen J. (February 9, 2006). Suzanne Pleshette Interview Part 5 of 5 – TelevisionAcademy.com/Interviews. Academy of Television Arts & Sciences Foundation (Interview). Archived from the original on June 24, 2021. Retrieved February 15, 2021.

- ^ "A 'Gala Closing' For Loew's Capitol". Variety. April 24, 1968. p. 5.

- ^ Sources:

- "Jerry Lewis facts, information, pictures – Encyclopedia.com articles about Jerry Lewis". Encyclopedia. Archived from the original on December 29, 2017. Retrieved December 17, 2017.

- "Just Sings". Album liner notes.[permanent dead link]

- Levy, Shawn (May 10, 2016). King of Comedy: The Life and Art Of Jerry Lewis. St. Martin's Press. ISBN 9781250122605 – via Google Books.

- "Did you know". Shutan. Archived from the original on October 24, 2017. Retrieved December 17, 2017.

- ^ "Jerry Lewis". Patterson & associates. Archived from the original on December 29, 2017. Retrieved December 17, 2017.

- ^ a b c d e Lewis, Jerry (2006). Dean and Me. Three Rivers Press. p. 173. ISBN 978-0-76792087-2.

- ^ "Jerry Lewis and Dean Martin: Inside the Beloved Comedy Duo's Bitter Split and Long-Awaited Reunion". PEOPLE.com. Archived from the original on March 19, 2021. Retrieved September 2, 2020.

- ^ a b Natale, Richard; Dagan, Carmel (August 20, 2017). "Jerry Lewis, Comedy Legend, Dies at 91". Variety. ISSN 0042-2738. Archived from the original on August 12, 2019. Retrieved December 13, 2017.

- ^ McKenzie, Joi-Marie (August 20, 2017). "Comedy icon Jerry Lewis dies at 91". ABC News. Archived from the original on August 20, 2017. Retrieved August 20, 2017.

- ^ Gray, Tim (October 30, 2015). "Norman Lear Looks Back on Early Days as TV Comedy Writer". Archived from the original on February 6, 2018. Retrieved December 13, 2017.

- ^ "52G to Simmons, Lear to do five Martin-Lewis TV shows". Billboard. October 31, 1953 – via Google Books.

- ^ Clark, Mike (October 25, 2005). "'Dean & Me' really is a love story". usatoday.com. Archived from the original on August 2, 2013. Retrieved January 15, 2013.

- ^ "Image of record cover for Jerry Lewis single recording of "Rock-A-Bye Baby"". Archived from the original on August 21, 2017. Retrieved April 16, 2017.

- ^ a b c d "Jerry Lewis 'Goes Over' in a Big Way", The Star Press (Muncie, Indiana), December 2, 1956, p. 23

- ^ Lewis, Jerry. "Rock-a-Bye helps Jerry Lewis become a singer" Archived January 3, 2017, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ 1959 Academy Awards (1959). "Jerry Lewis Ad Libs at the Oscars". The Oscars. Archived from the original on December 11, 2021 – via YouTube.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Krutnik, Frank (2000). Inventing Jerry Lewis. Smithsonian Institution Press. p. 105. ISBN 978-1560983699.

- ^ "Jerry Lewis' Foreseeable $10-Mil From Paramount During Next 7 Years". Variety. June 10, 1959. p. 28. Retrieved June 15, 2019 – via Archive.org.

- ^ Moffitt, Sam (January 20, 2014). "Method to The Maddess of Jerry Lewis the DVD Review". wearemoviegeeks.com. Archived from the original on March 2, 2018. Retrieved March 1, 2018.

- ^ a b "Jerry Lewis, Nonpareil Genius of Comedy, Dies at 91". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on May 11, 2020. Retrieved August 20, 2017.

- ^ Pete Harrison, Harrison's Reports, July 20, 1960, p. 119.

- ^ Gene Arneel, "Down to a Slapstick Single—And All Lewis Pix B.O. Clix", Variety, Sept. 7, 1960, p. 3.

- ^ NBC press release, Aug. 25, 1960.

- ^ Jones, Kenneth. "Producers of Nutty Professor Hope to Earn Broadway Tenure for New Marvin Hamlisch-Rupert Holmes Show", Playbill, August 17, 2012, accessed August 19, 2013

- ^ Ng, David (August 2, 2012). "Jerry Lewis' Nutty Professor' musical opens in Nashville". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved August 18, 2013.

- ^ "The Family Jewels (1965) • Senses of Cinema". sensesofcinema.com. Archived from the original on February 27, 2018. Retrieved February 26, 2018.

- ^ "Breaking News: Jerry Lewis Dies at 91". BroadwayWorld.com. Archived from the original on August 21, 2017. Retrieved August 20, 2017.

- ^ McLellan, Dennis. "Iconic comedian Jerry Lewis dies at 91". chicagotribune.com. Archived from the original on August 20, 2017. Retrieved August 20, 2017.

- ^ Handy, Bruce (August 21, 2017). "The French Film Critic Who Saw Jerry Lewis's Infamous Holocaust Movie—and Loved It". Vanity Fair. Archived from the original on February 4, 2023. Retrieved November 26, 2023.

- ^ "Clown: teaser for unfinished Jerry Lewis Documentary". tracesfilm. September 6, 2016. Archived from the original on December 11, 2021 – via YouTube.

- ^ Brody, Richard (August 20, 2017). "Postscript: Jerry Lewis". New Yorker. Archived from the original on February 19, 2023. Retrieved February 9, 2018.

- ^ "Repelling Rejection, or: The Disappearance of Jerry Lewis, and Some Side-Effects". www.lolajournal.com. Archived from the original on June 7, 2023. Retrieved December 12, 2023.

- ^ Liebenson, Donald (September 2016). "When Jerry Met Dean-Again, on Live Television". Vanity Fair. Archived from the original on June 10, 2017. Retrieved March 30, 2018.

- ^ "23 August 1977". drowsyvenus. Archived from the original on November 9, 2019 – via YouTube.

- ^ Alexander H. Cohen to Jack O'Brian, Paterson News, Paterson, NJ, Aug. 9, 1976, p. 19.

- ^ Pittsburgh Press, Jan. 24, 1977, p. A-8.

- ^ Dan Lewis, "It's curtains for 'Hellzapoppin'", The Record, Hackensack, NJ, Jan. 20, 1977, p. 28.

- ^ Lewis, Jerry; Kaplan, James (October 23, 2005). "'We Had That X Factor' (Dean Martin and Jerry Lewis)". Parade. Archived from the original on March 22, 2006. Retrieved November 7, 2008.

- ^ Barnes, Mike; Byrge, Duane (August 20, 2017). "Jerry Lewis, Nonpareil Genius of Comedy, Dies at 91". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on May 13, 2021. Retrieved September 4, 2024.

- ^ Levy, Shawn. "Dem Bones". Film Comment. No. May/June 1995. pp. 2–3, 7.

- ^ Canby, Vincent (March 13, 1995). "Theater Review: Damn Yankees; Finally, Jerry Lewis Is on Broadway". The New York Times. Archived from the original on August 22, 2017. Retrieved August 22, 2017.

- ^ Byrge, Duane; Barnes, Mike (August 20, 2017). "Jerry Lewis Nonpareil Genius of Comedy Dead at 91". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on May 11, 2020. Retrieved March 2, 2018.

- ^ McNary, Dave (May 15, 2009). "Jerry Lewis To Star In 'Max Rose'". Variety. Archived from the original on December 15, 2009. Retrieved June 15, 2009.

- ^ Lewis, Andy (December 19, 2016). "Watch the Most Painfully Awkward Interview of 2016: 7 Minutes with Jerry Lewis". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on December 17, 2017. Retrieved December 16, 2017.

- ^ "Jerry Lewis To Honor Robin Williams At Legionnaires Of Laughter Awards". Look to the Stars. May 22, 2017. Archived from the original on October 4, 2020. Retrieved August 25, 2020.

- ^ Mclellen, Dennis (August 20, 2017). "The Slapstick, The Telethons, The Laaady!". LA Times. Archived from the original on April 17, 2020. Retrieved April 16, 2020.

- ^ Romano, Aja (August 20, 2017). "Jerry Lewis, Legendary Standup, Actor-Director, and comedy Misanthrope, is Dead at 91". vox.com. Archived from the original on February 21, 2018. Retrieved February 21, 2018.

- ^ Sloan, Will (March 1, 2016). "Pure Unfiltered Id Reappraising Jerry Lewis". Flavorwire. Archived from the original on February 6, 2018. Retrieved February 6, 2018.

- ^ Carrey, Jim (August 23, 2017). "He Is Part of My Makeup. Jim Carrey on What He Learned From Jerry Lewis". Time. Archived from the original on December 27, 2017. Retrieved February 5, 2018.

- ^ Kreps, Daniel (August 20, 2017). "Jerry Lewis: Martin Scorsese, Jim Carrey, More Remember Comedy Legend". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on February 6, 2018. Retrieved February 5, 2018.

- ^ Sobczynski, Peter (August 22, 2017). "An American Original The RogerEbert.com Staff Remembers Jerry Lewis". rogerebert.com. Archived from the original on February 11, 2018. Retrieved February 10, 2018.